It’s 8 p.m. A message from an old friend pops up on your phone.

“Hey, hun!” it reads. You haven’t spoken to her since Grade 8, but after nearly a year of social distancing, you’ll jump at the chance to talk to anyone other than your own reflection, so you respond.

Almost instantly, she says she has a life-changing opportunity for you. And all you need is your cellphone.

“Essentially, you would run your own business,” she says. “There’s zero commitment, zero start-up fees, and you can quit any time you want.”

She then explains her involvement with multi-level marketing (MLM), a business model in which network-based companies rely on salespeople, known as independent consultants, to directly sell products and recruit people they know to join a team of other consultants.

While the idea of working your own hours by networking with others on social media sounds appealing as the pandemic sends the global economy spiralling, you ask yourself one question: is this too good to be true?

Appealing opportunity

Thousands of women are considering the question these days as they scramble to find work after losing their jobs as a result of the COVID-19 crisis. For many, the prospect of joining a team of self-proclaimed “boss babes” and selling products many already use looks more appealing than ever as a way to make quick cash from the comfort of home.

From cosmetics to diet plans, the range of products sold by MLMs is largely aimed at women – but what they’re really selling is the idea of owning your own business, being a girl boss, and making a lot of money doing it.

Even before the pandemic struck, MLMs had significant reach in Canada, despite most of the companies being based in the U.S.. By 2018, there were 1.2 million independent sales consultants in Canada and the industry made $7.3 billion in sales, according to a study by the Direct Sellers Association of Canada, the trade group representing MLMs. The overwhelming majority – 82 per cent – of the consultants were women.

Fast forward to 2020, with pandemic restrictions decimating sectors of the economy that women rely upon heavily, such as hospitality and retail, and MLMs may look like the light at the end of a never-ending tunnel.

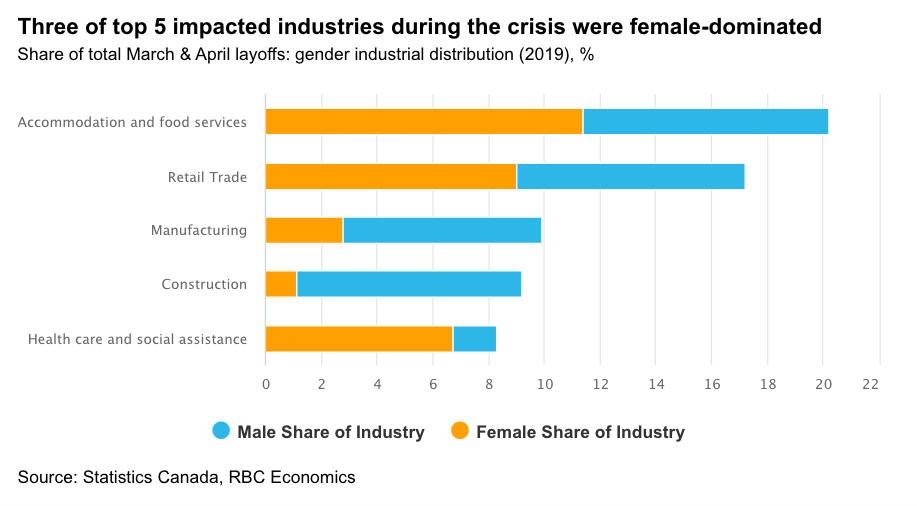

When the virus first struck, the impact on the employment of women was “unprecedented,” according to a July report by RBC Economics. The study found that 1.5 million women in Canada lost their jobs in the first two months of the crisis. Three of the five hardest-hit industries were female-dominated (retail trade, health care and social assistance, and accommodation and food services), the report found.

Throughout the pandemic, women have been more likely to have been let go from their jobs than their male counterparts. In November, Statistics Canada and RBC Economics reported that women continued to fall out of the labour force from February to October, while men were rejoining it. The data found an increase of nearly 68,000 men and a decrease of 20,600 women.

Among these women is Renée Lawson, a 19-year-old student at Wilfrid Laurier University who became an independent consultant for the vegan skincare and cosmetics brand, Arbonne, in February.

“It’s definitely helped me because at one point I didn’t have a job,” Lawson said. “I could still make money through (Arbonne). Where everything is virtual and is not necessarily dependent on having to see someone face-to-face, a business like this really helped.”

Not only has joining the company helped financially, but her mental health during the pandemic has improved as well, Lawson said.

“During quarantine, I was not doing the best because I thrive off of social connections,” Lawson said. “Just being on the team, I had a new community that was looking out for me and making sure I was OK.”

However, not everyone who has joined MLMs has had a positive experience. Erin Ball, a 23-year-old University of Saskatchewan student who also joined Arbonne in February, quit after a month when she started getting a bad feeling about the business model.

Popular sales tactic

A popular sales tactic used by MLMs is to host “parties” where consultants invite friends and family to their homes, where they can test or purchase products. With COVID-19 forcing these parties onto digital platforms, Ball participated in several virtual parties, accompanied by the friend who had recruited her. One other woman, who Ball calls the person “above” her friend in the sales chain, also joined the gathering.

Ball explained how this person “would only talk about joining Arbonne and getting your BMW and making six figures.”

The parties raised a “red flag,” Ball said.

Many MLM consultants are rewarded with cars and vacations after meeting major quotas. The more people they recruit and the more products they sell, the higher the benefits.

Ball said it all sounded like a pyramid scheme.

There’s a fine line between a pyramid scheme and an MLM: the Competition Bureau, which oversees advertising regulation in Canada, defines an MLM as a plan that focusses on the supply of products via direct sellers that potential buyers value and are willing to purchase. Companies such as Avon and Tupperware are household names that follow this business model.

Pyramid schemes focus more on generating earnings through recruiting sellers. To do so, they typically require participants to buy starter packs, and emphasize the importance of recruiting others to join their “team.” The Competition Act states such schemes are illegal and sell products that are often of little value. Supporters of MLMs say many people misjudge them because they confuse their businesses with illegal pyramid schemes.

“It’s controversial because people are confused as to what is a compliant MLM (as opposed to) an illegal pyramid scheme,” said Lewis Retik, a partner of the Ottawa-based law firm, Gowling WLG. Many of his clients are MLMs and direct-selling companies, for which he addresses regulatory compliance and commercial issues. “Without a lot of knowledge on it, they come to immediate conclusions that, you know, if it’s an MLM, it’s a pyramid scheme. It’s an unfair starting point.”

Pyramid schemes versus MLMs

While pyramid schemes can share some similarities with MLMs, they use a “closed group system” that enrols consultants who pay to participate, and who are then paid for recruiting others, he explained. Unlike MLMs, they usually don’t sell a legitimate product, but rather the idea of being your own boss. Both are known for promoting themselves as an avenue to female empowerment.

Critics say MLMs prey on vulnerable groups, selling them false promises of easy money. “Multi-level marketing uses anything that it can find to hook you into the delusional belief that (it) represents some kind of financial salvation,” said Robert FitzPatrick, author of the 2020 book, Ponzinomics: The Untold Story of Multi-Level Marketing and How Direct Selling Became an American Swindle.

The pandemic is a golden opportunity for MLMs, added FitzPatrick. “The pandemic simply offers them another tool. It’s an insidious tool.”

In 20 years of research, in which he has analyzed some 400 MLMs, he said he has never met anyone who has made a profit from direct selling.

A 2017 report by the Consumer Awareness Institute found that 99 per cent of MLM consultants in the United States break even or lose money.

“You can do better gambling,” FitzPatrick said.

And yet, more and more people are becoming consultants. Peter Maddox, president of the DSA, said recruitment has been increasing for some MLMs since the pandemic struck. While no studies exist yet to confirm this, he said he has learned through personal conversations with company leaders that “some (recruits) have had a really good time … depending on the products they sell and the way they market.”

Rising recruitment

With a business model promoting working from home, the rise in recruitment in the midst of a pandemic is understandable. Maddox attributes the increase to people being online more frequently, creating a heightened awareness of the opportunities in direct sales.

“People were seeking out the opportunities (at the start of the crisis),” Maddox said. “I don’t think anyone was out there being predatory and saying, ‘Hey, people have lost a lot of money. We’re (going to) take advantage of them by trying to recruit them.’”

However, FitzPatrick disagrees.

“It’s all predatory,” he said. “When (someone) thinks of a predator, they think of someone really evil-looking or aggressive. But that’s the characteristic of multi-level (marketing): it’s always done with a smile.”

Retik and Maddox conceded that there are some “bad apples” in the world of MLMs, but they say they believe the vast majority of direct sellers are genuinely trying to help others.

Moreover, the DSA says they’re making good money: in total, direct sellers in Canada earned a whopping $1.2 billion in annual personal revenue in 2018, the association claims. Those who don’t make money as MLM consultants were probably just looking for easy money and simply didn’t try hard enough, Retik said.

“If your goal is to learn how to sell products and you’re successful, then it was time well spent,” Retik said. If you “spent $200 on inventory and did nothing to try and sell the product … you probably weren’t the right person” to join an MLM, he argued.

This is an argument often made by MLM advocates, including Lawson.

“It’s all about what you put in,” Lawson said. “Whatever you put in, you get exactly (the same) out of it.”

While Lawson didn’t disclose the income she has made from selling Arbonne, she said she uses many of the products she buys for her inventory and doesn’t see her spending as a loss.

Hard sell

On the other hand, some MLM consultants go overboard in their zeal to sell products. This issue made headlines this spring after some consultants made fraudulent claims that their products could prevent or even cure COVID-19.

“I’ll be going live on my #IGTV in a couple of hours talking about a product which we’ve got over at #Arbonne called Immunity Support,” one seller wrote in a social media post. “Drop me a message if you’re interested in finding out more and how you can boost up your immune system right now. #CoronaVirus #ImmuneSystem.”

Promos such as that one drew the attention of the U.S. Federal Trade Commission, which issued formal warnings to 16 MLM companies, including Arbonne and doTERRA, in April. The FTC said such posts were illegal because they advertise that a product can “prevent, treat, or cure human disease” without “competent and reliable scientific evidence.”

The FTC also issued warnings to the same MLMs for claims by some consultants that they had made “substantial income” from their business venture – claims the FTC deemed to be “false, misleading, or unsubstantiated.”

False claims prohibited

Maddox said any fraudulent claims are “looked at very closely” by the DSA and the companies themselves. Moreover, the Competition Bureau prohibits false claims. An MLM could find itself in hot water if a consultant doesn’t follow its code of ethics, he noted.

“One of the issues with direct selling is the companies will put out guidance to their salespeople, but the salespeople are independent, so sometimes someone’s so enthusiastic to sell that they might stretch the truth a little bit,” he said. “It’s very important for the companies to police their (consultants) to make sure they have the tools to communicate the opportunity correctly.”

As the second wave of the pandemic continues in Canada, the promise of making big money from home as an MLM consultant will be all the more alluring for Canadian women in the coming months.

In July, the DSA commissioned Abacus Data to conduct a survey of 1,500 adults to learn about their opinions on direct selling and the financial strife caused by COVID-19; it found that 32 per cent of respondents had lost some or all of their income in the first three months of the pandemic. It also discovered that younger Canadians, students, and even those with full-time employment considered direct selling a realistic option for supplementary income. The vast majority of unemployed and part-time workers disagree for unknown reasons.

The financial toll of the pandemic will affect Canadians long after the pandemic has passed, research shows. Unsurprisingly, women will be especially hard-hit: female post-secondary graduates may lose 21 per cent of their overall earnings from the next five years because of the crisis, Statistics Canada reported in June. That is 10 per cent more than their male counterparts are expected to lose, largely because annual earnings for women are already generally lower than those for men, the study said.

Systemic inequality

It is this systemic inequality that makes women so vulnerable to unscrupulous MLM schemes, said David Vaughan, a representative from a non-profit activist group called the Anti-MLM Coalition.

“We still have a culture within the work environment that doesn’t really offer solutions for women,” Vaughn said, pointing to the failure of many workplaces to accommodate women who want or need to stay home to care for children or other family members.

“Being able to take a leave of absence from work is still jeopardizing a woman’s position in our current work culture. MLM doesn’t offer a solution – but it claims to.”