Many Ontario residents living with disabilities say they are concerned about the easing of provincial and local COVID-19 restrictions. They say the changes will expose many of them to greater risk of infection, serious illness and potentially death.

Since the start of the pandemic, people with disabilities have been concerned about the lack of awareness of the impact of COVID-19 on those with compromised immune systems, serious respiratory conditions and a range of health challenges.

Those concerns were heightened after the Ontario government began easeing COVID-19 restrictions on Jan. 31. Indoor settings were reopened with a 50-per-cent capacity limit. Starting today, proof of vaccination is no longer required for most activities in Ontario. Masking continues to be mandatory indoors, but Ontario Premier Doug Ford indicated Monday that could change soon.

People with disabilities fear the eased restrictions — at a time when the COVID-19 pandemic is not yet over — will make them even more vulnerable to infection.

According to a Canadian-led study published last year by the Disability and Health Journal, the virus affects disabled people more severely, as it can complicate and worsen pre-existing health conditions.

Ottawa resident nat weeks uses a wheeled walker to get around Ottawa’s snowy streets. They said they are upset about Ontario’s handling of the pandemic.

Weeks has contracted COVID-19 twice, in February 2020 and in December 2021. Since then, their health has gotten worse. They have developed chronic nosebleeds and a cough that’s triggered by eating.

“I know that with the pandemic continuing, and the rate of worsening health each time I get it, I will die of COVID one day,” said weeks. “My biggest fear is that I will have not gotten enough time to make some kind of legacy beyond me.”

Em D’Orazio, an Ottawa resident with a respiratory issue, is also not happy about the easing of restrictions.

“They’re just getting it wrong because they don’t have the grasp on what disabled people or people with disabilities are already struggling with,” said D’Orazio. “It’s difficult seeing able-bodied people and politicians not getting our experience and not being able to empathize. It’s not a picnic for all of us.”

Because of their respiratory issue, D’Orazio’s immune system is weaker than most people’s.

Even though D’Orazio has not contracted COVID-19, they have discussed the potential impact of the virus with their doctor. D’Orazio said they would suffer more than the average person.

Symptoms could include heightened discomfort, prolonged recovery and the potential for various “long COVID” health problems.

Heather Walkus, acting chairperson of the Council of Canadians with Disabilities, said she’s also angered by the lack of concern about the potential impacts of eased pandemic restrictions for the disabled community.

“One of the failures of the government and society has been to include people with disabilities as an equal group,” she said. “They promised they would support us and include us in emergency planning, and in this case, they did not.”

Walkus said this is a trend that has persisted since the start of the pandemic.

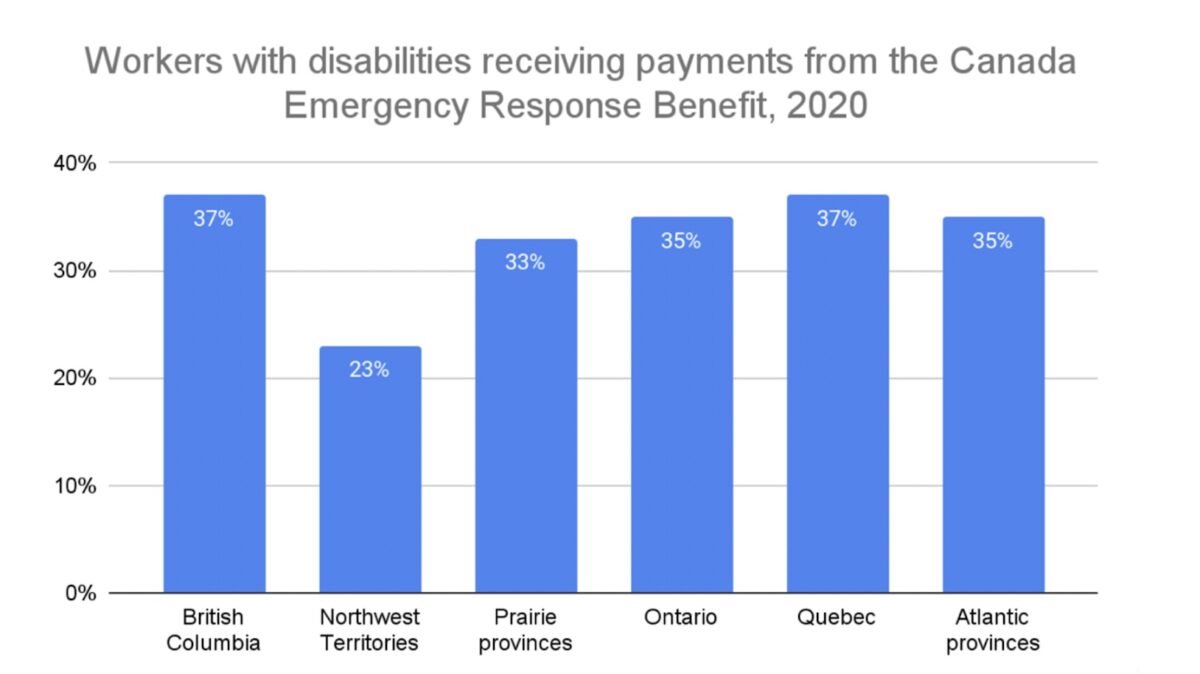

In 2020, for example, advocates for people living with disabilities criticized the rules for receiving payments under CERB — the Canada Emergency Response Benefit. CERB was offered to employed Canadians who had lost all or some of their income because of COVID-19.

Because workplaces often discriminate against people with disabilities, many struggle to find work, said critics of CERB from the disability community. As a result, those who were unemployed could not benefit from CERB and faced greater financial hardships during the pandemic.

According to Statistics Canada, only about 35 per cent of Ontario workers with disabilities received CERB payments.

“Governments don’t make good decisions without us at the table,” said Walkus. “You must consider the impact of your decisions on a range of people, and you may have different ways of ensuring equity. That is key.”

“Governments don’t make good decisions without us at the table. You must consider the impact of your decisions on a range of people, and you may have different ways of ensuring equity. That is key.”

— Heather Walkus, acting chairperson, Council of Canadians with Disabilities

Eliza Chandler, professor of disability studies at Ryerson University, points to ableism as a key problem with the easing of COVID-19 restrictions in Ontario.

“It’s the fact that when these policies are enacted, they imagine a non-disabled person,” said Chandler. “It’s no surprise that this latest round of lifting restrictions simply doesn’t think about putting disabled people at increased risk.”

Chandler said governments need to see members of the disabled community as valued citizens.

“It doesn’t matter what they say about encouraging inclusivity. Unless there’s change, we’re only going to see more and more disregard of disabled peoples’ lives.”