Physical distancing restrictions and strict hospital policies have made giving birth since the beginning of the pandemic an isolating experience for some mothers.

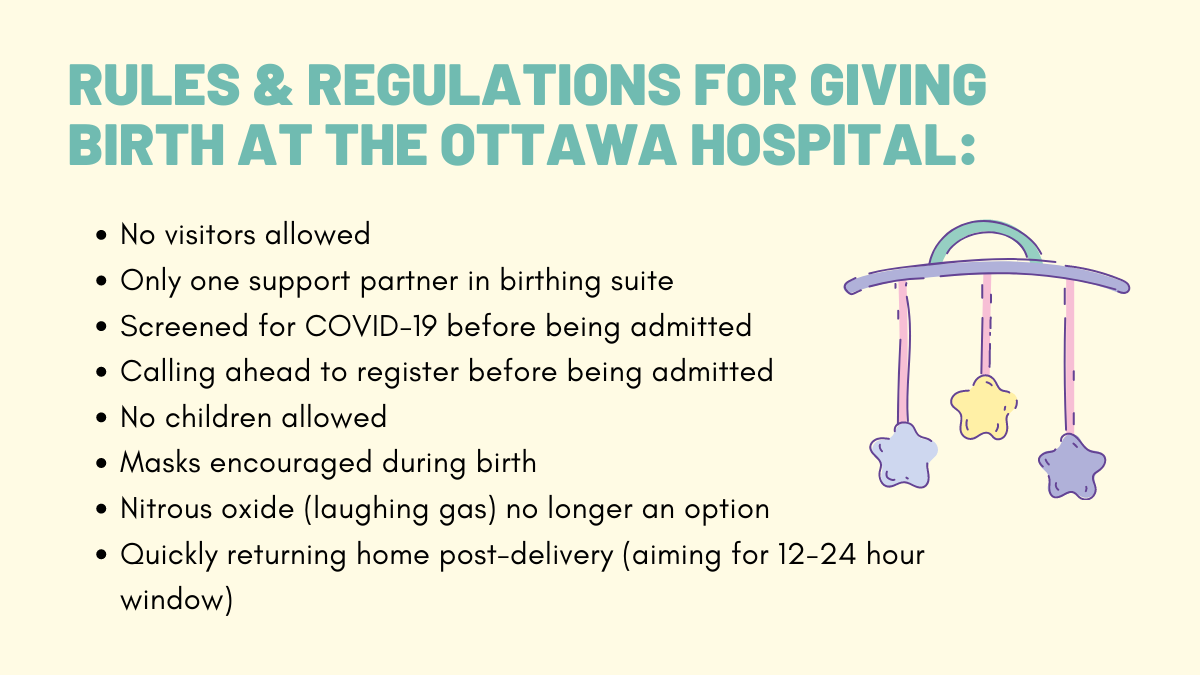

Since the onset of COVID-19 in early March, Ottawa hospitals have enforced strict regulations across their campuses and birthing units, including a “no visitors” policy.

At The Ottawa Hospital, support partners who have been assessed for COVID-19 symptoms can join expectant mothers in the birthing suite, but only after mothers are admitted to the hospital.

The new restrictions surrounding giving birth can leave mothers feeling confused and stressed.

Terianne Muhl, 39, who had her fourth child in May, said her experience was anything but smooth.

“It was awful. It was really difficult. Even for weeks after, when I thought about it, I would just start crying because it was so lonely,” she said.

Muhl said she gave birth in the hospital without a partner. Her husband stayed home and watched their other three children. The couple was also worried about mixing households by having friends or a family member babysit if he went to the hospital with her.

To minimize the COVID threat, hospital policy meant that once joining a mother in the birthing suite, the support partner isn’t allowed to leave and come back.

While the birth was lonely, Muhl said COVID-19 restrictions have also meant that cousins, grandparents and other family members haven’t had the chance to hold or meet the new baby in-person since she’s been home.

“The baby is almost seven months old now, and none of his family, except us, has met him. I feel like it’s such a robbed experience,” she said.

This sentiment is echoed by Salma Abdi, 35, who gave birth to her daughter in September at The Ottawa Hospital. Abdi said not being able to celebrate with family and friends feels like she hasn’t even given birth at all.

“It’s like a pregnancy that never happened. I didn’t see anyone when I was pregnant. Some people don’t even know I had a baby,” she said.

Abdi said she has stayed connected to family and friends by calling and sending pictures of the baby.

“The joke is, ‘we’ll probably see the baby when she’s walking,’ and at this rate that’s what it looks like,” Abdi said.

The restrictions of the pandemic, such as wearing a mask, were also an added stress while giving birth, Abdi said.

“All I remember is the nurse putting the mask on my face while I’m trying to give birth. I’m like, ‘I’m having a hard time breathing, I can’t do this,’ ” she said.

Despite hospital policies banning visitors and allowing only one support partner, some other birthing facilities follow different rules.

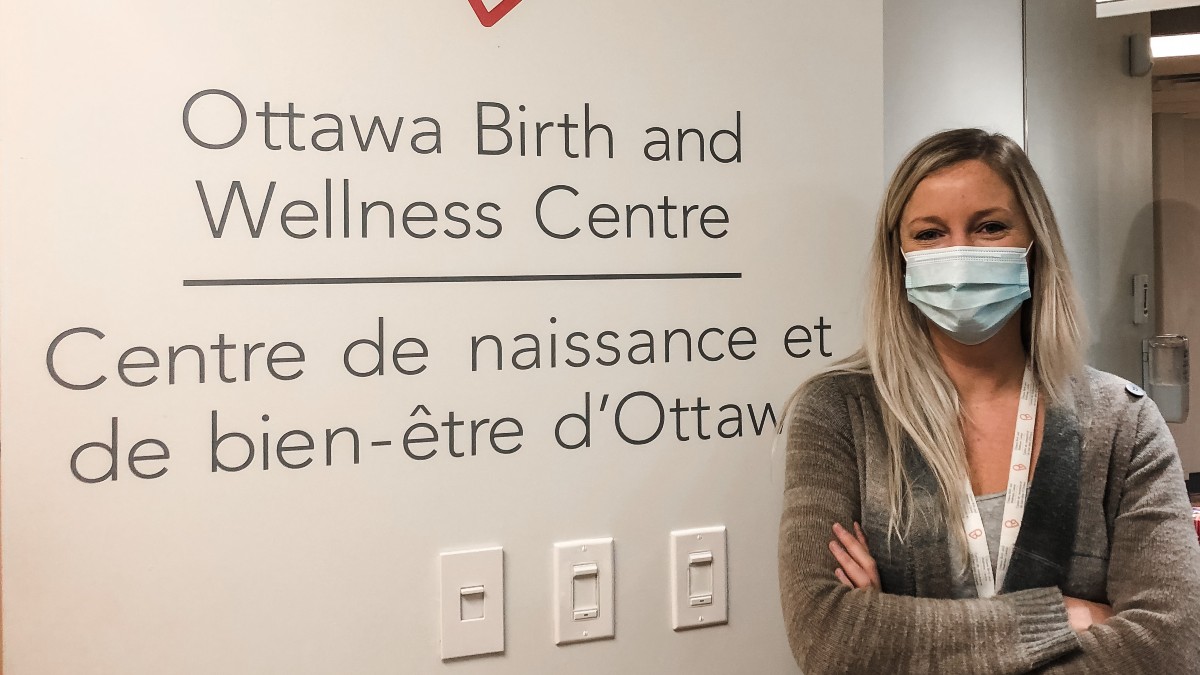

Mothers at the Ottawa Birth and Wellness Centre (OBWC) can have up to six people in their birthing suites, which includes the birth mother, two midwives and three support persons of the mother’s choice.

Tamara Brown, executive director of the OBWC, said the centre’s smaller facility — with only three birthing suites — makes it much easier to keep everything sanitized than in a larger hospital.

“Birthing people are experiencing a whole new level of stress and anxiety in their pregnancy and in the period of being a new mum or new family,” Brown said, adding the centre does its best to provide a calm and safe environment.

The OBWC also provides wellness support and community programming, which has now moved online during the pandemic.

In partnership with the Royal Ottawa Mental Health Centre, the centre holds regular events through Facebook Live, including sessions on anxiety, dealing with birthing trauma and weekly online groups facilitated by a social worker.

Brown said it’s even more pertinent now to provide online support for new mothers who might be feeling overwhelmed or increased loneliness throughout COVID-19.

“It’s really a great way to facilitate connections between mothers virtually when there’s not a lot of opportunities to do that in-person,” she added.