Hearing shouts and screams from a large protest near his Toronto apartment, Josh Chernofsky set off to find out what was going on. He came back a changed man.

When he arrived on the scene that day in May 2019, he saw two groups facing off: one crowd was proudly hoisting Canadian flags in the air, shouting about “protecting Canada.” The other consisted of counter-protesters, dressed in black, swearing and screaming.

He was instantly drawn to the patriotic-seeming crowd: “Everything was very positive-sounding,” he recalled.

That was the day Chernofsky, now 37, began his descent into the far right. He became a member of the Proud Boys, a male-only, white supremacist terrorist group, and attended a number of its protests and meetings, he said.

A few months later, the pandemic struck — a global health crisis that has helped spur the growth of the far-right movement.

RCMP spokeswoman Sgt. Caroline Duval said that groups promoting violent and extremist ideologies have become more active across Canada over the past few years. “The RCMP and its public safety partners remain vigilant for potential threats,” Duval wrote in an email.

The number of Canada’s far-right groups surged to 300 in 2020 — three times what it was in 2015, according to a report by the National Security and Intelligence Committee of Parliamentarians, an independent panel of MPs and senators who review federal intelligence.

The pandemic has been a key contributor to this growth, they reported.

“The pandemic has affected the accessibility of targets, the planning of violent extremists and the radicalization of individuals,” the panel warned. Online, anti-government rhetoric has also increased, something far-right groups have been using as leverage.

The isolation and financial hardships that many have faced because of COVID-related lockdowns have fuelled the anger that far-right groups strive to channel into hate, the report noted. This trend has grown exponentially, as more homebound Canadians turn to their computer screens for information, leading some into “extremist echo chambers,” said the report.

As frustration over the pandemic mounts, the hate fostered by far-right forums online has increasingly spilled into events on the ground. Canadians witnessed this effect during the fall election, when supporters of the People’s Party of Canada — which has been linked to members of the far-right movement — threw gravel at Prime Minister Justin Trudeau at a campaign stop.

Aggressive crowds of anti-vaxxers, many of whom are inspired by far-right conspiracy theories, have harassed healthcare workers and patients at hospitals and vaccination centres across Canada.

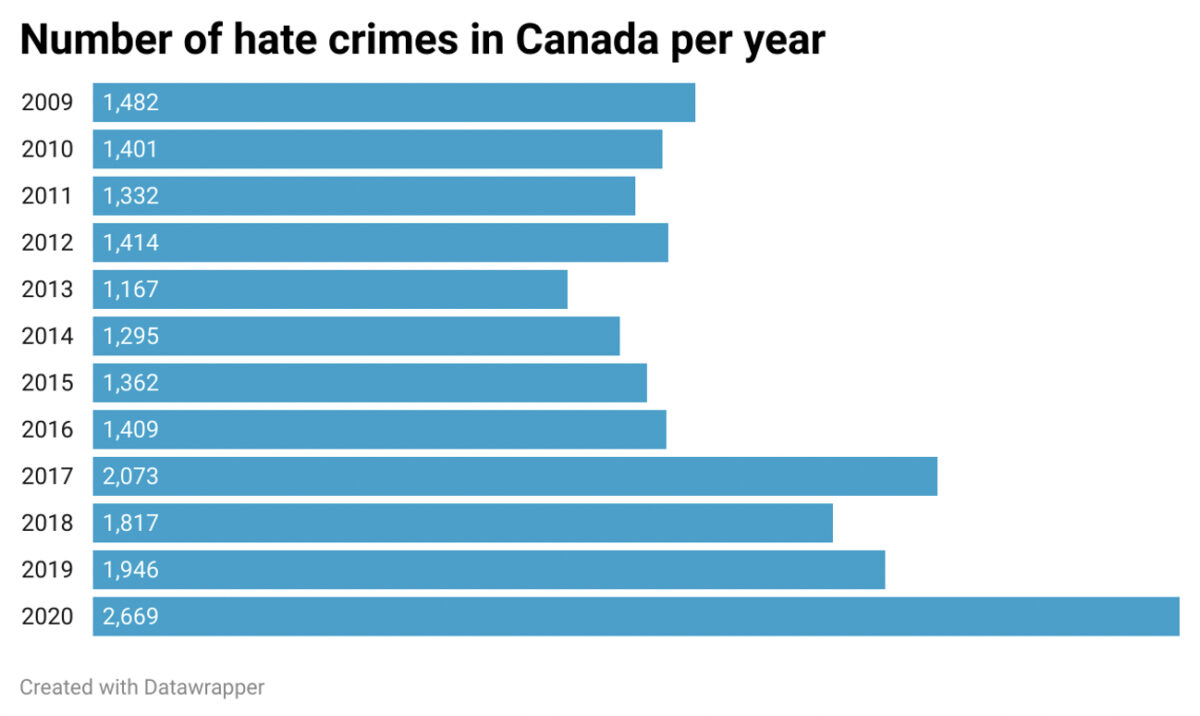

All the while, hate crimes have spiked over the past few years.

The number of police-reported hate crimes in Canada increased by 37 per cent during the first year of the pandemic, rising to 2,669 incidents in 2020 from 1,951 in 2019. This marks the largest number of police-reported hate crimes since comparable data became available in 2009, according to Statistics Canada.

Also in 2020, Toronto police reported a 51-per-cent increase in hate crime reports, according to Global News.

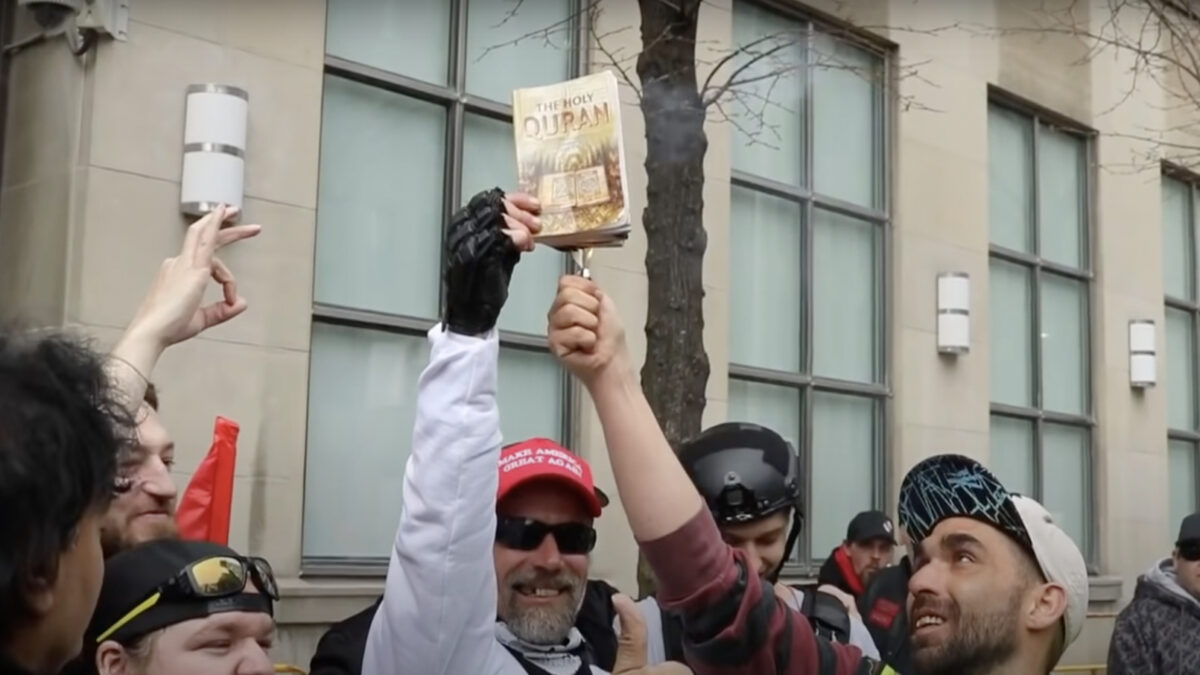

Muslim Canadians are one of the groups most commonly targeted by far-right organizations. Making up just three per cent of the population, Muslim Canadians have accounted for 11.6 per cent of victims of hate crimes reported to police, on average since 2015, according to the National Council of Canadian Muslims.

Anti-Muslim rhetoric has become one of the most popular expressions of right-wing extremism, according to 2020 report by the Institute for Strategic Dialogue, a U.K.-based think tank that studies extremism.

Islamophobia is “more common than we think,” said Fatema Abdalla, the spokeswoman of the NCCM, citing the example of the June 6 attack in which a young, far-right extremist drove his pickup truck into a Muslim family in London, Ont., killing four people.

Mohamed-Aslim Zafis, a volunteer caretaker at a Toronto mosque, was murdered outside the building on Sept. 12, 2020 by a white suspect alleged to have ties to neo-Nazi groups. A month later, another Toronto mosque received death threats, including a warning that an imminent attack would be the next “Christchurch,” referring to the 2019 mass shooting in New Zealand in which a white supremacist killed more than 50 people.

Abdalla added that Muslim women specifically are at greater risk of being victims of Islamaphobic hate crimes. “In the eyes of an attacker, it’s easier to visualize a Muslim woman.”

Women in general are also a prime target for hate groups. Jan van Heuzen, a creator of Ottawa-based Masculinity: under construction — a group of volunteers who promote healthy masculinity — said men in particular are finding themselves drawn into the far right.

The concept of masculinity is rapidly changing, said van Heuzen, and not everyone’s a fan of this. “In our world, there’s a lot of freedom, so a man can decide much more who and what they want to be . . . For a lot of people, that’s a little bit scary.”

Far-right groups offer men easy-to-follow rules, van Heuzen explained, which helps draw them in.

But those same rules have a deeply ingrained sense of misogyny, he added. The parliamentary panel also noted that hatred for women connects many white supremacists, incels — so-called “involuntary celibates” — and other individuals and groups within the broader manosphere.

Van Heuzen also mentioned that incels — who blame women for their celibacy — are strongly aligned with the far right. What’s more, they’ve become a serious threat.

In 2018, Alek Minassian killed 10 pedestrians in Toronto by driving a van into them along a busy sidewalk, later claiming to have been inspired by the incel movement. And in a landmark move in 2020, the RCMP laid terrorism charges against a teen accused of killing a young woman at a Toronto massage parlour, claiming he was motivated by the incel ideology.

Seeking like-minded people and forging a sense of community is another key driver of the far-right movement, said van Heuzen. People are social creatures, and many of those radicalized into far-right groups are just looking for a community to join, he noted.

Having healthy communities and feeling secure in one’s social status can be all it takes to prevent someone from being radicalized, he said.

The far right can grow even in the most unlikely places. Keir Milburn, an author and researcher at the U.K. offices of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation, an education and advocacy organization, points to the “cosmic right” — new-age, spiritual and wellness communities — as a growing concern.

Milburn said these communities have been embracing far-right ideals and conspiracy theories, and the trend has “massively accelerated” during the pandemic.

This is because the pandemic challenges many people’s ideas about what freedom means, explained Milburn. The coronavirus crisis has shown us that we are not as unique as we’d like to think, he said. People may want to feel like their own person, but they also rely on everyone around them.

“That counters a certain way which a lot of people have considered to think of themselves,” said Milburn.

In Canada, one striking example of this trend is Yolande Norris-Clark, a wellness YouTuber who alleges COVID-19 vaccines are an “unknown substance.” In one video, she likens public health restrictions to Nazi Germany.

“Medical mandates today are a major step backwards towards a fascist dictatorship, and genocide,” she says in one video.

Far-right conspiracy theories such as QAnon, which was popularized in the U.S., are quickly becoming a concern in Canada, as well, observers say. Intelligence files from the Canadian Security Intelligence Service, obtained by Global News under the Access to Information Act, report that the QAnon narrative continues to circulate in the Canadian online environment and is often invoked during anti-mask events across the country.

Radio-Quebec, one of the most popular QAnon social media platforms in Canada, is rife with disinformation. For instance, one of its more recent videos claims the new Omicron variant is being used by the Canadian government to keep citizens afraid and under control.

Although the rise of the far right is a growing concern, people shouldn’t panic, according to Phil Gurski, who spent his career surveilling and researching extremists for CSIS.

Gurski agreed the far right is a real threat, but likened the rising concern about right-wing extremism to anxiety about Islamic extremists in the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks in the U.S. in 2001.

There’s a handful of reasons why he doesn’t think the far-right is as dangerous as some may think, Gurski explained.

“The far-right is a dog’s breakfast of ideologies,” Gurski said. Many of their members join for different reasons, making it harder for them to develop a clear set of goals or a consistent ideology, he noted.

Many on the far right also spend most of their time behind a computer screen, Gurski said, and people can’t equate online action to real-world activity.

“The vast majority of these people are incompetent, useless and cowardly, who can’t get off the couch and won’t get off the couch.”

Gurski said the far-right remains a small minority of Canada’s population.

“(The far right) doesn’t define Canada, it doesn’t define Canadians, and it doesn’t define human society, either.”

As for Chernofsky, he said that what got him out of the far right was his own humanity and his crisis of conscience over the death of a former adversary.

During a protest in which the Proud Boys clashed with antifa — an anti-fascist counter-protest group — Chernofsky said he recognized some people at the event, including activist Sarah Hegazi, on the other side of the battle. Some time later, she killed herself, he said.

Chernofsky said he remembers her as someone going head-to-head against men three times her size.

“It really stuck with me, the way people on my side at the time were acting — and celebrating (her death),” he said. “It’s always rubbed me the wrong way, and still to this day I carry a lot of guilt . . . I still feel I have some responsibility for it. I don’t want anyone else to have to deal with that.”