The Salvation Army’s controversial plan to build a 350-bed men’s only shelter in Vanier remain in limbo after concerned residents challenged the project before a provincial tribunal last month. The community groups hope their challenge will stop the project. A decision by the tribunal isn’t expected for months.

This comes as the city has declared a housing emergency in Ottawa because of rising house prices and rents and low vacancy rates along with a lack of affordable housing.

Here’s what you need to know about the Vanier project.

How did we get here?

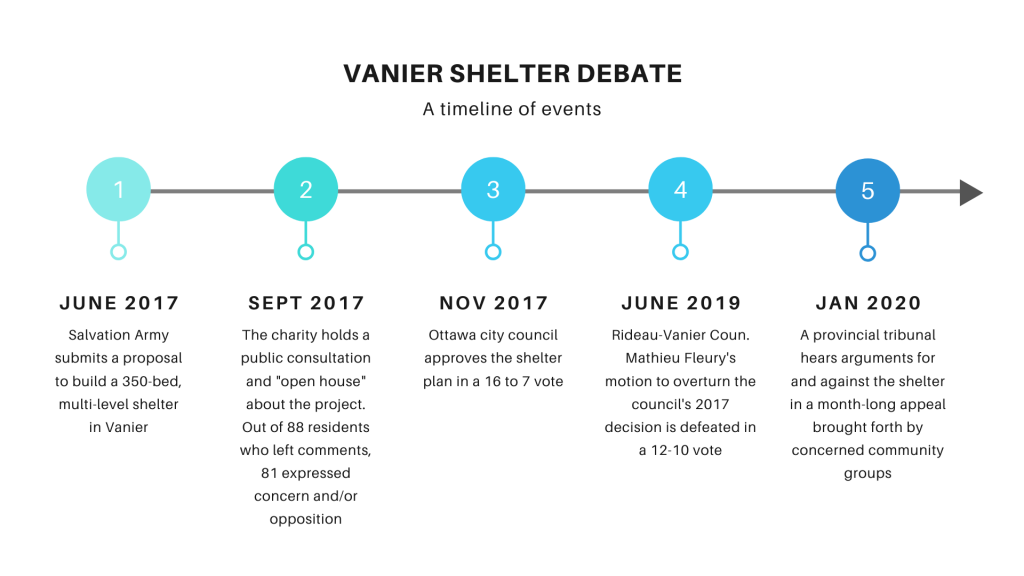

In November 2017, council approved the construction of a new Salvation Army shelter and service centre on a property at 333 Montreal Rd. The charity’s proposed “community hub,” which will replace its aging facility on George Street in the Byward Market, sailed through with a 16-7 vote.

The move was met with strong opposition from the Vanier community, which voiced its disapproval with protests, petitions and the creation of SOS Vanier, a group dedicated to fighting the project. According to a committee report released in October 2017, nearly 90 per cent of people who provided feedback to the city were opposed to the shelter or had concerns.

Lynn Zeitouni, a Vanier resident for 50 years, says the Salvation Army failed to take the community’s input into serious consideration before they pushed ahead with the proposal.

“They did not do any consultations,” says Zeitouni. “They did presentations and those are very different.”

In June 2019, Rideau-Vanier Coun. Mathieu Fleury urged council to reconsider its decision in light of information revealing the Salvation Army didn’t yet own the property on which it was to break ground. The motion was defeated 12-10 vote with two councillors absent.

Meanwhile, the community appealed to the Local Planning Appeal Tribunal, which hears cases on land use matters.

How does the appeal work?

The hearing, which began on Jan. 13, ran for more than two weeks. An adjudicator heard from lawyers on both sides on the fate of the shelter proposal.

In an emailed statement, Glenn van Gulik, the Salvation Army’s spokesperson, wrote that the “community hub will serve a broad range of community needs while acting as a catalyst to the redevelopment of Montreal Road.”

The opponents say the facility is too large and that it’s in the wrong place.

Urban economist Dan Stankovic, who was the city’s director of housing and economic development for 10 years, says a 350-bed shelter would make it the second largest in Canada.

In addition, Stankovic says the project “is simply an outdated and ineffective approach to addressing homelessness.”

Rather, he says the city needs to focus its efforts on the “Housing First” initiative, a program which works by quickly moving people experiencing homelessness into independent housing and providing followup support.

“Housing First has been shown to work more effectively,” says Stankovic.

Drew Dobson, leader of SOS Vanier and the owner of Finnigan’s Pub — a business just east of the shelter’s proposed site — agrees.

“Hiding the homeless is not the same as helping the homeless. What we hope the city would do is change their policy and actually work on creating homes,” says Dobson.

What will the shelter look like?

The Salvation Army initially proposed a multi-floor facility with 350 beds, including 140 for emergency use, 110 for people with addiction and health issues, 58 for participants in the work and life skills programs and 42 for men with developmental challenges.

The plans also include a new thrift store, coffee shop and free event spaces available for community use.

Why is the location so controversial?

The shelter’s proposed location at 333 Montreal Rd. is a major issue in the appeal. The site, currently occupied by a motel, is on a traditional main street of the community surrounded by businesses and residences.

Living in a community that many feel is too crowded with shelters and social services, Zeitouni says she already finds it difficult to walk around at night.

“I don’t always want to go outside my door and be confronted with somebody who has a major mental health issue or who is begging,” she says.

As a business owner just steps away from the proposed site, Dobson says the location is “not zoned properly for a shelter.”

City policy states that shelters should not be built on main streets or in residential areas but zoning laws were amended to allow this project. The 2017 committee report cites the new shelter’s proximity to health and resource centres as a reason why it’s a “compatible” fit in the area.

However, opponents argue the concentration of such services is another reason why the project should be reconsidered.

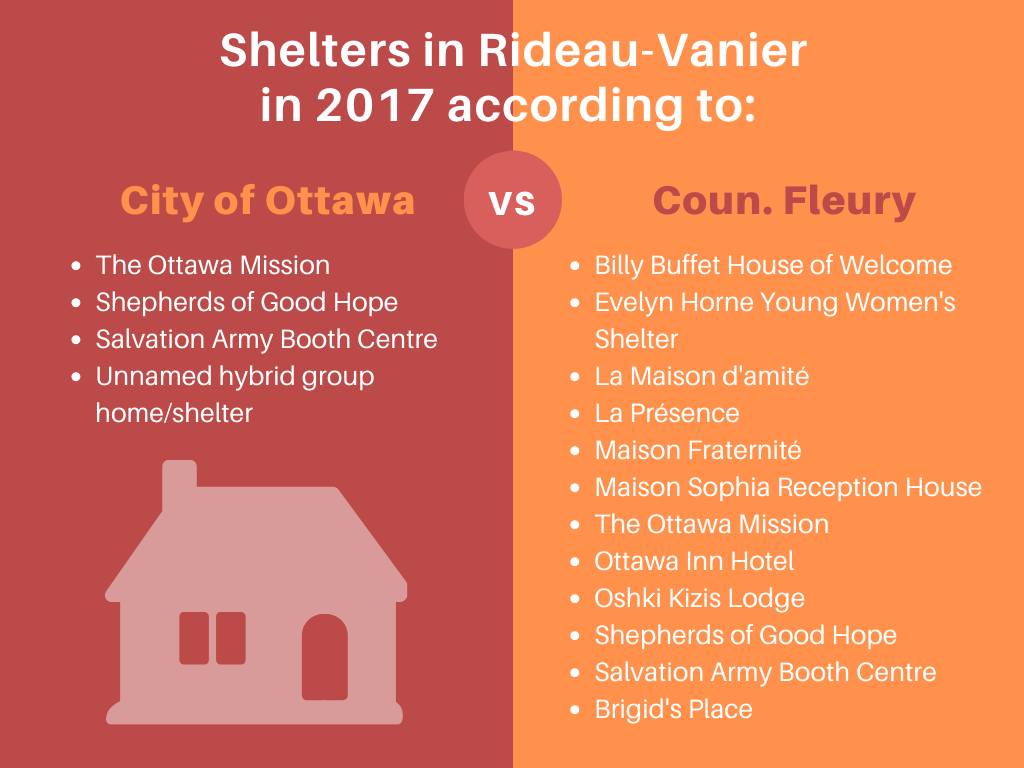

In 2008, the city capped the number of shelters in the Rideau-Vanier ward at four, but Coun. Fleury argues there are, in fact, 12 facilities functioning as “shelters” according to the city’s definition.

For Dobson, the shelter poses a “major roadblock” in Vanier’s economic and social development that will set his community back 10 years.

“Now I feel like it’s our obligation to try and stop this proposal in order for Vanier to have a bright future,” he says.