As a lawyer for Ecojustice, Julia Croome said she’s been grappling with feelings of optimism and disappointment since the federal government unveiled Canada’s 2030 emissions reduction plan on March 29.

The target? To cut emissions by 40 per cent below 2005 levels by 2030 and put Canada on track for net-zero emissions by 2050. To meet this target, the government said it will invest $9.1 billion into measures like carbon pricing, carbon capture technology, clean fuels and more sector-specific actions.

“Canada has never met a climate target it’s set,” Croome said. “That’s decades of promised targets. Copenhagen, Kyoto — they’ve all been missed.”

As an expert in governance structures, Croome is concerned about the plan’s lack of detail in breaking down these big promises into smaller next steps.

“Those are the red flags for us,” she said. “This is the kind of climate policy and climate measure that doesn’t get delivered in time and that in turn leads to another missed target.”

No deadlines, no action?

Croome said the plan’s implementation section worries her. She said several new measures are being introduced with no deadlines for completion.

“Maybe (the government has) got some of those deadlines, but they’re not being transparent about them,” Croome said. “They need to be because we have to hold them to account so that they don’t keep missing the target.”

Canada initially declared its commitment to emissions reduction in 2015 as part of the international Paris Agreement. Issued as part of the Canadian Net-Zero Emissions Accountability Act that became law in June 2021, the March 29 emissions plan is the first of four to be implemented as part of this act.

According to Caroline Brouillette, national policy manager for Climate Action Network Canada, a plan released under this act should have held the government more accountable.

“This is the first legally mandated climate plan,” Brouillette said. “However, the modeling in the plan is still disconnected from the measures the government is putting in place.”

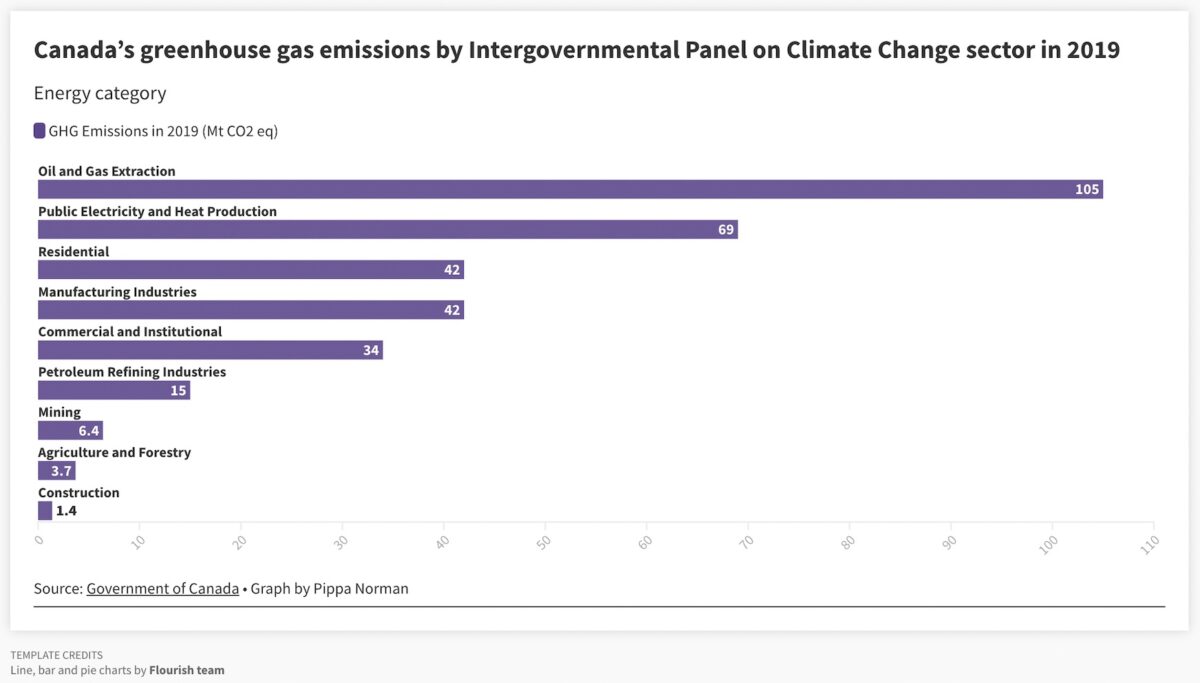

The measures outlined in the plan include electrifying more vehicles and buildings and driving down carbon pollution from the oil and gas sector. According to the Government of Canada’s “Greenhouse gas sources and sinks: executive summary 2021,” oil and gas extraction is the energy source in Canada that emits the most greenhouse gases.

Brouillette echoed Croome’s concerns over a lack of deadlines in the 271-page plan.

“We don’t have that really detailed and granular plan, where each measure is identified with the responsible minister and the timeline in which the ministers are responsible to deliver the policy’s implementation,” Brouillette said.

Public support

In a federal background report, the plan is described as “evergreen” and adaptable to different levels of ambition or opportunities for emissions reduction that arise within different sectors, such as vehicles or buildings.

Monica Gattinger, a political studies professor at the University of Ottawa, said these ambitions are promising, but not enough to hold up against “real world challenges” such as fluctuating public support for climate policies.

“If people don’t have access to reliable affordable energy, that can compromise their support for emissions reduction,” Gattinger said.

Croome agreed. She said public support is crucial if Canadians are to hold the government in power accountable to seeing this plan through.

“We need to start to see translating that narrative into actions that you’re going to take, when you’re going to take them, who’s holding responsibility, and then show us the results,” she said.

The role of clean tech

Part of the government’s emissions reduction plan includes helping industries adopt clean technology such as carbon capture, utilization and storage, or CCUS. As stated in the plan, the government plans to introduce an investment tax credit to incentivize the use of CCUS and invest $194 million to expand the industrial energy management system.

Gattinger, co-author of the report titled “CARBON CAPTURE, UTILIZATION AND STORAGE,” said CCUS will inevitably play a big role in emissions reduction in Canada.

“The emissions reduction scenarios, whether it’s for Canada or globally, show the role of carbon capture as being a very important plank,” Gattinger said. “The globe would not be able to achieve net zero without it and that holds for Canada as well.”

Canada will continue to have oil and gas in its energy systems in the future, but at much lower levels, Gattinger explained. She said already, the CCUS technology industry is developing around it with a wide array of uses for the captured carbon, such as soap and alcohol.

However, in order to bring about the implementation of such an expensive technology, Gattinger said government support needs to come first.

“It’s absolutely crucial that there be support from governments for this technology,” Gattinger said. “Whether through investing in it or through the development of tax credits.”

Looking ahead, the Canadian Net-Zero Emissions Accountability Act mandates the government deliver its first progress report in 2023. But with only eight years left in the United Nations “decade of action,” Croome said time’s running short.

“We’re two years into this key decade and these new measures really should have been further along,” she said. “We’ve got to drive down emissions faster and sooner.”