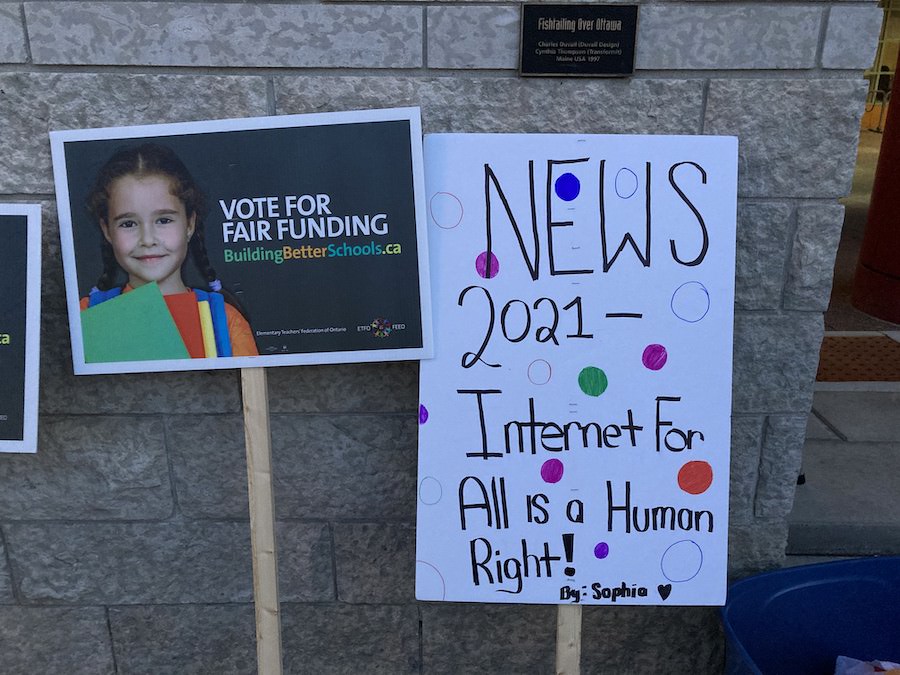

Drums and cheering could be heard outside Ottawa City Hall on Nov. 16 as ACORN members and other activists advocated for the recognition of internet access as a human right.

As the world moves into a digital sphere, internet rights advocates say many people are being left behind in the transition.

ACORN Ottawa led the rally at Marion Dewar Plaza, along with members of the Ottawa Carleton Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario and Ottawa Catholic Teachers.

“We are turning to the City of Ottawa to establish a municipal broadband service the same way it is being done in other major cities like Toronto,” said ACORN member Ray Noyes in a statement issued ahead of the rally. “And as our allies in this issue, no-one knows better than teachers how important good affordable internet access is for education.”

The rally was part of ACORN’s #Internet4All campaign and spotlighted what protesters consider a matter of justice and equality of access for all families in Ottawa, according to an OCT tweet.

“We are turning to the City of Ottawa to establish a municipal broadband service the same way it is being done in other major cities like Toronto. And as our allies in this issue, no-one knows better than teachers how important good affordable internet access is for education.”

— Ray Noyes, ACORN member

ACORN Canada, the social and economic justice advocacy group, has previously organized protests demanding that access to the internet be free during the pandemic for all low-income Canadians. The group held rallies across the country in June to draw attention to the issue.

The Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now is a national organization representing low- and moderate-income families with more than 130,000 members in 24 chapters in nine Canadian cities, including Ottawa.

ACORN and its allies are pressing the City of Ottawa to “create a publicly owned, municipal broadband program” to provide low-cost internet service, to “expand free Wifi in all public spaces (i.e. bush shelters, parks, etc)” and “expand programs that offer free and subsidized devices.”

ACORN’s fight to bring accessible and affordable internet to economically marginalized Canadians started in 2013 with the group’s advocacy for Connected for Success and Connecting Families programs. In 2014, ACORN Nova Scotia member Jordan Thomas presented a letter to internet service provider and telecommunications giant Eastlink, demanding a meeting to discuss the urgent problem that many low-income families have in common: not being able to afford high-speed internet.

“Digital inequity doesn’t just exist in Ottawa, it exists all across Canada” said Andrew Martey Asare, who works at National Capital Freenet, a leading partner with Digital Equity Ottawa.

The Neighbourhood Equity Index, a tool to assess and compare unfair differences at a neighbourhood level on factors that affect wellbeing, has been investigating digital equity in Ottawa.

According to the Index, digital equity is the ability of individuals and groups to access and use information and communication technologies.

The Neighbourhood Equity Index is a project led by the Social Planning Council of Ottawa, in partnership with United Way Ottawa and the City of Ottawa. Other partners supporting the initiative include the Ottawa Community Foundation, Ottawa Neighbourhood Study, Ottawa Carleton District School Board, Ottawa Public Health and the Ottawa Police Service.

Digital Equity Ottawa states that digital inclusion takes in access and includes a wide range of issues: available hardware, connectivity, digital literacy and the capacity of the non-profit sector.

While the fight to close the digital divide is ongoing, the issue is not a new phenomenon.

In 2016, the Canadian Radio-Television and Telecommunications Commission declared broadband internet a basic service.

In 2018, the federal government launched its Connecting Families program, which gives National Child Benefit recipients $10 a month to help get internet service.

But, Freenet’s Asare said, it’s hard to pull all the information together to qualify for the program. “I can’t imagine how hard it would be for others to find resources.”

Asare said low-income and some moderate-income households that can afford internet are also probably making some sort of trade-off.

“Low-income seniors, single-occupant households and many more will not qualify. The Connecting Families program is voluntary and not all telecommunications companies have opted to take part,” a 2019 ACORN report, Barriers to Digital Equity in Canada, concluded.

Asare says digital access is a federal, provincial, and municipal issue, but, he added, because there is such a strong business interest “in the end, it will always be the consumer that will suffer.”

In the 2019 budget, the federal government committed to a multi-year plan that will provide high-speed internet access for all Canadians by 2030. But the commitment did not outline a plan to tackle internet affordability.

“Most people think the divide is closing, and it kind of is,” said Asare. “We have more people online now than ever, but we aren’t thinking about affordability, what type of access and what quality of access.”

Households with incomes of $30,000 or lower were less likely to have home internet access than those with incomes more than $60,000. Only 76 per cent of respondents with household incomes below $10,000 have home internet, said the ACORN report.

“Paying for internet is so essential, but then you’re giving up money on food, transportation and more.”

The report identified cost as the major barrier to digital equity, and respondents reported that internet services are too expensive, said the report.

That is a concern because online access is increasingly important to apply for jobs, complete schoolwork, download government forms, pay bills and connect with families and friends, said the report.

It argued that internet access has become a basic human right.

“The way that the government looks at accessibility is through a service availability mindset,” said Asare. “If the physical lines are available, then they check a box. But it doesn’t account for who isn’t connected, and how well they are connected. If we consider it a right, then the government should look at access more holistically.”

A year ago, the House of Commons Industry Committee began work on a comprehensive study on accessibility and affordability of telecommunications services in Canada.

The report was tabled this past June. It concluded that access to the internet is essential.

There are mainly little movements in Ottawa, said Asare. “None of the people working on it have the authority to move it forward on the rights level. … We need more powerful institutions to address this as a serious issue.”

Nasma Ahmed, a technologist, and Toby Harper-Merrett, an information and communication technology developer, recently argued in a report for the Toronto-based think-tank First Policy Response that everyone should be able to use the internet, but the chasm between those who do and do not have access will not be closed, filled, or bridged by technology alone.

The Digital Equity Ottawa report and its recommendations were generated in response to the impacts of COVID-19 lockdowns. During the pandemic, the internet became the main way people accessed all parts of society: work, school, government, social services, friends, family, entertainment, food shopping, health care and more, the report noted.

“The cost of digital exclusion,” the report stated, “is the cost of choosing to leave people behind in nearly every aspect of society — including economic success, educational achievement, positive health outcomes and civic engagement.”

Amhed and Harper-Merrett argued that issues of digital equity are deeply rooted, connected, and systemic. Women, Black, Indigenous, and people of colour, people living in rural and remote communities, those who are low-income, and those living with disabilities are at higher risk of digital exclusion.