The absence of the steady “drip, drip, dripping” of unleaded gasoline on her shoes is one of the first things that Kathleen Eglin noticed after making the switch to an electric vehicle. The electric cord she uses to charge her vehicle at home is much tidier and doesn’t smell as bad. But cold weather can cause more concerns. Eglin said she worries about how far she can get on a single charge, especially during this past winter and the cold start to spring.

“There is a little bit of range anxiety in the winter, as your battery life can be reduced … as the temperature drops, but this is an early-adopter problem,” said Eglin. As a director for Rightwheel, a start-up focused on reducing greenhouse gas emissions, as well as a board member for the Electric Vehicle Council of Ottawa, her daily commute stays well within city limits.

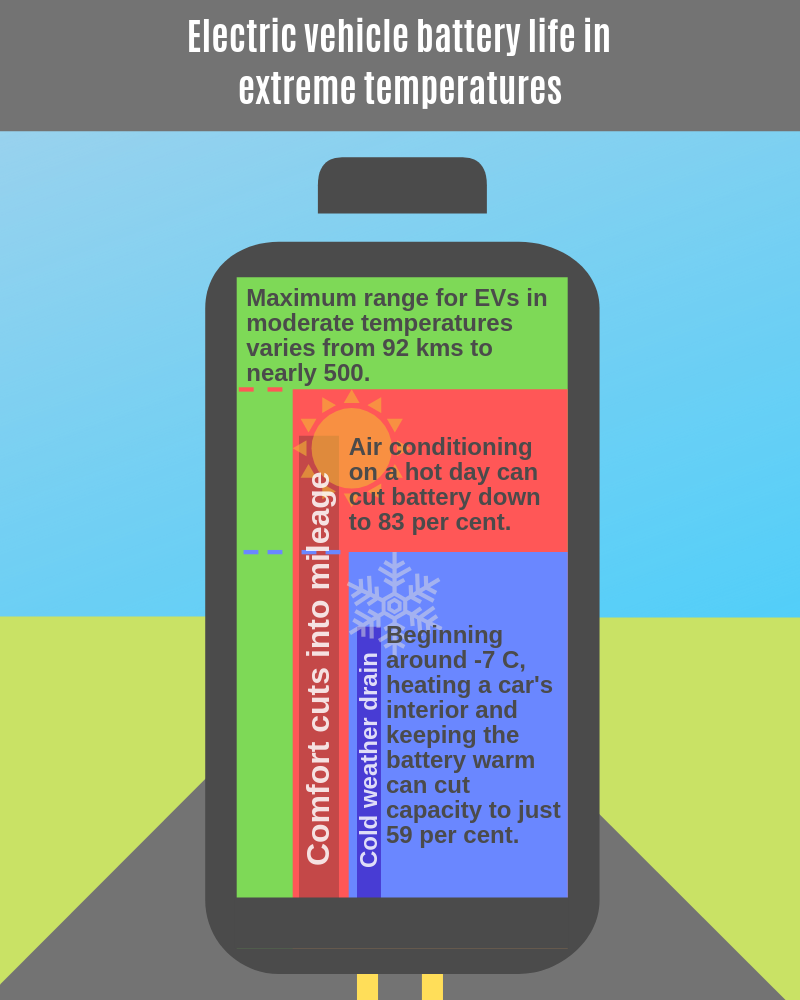

Electric vehicles, or EVs, have been criticized for underperforming in cold conditions. Reduced range, battery life, and slower charging are some of the concerns.

Lower mileage in particular can cause problems for those who drive long distances in Ontario, where EV drivers say there is a lack of accessible chargers.

“Ontario is behind,” Eglin said. “There haven’t been nearly enough chargers put in, which adds an element of worry, as you are always thinking about where you have to stop.”

A trip from Ottawa to Toronto is about 450 kilometres, meaning most EVs will require several stops to recharge. Because of a lack of chargers, drivers have to be conscious of their vehicles’ capabilities and the nearest available station.

Older EVs are especially vulnerable to an additional drain on battery life in the winter. According to FleetCarma, drivers of older models can subtract 30 per cent from the warm weather range to estimate how much they would lose in harsh winter conditions.

While the effect of external temperature varies from car to car, Eglin said vehicles with heat pump technology, which does not draw as much energy from the battery, become less effective starting at -7 degrees Celsius. Colder than that, and the energy to heat the cabin comes straight from the battery.

Since electric vehicle batteries can’t be ‘boosted’ like in a fossil fuel-burning vehicle, drivers need to budget extra time on long trips to recharge. But there are signs of improvement. While models like Eglin’s 2017 VW E-Golf can take up to 45 minutes to recharge, newer electric vehicles reduce that time, she said.

According to Eglin, as manufacturers see these problems, they work to address them in newer models. The new Tesla Model 3, for example, does not lose much of its range in colder temperatures and it can charge from zero to 100 per cent in half an hour. However, to accomplish that requires a special charging station called the Tesla Supercharger, of which there is only one in Ottawa.

More efficient batteries could ease doubts consumers have about electric vehicles, as concerns about climate change are making many people more environmentally aware.

Raymond Leury, president of the Electric Vehicle Council of Ottawa, said an urge to protect the environment might not be enough to encourage consumers.

“The older generation is unwilling to spend extra money to help the environment,” he said, referring to a study by McMaster University that found younger people are more likely to look at environmental impacts of a vehicle, while older people look at cost.

That initial cost is high. A fully electric base model Ford Focus costs just under $35,000. Provincial rebates can reduce that cost. In Quebec, the electric Ford Focus, for example, is eligible for a rebate of $8,000. The incentive program in Ontario was cancelled in July 2018. However, Leury said in the long run, electric cars are less expensive than their gas equivalents.

“The cost of operation is much lower. You’re not paying for gas, electric motors have fewer parts and don’t have the same problems as gas cars,” he said.

Charging an EV can cost just 20 per cent of what it takes to fuel the vehicle’s gas-equivalent, and Leury said the payback period for an E-Golf, unsubsidized, is three years.

According to HydroOttawa, a typical electric vehicle battery will cost less than $300 per year, or about $0.78 per day to charge at night, while a comparable gasoline car can cost between $1,000 and $2,500 annually to fuel up.

“Don’t look at the sticker price, think of your long-term savings,” said Leury.

But the promise of savings in the long run doesn’t appear to be enough. The decade-old goal set by the 2009 Electric Vehicle Technology Road Map for Canada, which aimed for half a million electric vehicles on the road by 2018, missed the mark by more than 400,000.

However, Leury is hopeful for the future. In 2018, Ontario almost doubled the number of electric vehicles on the road in the months leading up to when the government incentive program was cancelled. But he says that as the difference in cost between electric and gas vehicles narrows in the next few years, as is projected, sales will increase.

“When people see a similar price tag, hopefully it will be a no-brainer,” he said.

EV advocate Justin Larsen is a Carleton student with a passion for clean driving. He said he thinks that the “lack of initiative from government officials” with regard to the importance of climate change is a major barrier regarding the advancement of EVs.

Advancements in technology add an element of reliability to the vehicles. Eglin said hers “handles like a charm,” in snowy conditions, and the car’s regenerative braking, which reduces the chances of skidding in a car, helps recharge the vehicle by returning energy from the braking back to the central battery.

Provided it’s been charging overnight, keeping the battery warm, Eglin says her EV has no difficulty starting. “I hate winter,” Eglin said, “and not having to worry about the car not starting or standing out in the cold pumping gas is great.”