Changes to the Ontario Autism Program have parents worried about losing therapy funding, increased wait times and a lot of debt. Some were forced to sell their homes and cars to afford therapy for their children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)—even before the funding model changed.

“When we heard the announcement there was a lot of crying in our house,” said Kerry Monaghan, a mother of two children with ASD. “This is going to cut us off at the knees and it’s going to do the same for a lot of families.”

The province used to fund therapy and intensive programs for children with ASD based on a waitlist. Now families will receive a set amount based on family income and the diagnosed child’s age.

On top of the age caps, other changes include doubling funding for five diagnostic hubs in Ontario and giving funding directly to families, instead of service providers.

Lisa McLeod, Minister of Children, Community and Social Services said in a press release that the changes were made to speed up the process of eliminating the current waitlist.

There are approximately 23,000 children in Ontario waiting to receive services.

“It’s penalizing kids because of their parents’ income and because of their age and it’s not taking into consideration what they actually need to succeed,” said Monaghan.

Monaghan said the funding should be based on a spectrum of children’s needs, since Autism itself is on a spectrum.

“There’s no equity in this system. It’s a cookie cutter system,” said Monaghan.

She said she thinks this will only create backlogs in different places without enough programs and therapists in place to serve the children coming off the waitlist.

“It’s not just the money, it’s the lack of capacity with the growing number of children with autism in Canada,” said Monaghan.

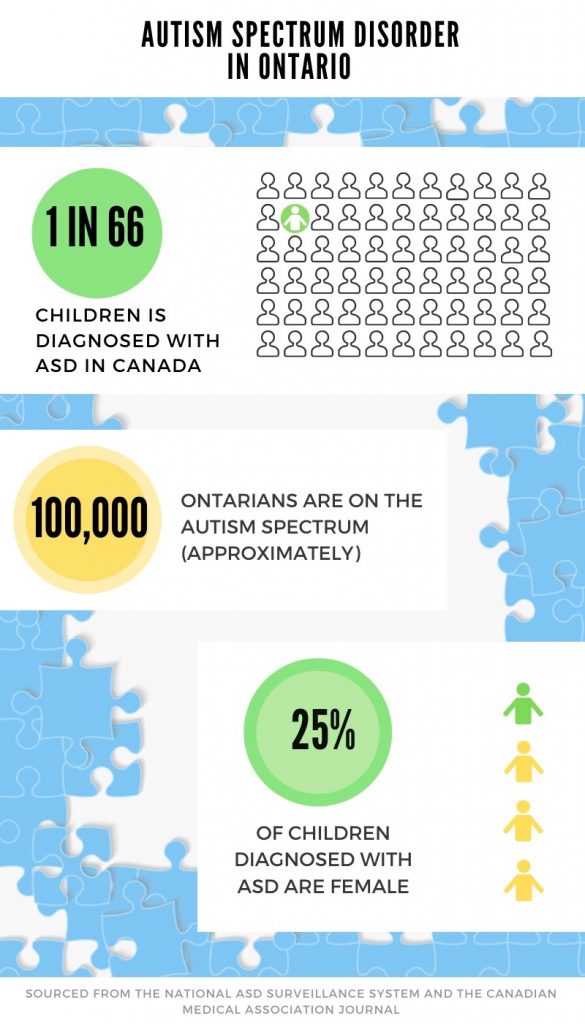

The rate of ASD is increasing in Canada according to the National Autism Spectrum Disorder Surveillance System (NASS) Report and the reason for this is still unknown.

Autism affects the typical development of the brain in the areas of social interaction and communication skills, according to the NASS.

Monaghan’s son Jack, who is five, was diagnosed with ASD through the private sector because the public waitlist to get diagnosed was too long. “We couldn’t wait,” she said.

Jack had 20 months of private therapy before he was finally eligible for provincial funding in March, 2018. The therapy was 25 hours per week and cost Monaghan and her husband $4,000 a month, totaling $80,000 before he got off the waitlist.

“To put that into perspective, there are families that were maybe a week behind me on the waitlist who are still waiting for service,” said Monaghan.

Monaghan’s daughter, three year old Charlotte, is also in private therapy and has been waiting for provincial help since July, 2017. When Monaghan checked at the time of this interview, Charlotte was number 892 on the list.

“If we ever wanted to have more kids, autism took it away from us because there’s no way we could handle it or afford it,” said Monaghan. “It’s devastating.”

Monaghan said that on the surface, the new program seems like an improvement, but the funding will run out quickly.

“It sounds like a lot of money but what people who’ve been waiting don’t realize is how much therapy actually costs,” she said.

Once Jack’s contract under the old program is over he will be granted an additional three months of therapy since he was in service before the changes. Then, he will be fall under the new system and Monaghan’s funding for him will decrease significantly.

Families with an annual household income under $250,000 will be eligible to receive funding and amounts will depend on the length of time a child will be in the program.

A child entering the program at two would be eligible to receive up to $140,000 and a child entering at age seven would receive up to $55,000, during their time in the program. These amounts are what parents would receive in total from the time a child is put into service until the day they turn 18.

If Jack were to be eligible for the maximum amount of funding, his current therapy program would exhaust the money in less than two years.

Mick Kitor, who has a son with ASD, said he has exhausted his retirement savings and “basically bankrupted” himself to fund intensive therapy that has helped his previously non-verbal son become verbal.

“This is a budget cut on the backs of the most vulnerable people in society yet again, wrapped up in fairness,” he said.

Kitor said the new funding model won’t provide any children with enough intense therapy needed to make a difference in a child with ASD’s lives.

“There’s a whole bunch of people who are wasting government money and no one’s going to get better,” said Kitor.

Kitor said the province is trying to save money, but not providing intense therapy at a young age will cost more later in the children’s’ lives once they out-age the system.

“If you intervene early enough, you can change some of those outcomes, from being a ward of the state to somebody that is going to be able to go to school, get a job and pay taxes,” said Kitor.

The doubling of funding for five diagnostic hubs and giving parents more freedom in deciding where they will seek services from, sounds good, he said.

The transfer of funds from the service providers to the parents, giving more choice in where to seek services, is positive. But, doubling the funding for diagnostic centers won’t help, according to Kitor.

“Great, more people are going to be diagnosed early,” he said. “You’re still not going to have any money and right now there’s no extra capacity for treatment,” he said.

When children start behavioural intervention between the age of two and five, they gain improvements in cognitive and language development, are better prepared for school and have better long-term outcomes in adulthood, according to the NASS Report.

Suzanne Jacobson founded Quick Start Autism, a four-month coaching program for parents of children with ASD, after her grandson was diagnosed late with ASD.

Her 14-year-old grandson was diagnosed at 2 1/2 years old.

“You can see what he missed out on and it’s non-recoverable, said MacDonald. “He’s going to need care all of his life.”

Her second grandson was diagnosed with ASD earlier and she said by 4 1/2 years old he no longer required intensive therapy. Today, the 12 year old is performing at his age-level in school.

“The difference can be as stark as a child that would need care all of their lives to a child that could live independently,” said Jacobson.

Jacobson, who speaks to many parents of children with ASD each day, said one mother told her that she and her husband sold their home to pay for the $100,000 in therapy. Another family told her they’re talking about moving to another province to see if they can get the care they need there.

“We have literally spent tens of thousands of dollars and we are not an impoverished family,” said Jacobson, “but, I had to sell a car one summer to get my hands on cash to pay for therapy.”

Children with ASD can be diagnosed as early as 18 months according to the NASS report, but the new program does not provide funding for children under two.

Shannon MacDonald, mother of three children, one daughter and one son with ASD, says one of the new program’s biggest faults is that it doesn’t consider how males and females present ASD differently.

“A lot of the time girls’ symptoms show up later,” says MacDonald. “You need to assess them differently.”

Boys have received an ASD diagnosis four times more frequently than girls, according to the NASS report.

“Now they have done the absolute worst thing they could possibly have done because they have age caps,” said MacDonald.

MacDonald said the age caps on funding will mean girls diagnosed after age 7 will never qualify for the maximum amount of funding.

MacDonald is unsure how her funding will be determined since she has two children with ASD and whether funding will carry over year-to-year if partially unused.

With only vague press releases to rely on so far, parents across the province are waiting for clarification on how exactly the changes will affect them and their children specifically.

It’s not the funding that angers parents, it’s the changes that anger parents.