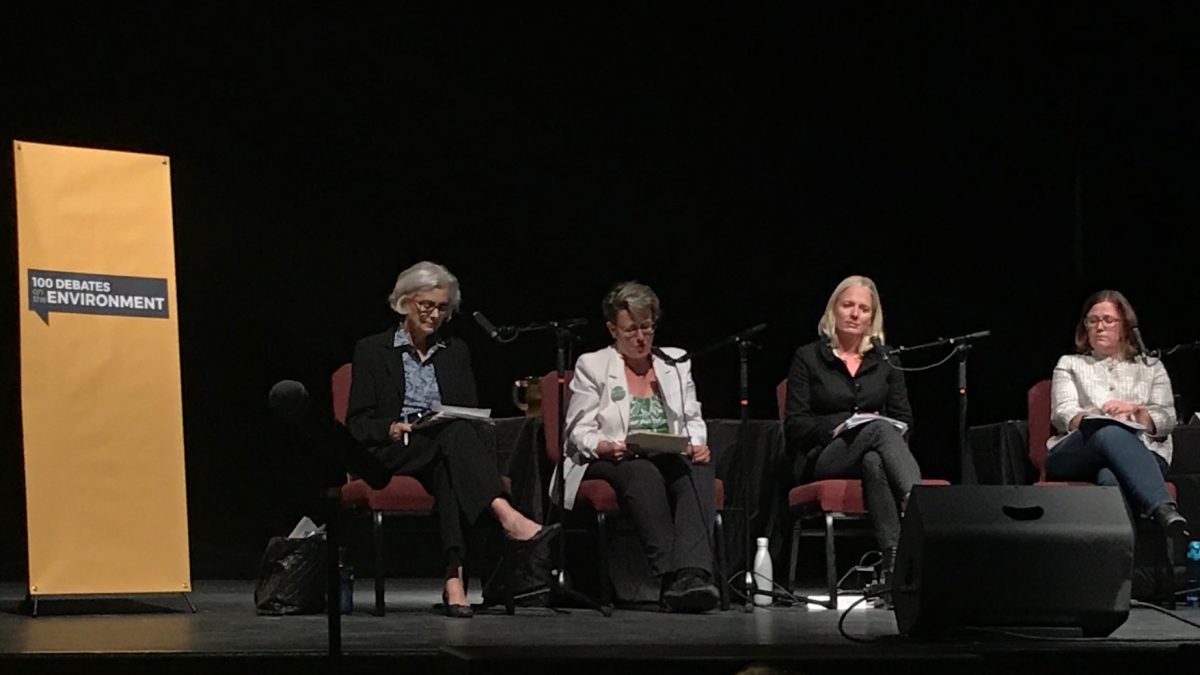

Ottawa Centre’s Liberal incumbent Catherine McKenna — who is also the federal environment minister — was on the defensive during a recent debate on environmental policies as rival candidates and audience members alike attacked her government’s track record ahead of the Oct. 21 election.

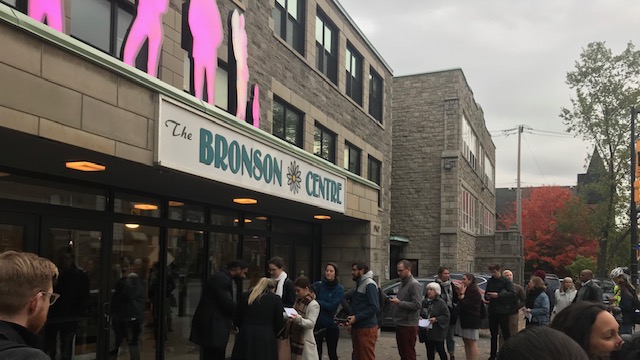

The debate at the Bronson Centre on Oct. 3 was part of 100 Debates on the Environment, an initiative of the environmental advocacy groups GreenPAC and Equiterre to stimulate discussion about climate change during the federal campaign.

McKenna drew sharp criticism when she was asked by a member of Fair Vote Canada, the nation’s leading advocacy agency on electoral reform, about a possible link between Canada’s first-past-the-post electoral system and the ability of any government to take bold climate action.

“I’m very sad that we weren’t able to get it done — that, unfortunately, it was just impossible in Parliament,” she said.

Her response prompted a loud reaction from the audience. “You had a majority government!” one woman shouted.

“We had an electoral town hall and … the people couldn’t even agree on what type of reform they wanted or whether a referendum was needed,” McKenna explained.

At this point, the audience erupted in a flurry of anger.

“I’m not making excuses,” McKenna said, “but I absolutely agree — I wish we weren’t having these fights on climate change. I wish people were able to come together.”

Her explanation garnered mixed reactions from the audience. Some cheered her on while others continued to voice their frustrations. One woman yelled “Shame!”

NDP candidate Emilie Taman and Green candidate Angela Keller-Herzog were each quick to say their respective parties were committed to reforming Canada’s electoral system.

“I’m more than troubled,” said Taman. “I feel betrayed even by this government’s broken promise to change our electoral system to one where every vote counts. I have no doubt that a Parliament that truly reflected the preferences of Canadians would be demanding and delivering much more urgent climate action.”

Conservative Carol Clemenhagen, on the other hand, wouldn’t commit to electoral reform.

Canada’s first-past-the-post electoral system has become a point of contention because it tends to produce governments that do not accurately reflect the popular vote.

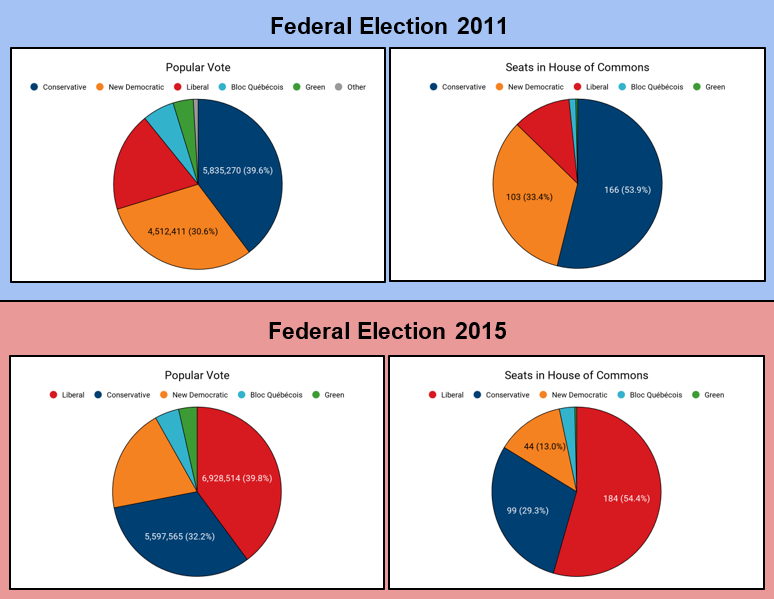

In 2011, Stephen Harper’s Conservatives formed a majority government with less than 40 per cent of the popular vote. In 2015, as a direct response to this, the Liberals promised to change the country’s electoral system.

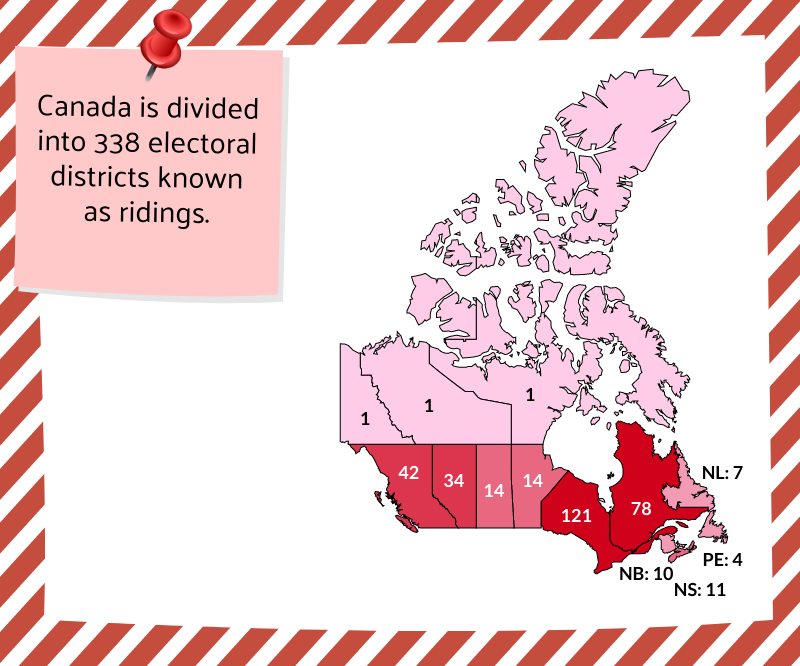

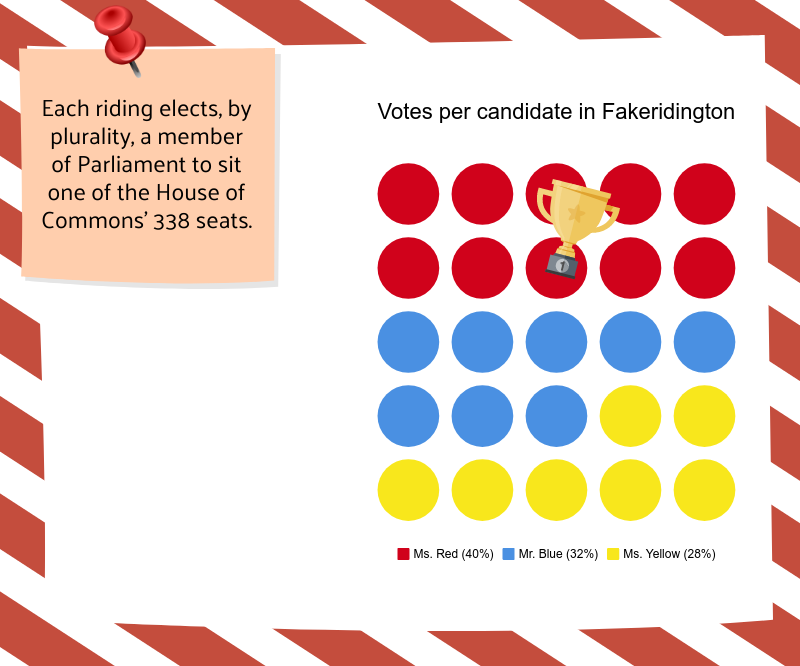

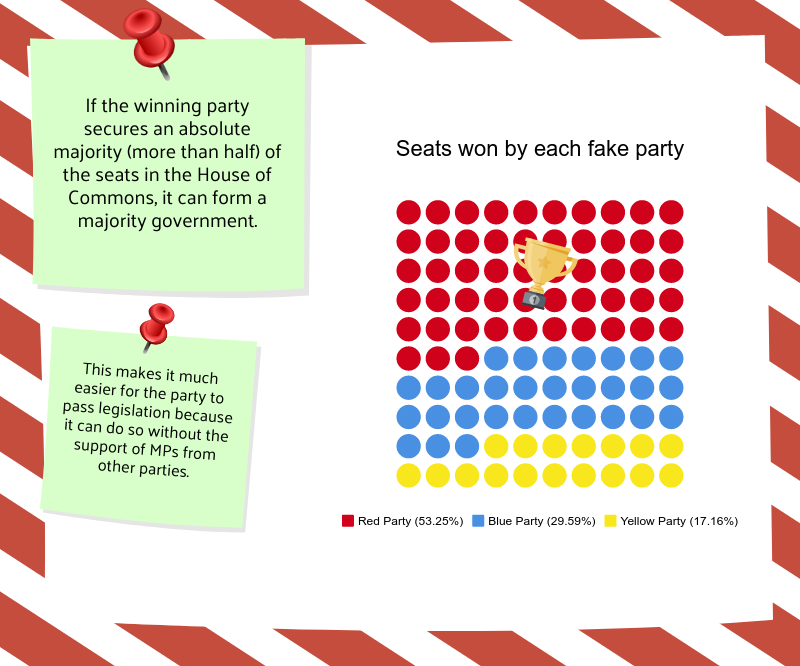

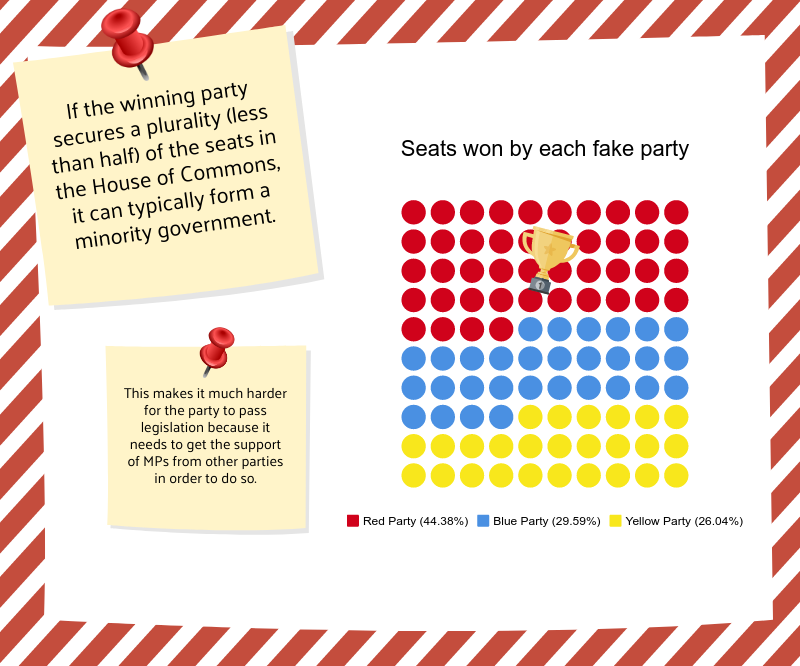

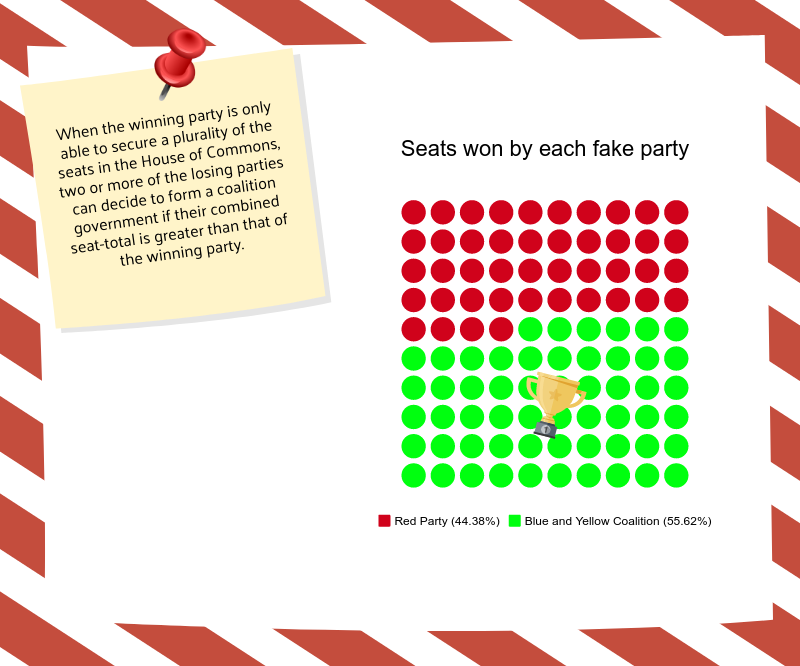

Canada is divided into 338 electoral districts or ridings. Each riding elects one candidate — the highest vote-getter — to serve as its member of Parliament. The party that wins the most seats is then typically able to form government — although in certain minority scenarios, two or more opposition parties representing a majority of seats could strike an accord to govern.

Because each riding elects one MP, however, votes cast for other candidates who do not end up winning have no impact on the number of seats won by each party in the House of Commons .

Several different versions of proportional representation have been proposed as alternatives to Canada’s current system, but each would essentially increase the number of representatives elected at one time in each electoral district.

Under a mixed member proportional electoral system, the system suggested by the Law Commission of Canada in 2004, voters would cast two votes — one for their local MP and another for their regional representatives.

While the vote for a local MP would function in much the same winner-take-all fashion as it does today, the vote for regional representatives would be used to “top-up” the House of Commons so that the number of seats won by each party would be proportional to the number of votes cast in their favour.

This version of proportional representation is practised across the globe in countries such as Germany, New Zealand and Scotland. Other versions include the single transferable vote and rural-urban PR models.