This summer, for the first time, a report has considered the impact of two of the most severe threats to the global environment — climate change and biodiversity loss.

The Secretariat of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change published a joint report on the two issues in July.

“I think there’s this symbolic importance in here that it really has provided a mark, a milestone, that (in) the plan for climate mitigations and biodiversity conservation, they will need to think about the other aspect,” said William Cheung, director and professor at the Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries at the University of British Columbia and a participant in the joint IPBES and IPCC workshop.

“Let’s have all hands on deck now, because I think there are reports after reports that we cannot just read anymore.”

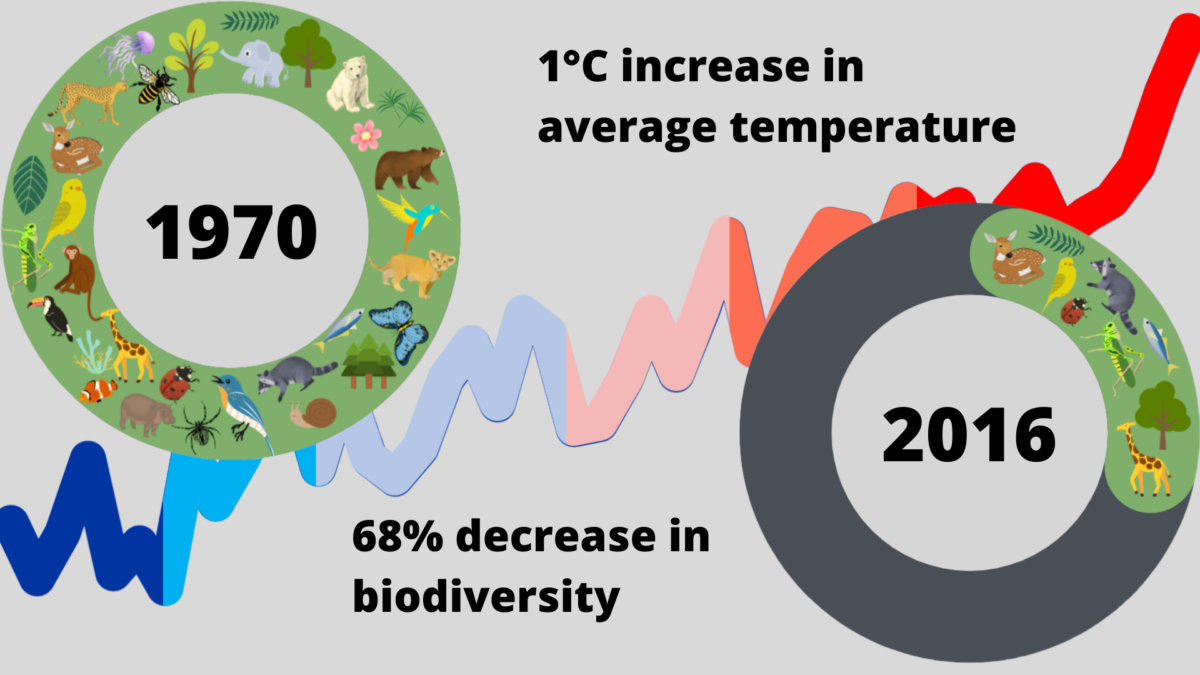

According to the World Wildlife Fund’s Living Planet Index, 2020, global biodiversity decreased 68 per cent between 1970 and 2016. Latin America and the Caribbean have fared the worst with an average decline of 94 per cent.

In the same 46-year time frame, the average global temperature has increased by about 1 C, according to NASA’s Global Land Ocean Temperature Index.

While species extinction and global temperature are only two defining characteristics of these environmental problems, they show a correlation between the two major crises.

In fact, climate change is one of the five direct drivers of biodiversity loss identified by the IPBES.

Cheung said it is important to note that biodiversity loss can also drive climate change. For example, many plant species take in carbon dioxide. If their populations diminish, there will be more CO2 in the atmosphere contributing to the greenhouse effect.

But it is not only the issues that propel each other. Sometimes solutions to one problem hinder work on the other.

For example, deforestation is a known driver of climate change and thus reforestation is often seen as a solution. However, if these forests are not regenerated with original tree species, other native populations will not return.

“It can actually have negative impacts on biodiversity,” Cheung said.

Michael Drescher, an associate professor of the School of Planning at the University of Waterloo, said animals can only move so far to adapt to new climatic conditions.

He used the example of climbing a mountain to reach higher altitudes and lower temperatures.

“Habitats can of course move up only so far,” he said. “And then they are at the peak of a mountain potentially. And then there’s nowhere to go. And then these habitats get lost.”

He also noted that plants can’t move quickly to a new location.

“I remember driving with a car on the highway in the summer, and the windshield was just covered with dead insects in the drive on the highway, he said. “Today, that doesn’t happen anymore because we just lost so many insects, they’re just not there anymore.

Michael Drescher, associate professor of the School of Planning at the University of Waterloo

Anyone who has read or watched the news can see climate change happening in front of their own eyes.

Wildfires, flooding and heatwaves are just a few examples of extreme environmental events tormenting the globe.

“Those are warning signs … (of) that big need to act now and that we need to pay attention to existing policy discussions that are happening for climate change,” said Cheung.

However, biodiversity loss is often overlooked because it is harder to see, said Drescher.

“I remember driving with a car on the highway in the summer, and the windshield was just covered with dead insects in the drive on the highway, he said. “Today, that doesn’t happen anymore because we just lost so many insects, they’re just not there anymore. It doesn’t mean that the species necessarily have gone extinct. Yet, we have just lost massively, the abundance of insects.”

Drescher suspects that one of the reasons people find these issues hard to understand is because of what is called a shifting reference. When people think about climate change, they don’t compare the present to 50 or 100 years ago. They compare it to five years ago and the change doesn’t seem so drastic.

“That’s a psycho psychological effect,” he said. “And that makes it difficult for the general population to understand how drastic changes really are that we have been going through.”

“If you’re in a house, and on the one hand, your house is on fire. And on the other hand, it is also engulfed by a flood. What are you going to do? Are you going to deal just with a flood or just with a fire? You have to deal with both at the same time because either one could kill you.”

MICHAEL DRESCHER, ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF THE SCHOOL OF PLANNING AT THE UNIVERSITY OF WATERLOO

The report from the IPBES and IPCC was the first joint report on the issues of climate change and biodiversity loss and yet scientists have known for a long time that the problems are interconnected.

“There are different types of interactions, such as trade-offs and co-benefits,” said Cheung. “That’s important for policymakers to consider, otherwise, we may design a policy that would only do one job, that will not help either. And it will actually negatively affect you.”

Drescher said the issues are often looked at separately because each is so large in scope.

“I think it’s each one of these questions is so complex and so difficult. Dealing with that issue in itself is already an enormous challenge, then having to deal with both at the same time, it’s just at least appears exponentially more difficult than any one of those issues by itself,” he said. “I think for a long time, people, including policymakers like to weaken the war, the information that was produced by scientists, certainly for 30 years, if not less. And it still needs to really come home in people’s awareness that these are issues.”

Nevertheless, he stressed the importance of tackling both issues in tandem.

“If you’re in a house, and on the one hand, your house is on fire. And on the other hand, it is also engulfed by a flood. What are you going to do?” he said. “Are you going to deal just with a flood or just with a fire? You have to deal with both at the same time because either one could kill you.”

Drescher said that these issues have become so prominent people need to start taking action.

“You can try to pull the wool over people’s eyes or people can willfully ignore this, but it’s becoming harder every day,” he said.

However, he said there is still hope for what society can do.

“On the bad news on only on the doomsday stories, 10 people are tuning out. And, and that’s not what we want either,” he said. “I hope that people will understand that our lifestyles are not sustainable, and that change is required. But the work needs to be driven by a realistic hope that we actually can do something than by the desire to want to do something because this is our planet.”

IPCC stands for Intergovernmental Panel, not International Panel ……

thanks Jim we’ll fix that