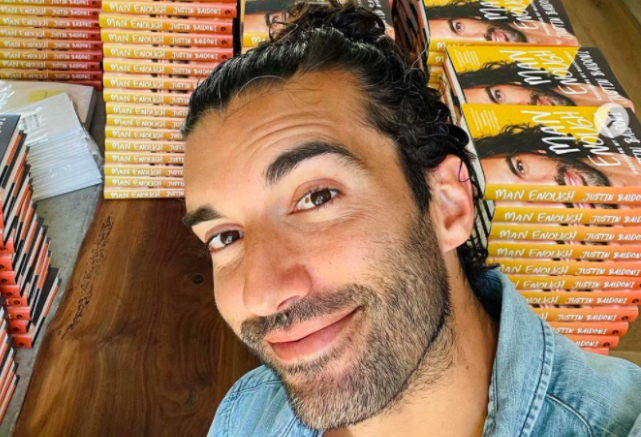

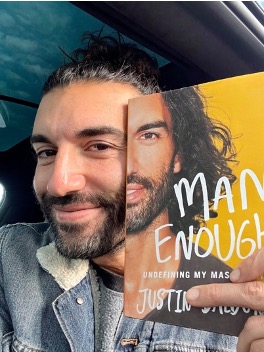

Justin Baldoni, the American actor and director best known for his role as Rafael Solano in the TV series Jane the Virgin, is releasing his first book — Man Enough: Undefining My Masculinity — on April 27.

This 10-chapter, semi-autobiographical book shares Baldoni’s personal experiences battling with gender roles, ideals of masculinity, harmful ideas of manhood and vulnerability in an effort to understand, as well as redefine, what it means to be a man.

The conversations Baldoni has shared thus far in his TED Talk from 2017 and a limited series have inspired many around the world — especially those who have advocated for years to promote pro-feminist messaging from men and to discourage harmful forms of masculinity.

Baldoni says in the introduction that he hopes the chapters are invitational — sharing his own experiences and thoughts on masculine culture so that others can do the same.

“Other boys first taught me —scratch that — enforced the rules of masculinity, and handed me my first script that told me what was okay, what was not okay, and set the rules for how I must act to become a man. These rules stacked on top of each other over time, creating a suit of armour that I would wear for decades,” writes Baldoni.

“I’m 100 per cent not ashamed to say I love being a man. I am also not apologizing for being a man. But that is not to say that I won’t be apologizing for the ways in which my interpretation of masculinity has hurt those around me.”

Baldoni says he wants to explore behaviours and feelings men experience such as anger, unhappiness and pressure. He says these feelings are sometimes bottled up because of the fact that society instills the importance of “alpha male traits” such as being strong, sexy, brave, powerful, smart and successful.

Baldoni notes that toxic ideals of masculinity sometimes lead into bigger issues. While they can cause challenges for men in their own lives, such as depression and substance abuse, they can also lead to broader issues that men cause at much higher rates than women — from various acts of violence, to sexual assault, rape, exploitation and more.

Lisa Hickey, media representative at The Good Men Project – a U.S. publication devoted to the changing roles of men in the 21st century — is one of a number of observers who says Baldoni’s use of his public profile to advance the cause might help spread awareness of these issues.

“Justin has a way of talking to men in a way that they can understand,” said Hickey. “We really need more men stepping up and saying, ‘OK, I see the problem and I’m going to talk about it and I’m going to talk about it in a way that relates to other men.’”

Nadia Abu-Zahra, associate professor and joint chair in women’s studies at Carleton University and the University of Ottawa, notes how Baldoni can effectively reach people because of his celebrity platform – since many people already feel like they know and trust him.

Hickey agrees that this is an important factor. She said she has witnessed how hard it can be to reach men and bring them to the table to talk about topics which are uncomfortable, or even taboo.

In the past two years, she said resistance to these conversations has started to grow, manifesting itself in anti-feminist movements and the emergence of “men’s rights” extremist groups such as Incels, A Voice For Men and Return of Kings—the social context for normalizing a variety of acts of violence against women.

Harassment and violence against women has been highlighted in recent weeks after 33-year-old marketing executive Sarah Everard disappeared in South London on her way home from a friend’s place. Her body was found a week later.

This event mobilized vigils and protests around the country and across the world, mourning the loss of “Sarah” and many other women.

On March 10, UN Women UK released statistics on sexual harassment in public spaces, notably highlighting the fact that only three per cent of women aged 18-24 reported that they had not experienced any sexual harassment in their lives.

Following this report, the hashtags #97percent and #allwomen were trending on TikTok, garnering more than 300 million views. These videos were addressing the seemingly hurtful responses from some men, with #notallmen trending on Twitter as a response to protests following Sarah’s death.

The absence of empathy among some men following this tragic event derives from an unwillingness to acknowledge the need for change, said Jeff Perera, Toronto educator and activist.

He says men can get into a “fight, flight or freeze mode” when social issues such as sexual assault, violence and the harassment of women are highlighted as an effect of toxic masculinity. He says some men mislabel accountability as cancel culture — in which some people are forced or shamed out of social or professional circles.

“Men like me will say, ‘Hey look, it’s not all men, it’s a handful of guys. Most men are good men’,” said Perera. “In reality, most men have been disappointing or harmful. When we talk about gender issues or sexual assault or harassment, we automatically think of Harvey Weinstein, Jian Ghomeshi or Bill Cosby, but it’s not just that extreme. It’s the everyday stuff we do as guys that contributes to this culture.”

Michael Kehler, masculinities research professor at the University of Calgary, notes how defensiveness emerges out of a place of privilege, and explicitly impedes progress.

“Many men are too busy defending (saying), ‘That’s not me’,” said Kehler. “It would be much more productive and healthier to actually accept that in many cases we are complacent in certain cultures— locker room cultures for example— where we don’t routinely speak up against misogyny or sexism and violence.”

Kehler notes that a perfect example of men recognizing a problem rooted in toxic masculinity were the events taking place in some Montreal high schools last year.

In October 2020, protests in co-ed private schools across Quebec ensued, with boys taking it upon themselves to wear skirts to school to protest sexism and gender-based discrimination against women and girls.

Colin Renaud, a student at Villa Maria, a private high school in Montreal, was one of the first boys to wear a skirt to school. He said he wanted to fight against the hyper sexualization of women’s bodies.

His message, spread on social media, encouraged boys from Collège Nouvelles Frontières, College Laval, Lucille-Teasdale International School and College Charles-Lemoyne to join in on the protest.

Kehler noted how these events, a perfect example of allyship, shows how gendered stereotypes of the role of men and boys can be subject to intentional change.

Perera has worked with young men since 2008 on facilitating this kind of change, and notes that men today have more of an opportunity than any other generation before them to be mindful of how masculinity has harmful blind spots.

“For me, growing up – I’m 45 – there were no conversations like what is happening now. Back then it was really hard to find some of the discourse that you’re seeing now,” said Perera.

“That’s why Justin’s book is so important. He’s providing you (with) examples of how things could look different.”