Newcomer advocates in Ottawa concerned that — as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic — children in the Syrian refugee community aren’t getting sufficient education or enough language practice to be able to adjust to life in Canada.

The pandemic has accentuated challenges facing many families in the Syrian community in their efforts to navigate the school system and other aspects of life in Ottawa.

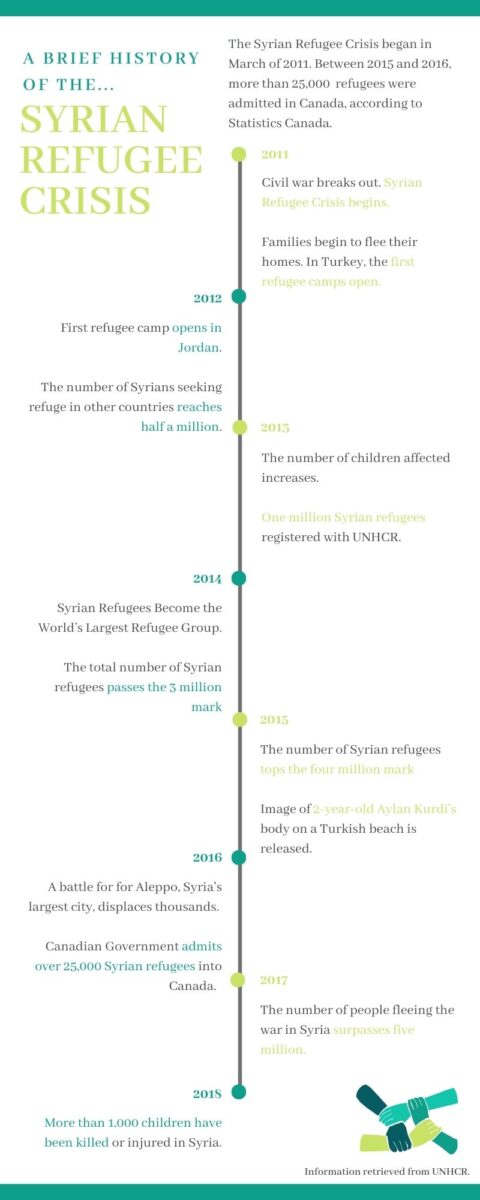

Many Canadian students are having a difficult time adjusting to virtual schooling amid the pandemic, but children in the Syrian-Canadian community face different challenges. Many no longer have access to special language training and certain online resources, all of which affects their ability to perform in school.

According to Safia Hassan, outreach lead at Sidra Treehouse, Syrian families are often very large, typically ranging from five to seven children. During the pandemic, particularly in the months of March to June, it was very difficult for them to obtain enough electronic equipment for online schooling.

“Having access to electronics for each of these children at the same time and also having a Wi-Fi that has the bandwidth to sustain their online classes has been a real challenge,” Hassan explained.

The pandemic has affected the quality of the education for children in the Syrian-Canadian community “to the point where they were slowly progressing in school and now it seems that they’re almost stagnant and not progressing,” Hassan explained.

“I do want to emphasize the fortitude, the grit, the perseverance of this community that has gone through so much and now that they’re in Canada they’re actually very grateful to be here and to be in an environment that’s safe and where they actually have opportunities for them and their children,” Hassan explained.

“But again the pandemic was really difficult and has negatively affected everybody and especially those of low income communities,” she added. “Especially the ones who are newcomers and I think it has especially affected the Syrian refugees. “

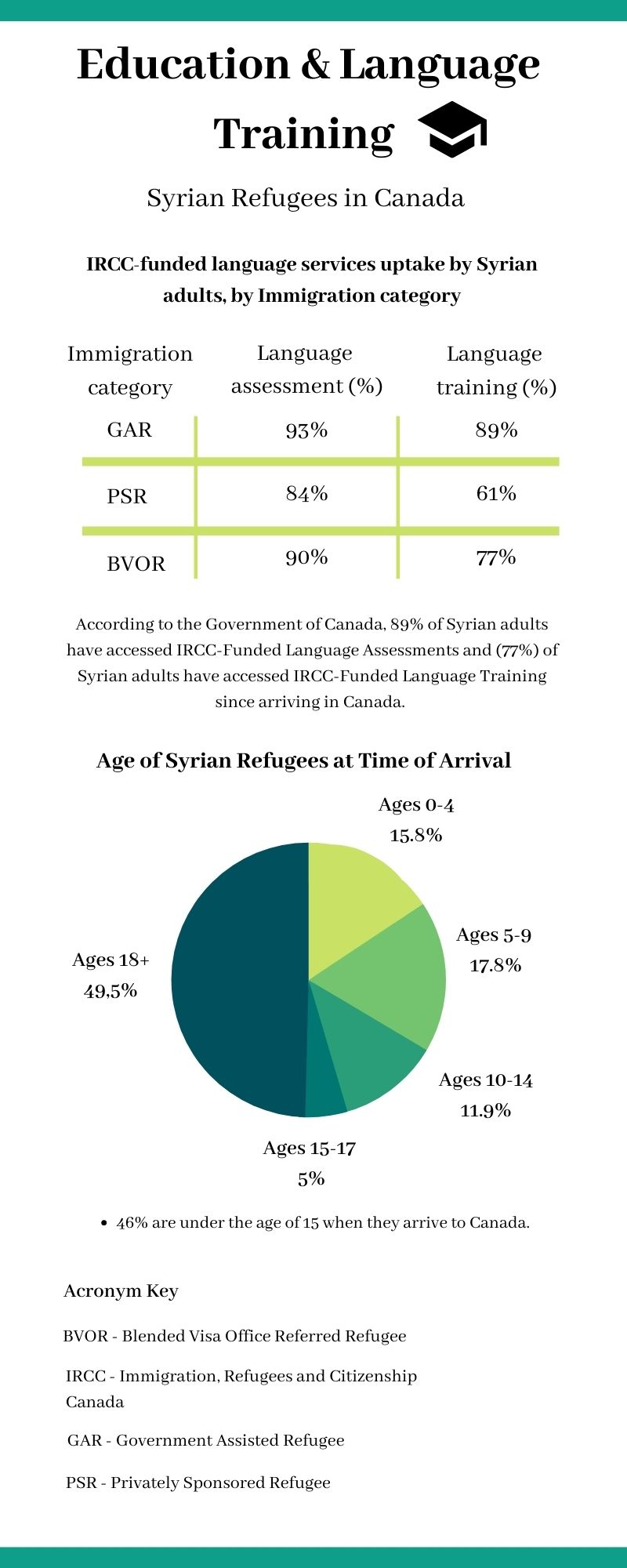

The Syrian Refugee Crisis began in March, 2011. Since then, Canada has taken in over nearly 40,000 Syrian refugees according to the federal government. In 2015, the Trudeau government announced its plan to resettle 25,000 refugees in Canada.

As a result, in 2016, there was a large number of Syrian refugees coming to Canada. There were government affiliated organizations created to off support to people who “all they’ve known is the Syrian conflict,” Hassan said. “They’ve spent the majority of their lives in refugee camps where they’ve had abysmal access to education.”

One of the organizations that stepped forward was Sidra Treehouse, founded in 2016. It is a non-profit mentorship program, located in Gloucester, that helps refugees adjust to life in Canada. Sidra Treehouse works to create a support system for new families and help children build the kinds of relationships that help with the transition.

Before the pandemic, Sidra Treehouse mentored nearly 80 children. However, once they were forced to switch to online programming because of the coronavirus crisis, they were seeing only 10 to 20 children.

But, eventually, Sidra had to stop its online mentoring in August because it was too difficult for many of the students to access the online resources.

“The online component just wasn’t working, so we had to halt those efforts, which is unfortunate,” Hassan explained.

Each of the children in the families that Sidra Treehouse works with opted for in-person schooling in the fall as a result of the challenges they faced when learning at home.

Abdulhamid Alhassun, a parent that Sidra Treehouse works with, said he and his family have been affected by the challenges of the new school system and the language barriers.

“(The) kids didn’t benefit from the online, especially (because) their language is weak, (they) weren’t able to ask and absorb the information properly,” Alhassun explained. “Concentration decreased on the online especially because they’re not good with technology.”

According to Alhassun, his children were hesitant to participate during online classes running from March to June because of language challenges.

For Alhassun and his wife, seeing their children upset and not being able to support them made them feel helpless.

Alhassun has five children. Two are at the elementary level, one in middle school and two in high school. They are all attending school in person now.

On separate occasions, Alhassun and his family have had to quarantine because they were unable to access the online resources to register for testing, resulting in each child missing multiple weeks of school and putting them further behind in their classes.

In one case, one of Alhassun’s sons had a cold and was sent home from school. He tried to get tested but couldn’t figure out how to register online. So instead, he quarantined for 14 days and missed school.

There was another incident in which a student on the school bus was exposed to COVID-19 and everyone on the route was asked to get tested or quarantine. Once again, Alhassun and his family had to isolate for 14 days and his children missed more school.

Alhassun and his wife were in language training themselves when the program moved online in March. It didn’t severely affect Alhassun, but he experienced difficulties trying to learn through his phone because he didn’t have access to a laptop.

According to Alhassun, his wife was more affected by the transition than he was. She’s in Level 1 language training and he’s in Level 4. His wife is still taking language training, but Alhassun has stopped.

“Integration has been affected,” explained Hassan, “and as it relates to the education of our children, it has definitely been affected.”