Since 1980 Ottawa farmer John Vandenberg has been growing and selling produce — onions, berries, garlic and more at Rideau Pines Farm in North Gower.

He supplies 25 local restaurants and households in developing suburbs nearby. But for more than 40 years, Vanderburg has watched local farm land, which he describes as some of the best in Canada, disappear.

“There is about a 10th (of the farms) than there used to be,” said Vanderburg, adding that a lot of that prime land has been sold to developers. “Every town around here has got a development going right now,” he said. “[I]t’s getting closer and closer.”

As Ottawa’s council gets ready to vote on an extension of the urban boundary, Ecology Ottawa (and others) are urging the city to keep the boundaries where they are through its Hold-Back-the Line campaign.

The next joint meeting of the Planning Committee and the Agriculture and Rural Affairs Committee is scheduled for May 11, 2020, where the issue will be considered (assuming there are no further delays due to the pandemic).

The idea behind the Hold-The-Line campaign is the creation of more dense areas where people can be closer to the things they need, says Emilie Grenier, Ecology Ottawa’s campaign organizer.

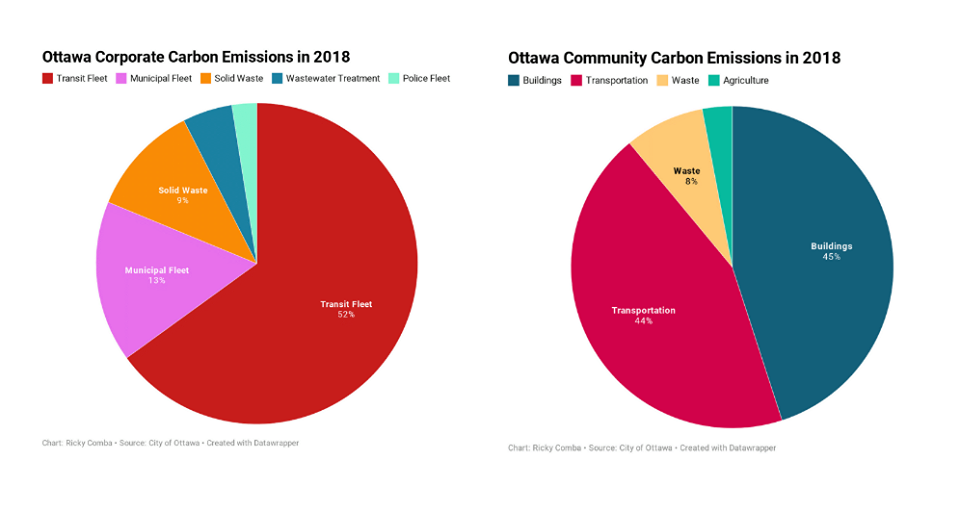

“It’s really an area where you can have access to all the resources you need in a 15-minute walk. Going to the grocery store, day care, and work in a short time,” said Grenier. This results in a greener city with more transit use and lower carbon emissions, she said. Last April the city declared a climate emergency.

In a 2019 report, city staff looked at different scenarios for population growth and density inside the new urban boundary. The city used intensification rates of 50 and 60 per cent. These rates refer to the percentage of new homes built in already serviced areas. To maintain the current boundary would require a 70 per cent intensification rate, meaning 70 per cent of all new homes would have to be built in areas with existing water, sewer and other services.

Campaign supporters are asking for 70 per cent intensification on currently developed land and 30 per cent greenfield development on previously undeveloped land within the current boundary, Grenier said.

One consequence of urban sprawl means greater use of cars and higher transportation costs as the city will need to spend far more to branch into rural landscapes, Grenier explained. “The farther we sprawl the more transit we need.”

Grenier says she is concerned that low-emission transportation, such as Light Rail Transit, is taking far too long to get to suburban neighbourhoods. She added that many residents are losing trust in transit because of the problem-plagued Confederation line.

Andrea Flowers, the consultation manager for the City of Ottawa, agrees. “If we intensify, then yes we do reduce our emissions if we stay on gasoline vehicles,” she said.

However, “if we make the type of transitions (to public transit) that we require to meet our (climate change) targets, it’s not going to make that much of a difference” if the boundary expands, said Flowers, who is leading the city’s renewable energy strategy.

Despite long-term green solutions, Bay Ward Coun. Teresa Kavanagh says the city should focus on intensification efforts. “I fully respect that we should keep our rural lands, rural,” she said.

However, Kavanagh says she recognizes that holding the line on urban sprawl is quite controversial.

While some residents like John Vandenberg and the members of Ecology Ottawa fear the impact of sprawl, those living in urban areas can feel hesitant towards intensification as well, Kavanagh added.

“For people already living here, it is hard on them in terms of getting used to something new, more homes and buildings within the city, and I am aware of that,” she said.

One of her concerns with sprawl is that by using farmland for housing development, Ottawa limits the success of local farmers, like John Vandenberg. “When you turn it into land to use for housing, obviously the price goes skyrocketing and we take away the opportunity to grow food,” she said.