Most people love the warm indoors on cold wintry days. But for many, the season can bring asthma triggers from dust mites, mould, damp and wood smoke. In such situations, the L-shaped aerosol puffers — metered dose inhalers — come to the rescue by making breathing easy.

While this small device might be a life-saver for asthmatics and others with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases (COPD), for the planet these inhalers are bad news.

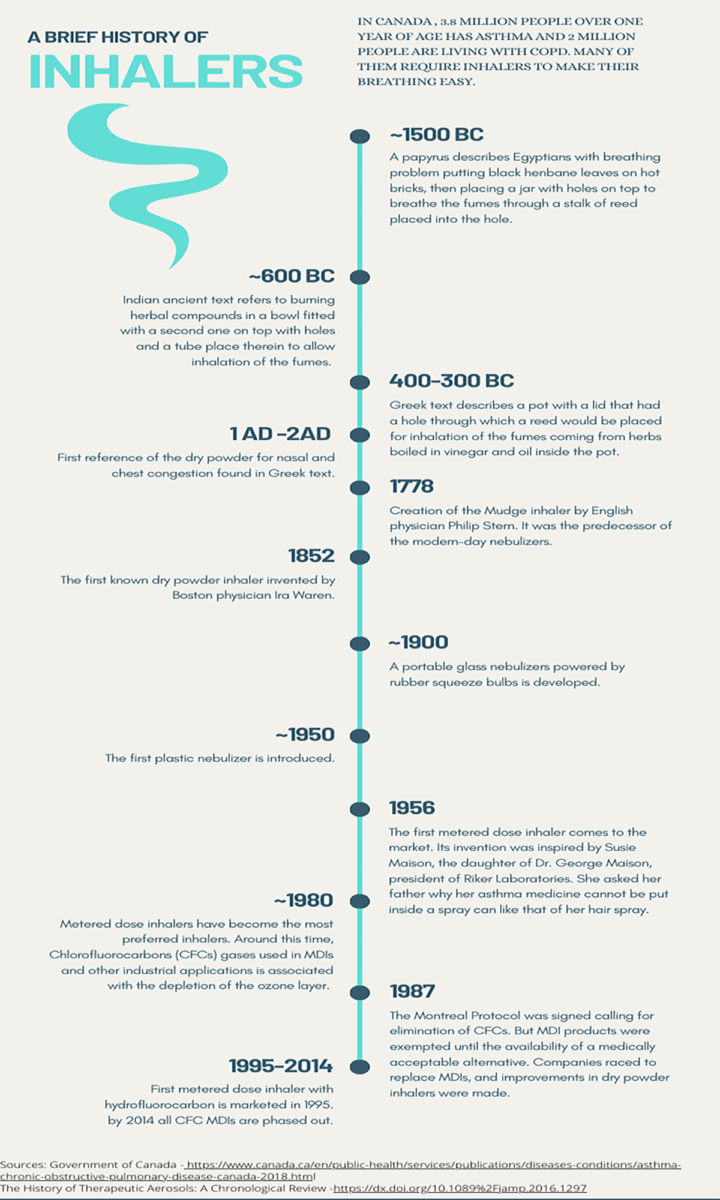

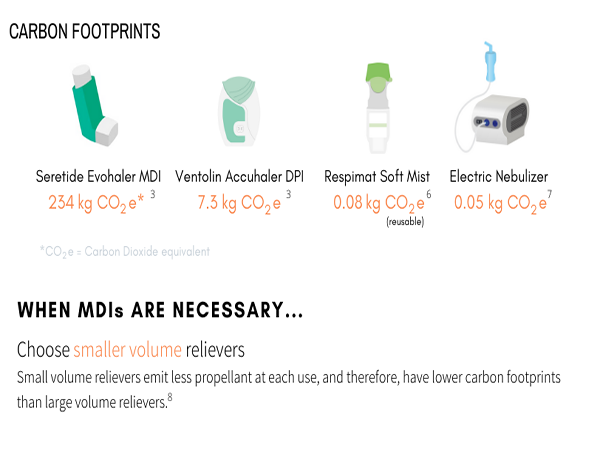

In 2019, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence in the U.K. reported that 100 doses in a metered dose inhaler (MDI) have a carbon footprint equivalent to a 180-mile car journey.

These inhalers use hydrofluorocarbons to propel medication into the lungs of the patients. Depending on the type of hydrofluorocarbons used in the pressurized canister, the gases can have a high global warming potential — 167 to 1,550 times higher than that of carbon dioxide, according to the Centre for Sustainable Health Systems.

The centre, based at the University of Toronto’s Dalla Lana Public School of Health, is calling on primary health clinicians in Canada to prescribe greener alternatives such as dry powder or soft mist inhalers where appropriate.

Since June, the centre has conducted four free webinars on the climate impact of inhalers for primary health-care providers and others interested in the issue. Along with the carbon footprint of individual inhalers, the webinar discussed guidelines and recommendations from the Canadian Thoracic Society on prescriptions and best practices.

Kimberly Wintemute, a family doctor and an assistant professor at U of T, is one of the developers of the webinar. She said the centre’s initiative is creating interest among members of the medical community.

Although research about MDI’s climate impact is not new, Wintemute said getting physicians to change prescribing habits in North America — where the metered dose inhalers have been prescribed the most — is going to take time.

“Usually, what people will prescribe is what they learned in their training,” she said. “So if you learned in your training to prescribe metered dose inhaler, then usually for most of your career, you will continue to prescribe metered dose inhaler.”

Aaron M. Tejani, a pharmacist and a researcher at the University of British Columbia’s Therapeutics Initiative, expressed his skepticism about asking patients to switch from MDIs to dry powder or soft mist inhalers.

Tejani, who attended one of the webinars, pointed out that people with weaker lungs find it hard to use dry powder inhalers since it requires patients to inhale quickly.

Some inhalers other than the MDIs require nimble hands to make them function properly, he adds.

Wintemute agreed. She said young children under the age of five and very frail elderly people will need to continue to use MDIs with a spacer.

“You like to grab, sort of, a very low hanging fruit when you’re going to try to make systemic changes to try to improve the climate — and metered dose may well be a low hanging fruit.”

— Alan Kaplan, chair of Family Physician Airways Group of Canada

Not everyone in the rest of the population of asthmatic and COPD patients can switch to greener alternatives.

Carmela Graziani, who has severe, steroid-resistant asthma, says the dry powder inhalers did not work for her when she used them in the 1990s. Currently, she is using only the metered dose inhalers along with a biologic drug — an antibody, a kind of protein that occurs naturally in the human body.

Wintemute said she recognizes that not all patients — especially those who are seeing a respirologist, usually for severe asthma — would be appropriate for the switch.

“If I’ve asked (a) respirologist to look after (a) patient, I need to let them prescribe how they’re going to prescribe,” she says.

For her own practice, she cites two reasons when sending patients with mild or very mild asthma an invitation to change from aerosol to dry powder inhalers.

“Number one, the guidelines have changed. So, we should no longer be prescribing metered dose inhalers for people with very mild and mild asthma,” she says. “And then number two, that the metered dose inhaler has a very high carbon footprint because the propellant is a potent greenhouse gas.”

The guidelines are those issued by the Canadian Thoracic Society and the Global Initiative for Asthma. They recommend that patients with mild and very mild asthma should use a dry powder inhaler combination of two medicines — budesonide and formoterol — both for reliever and maintenance therapy.

Historically, people would use two separate puffers — the reliever, which provides instant relief when people have asthma attacks, and the maintenance puffer, which contains an anti-inflammatory medicine in the form of a steroid to keep the asthma away, explained Wintemute.

The dry powder inhaler, sold in Canada under the brand name of Symbicort, has both the anti-inflammatory steroid and formoterol, which opens the airways immediately and effectively, she adds.

The inhaler’s manufacturer, AstraZeneca Canada Inc., did not respond to an interview request from Capital Current.

But Alan Kaplan, chair of Family Physician Airways Group of Canada and a member of the medical and scientific advisory committee of Asthma Canada, explained why the dry powder inhaler can solve another concern that physicians have.

He said the aerosol device – MDI — has been used historically to deliver short-acting beta2-agonist (SABA), a type of bronchodilator that relaxes lung muscles and widens airways.

“SABAs in an MDI are the number one prescribed and sold inhalers,” Kaplan said.

But SABAs only treat asthma symptoms, not the disease itself, he said, whereas asthma is primarily a disease of inflammation of the airways.

Research on SABA overuse shows an association with bad outcomes such as exacerbation of symptoms, hospitalizations and even death among people who use more than three SABA canisters per year, said Kaplan.

He cited several studies done in the U.S., Canada and Europe on this issue.

Kaplan said that one solution to the overuse of MDI SABAs could be for patients to use their controller or maintenance puffers more aptly and regularly, thus decreasing their reliance on SABAs for asthma symptoms.

The other solution could be the combination medicine budesonide formoterol approved by Health Canada to be used as a reliever instead of using a SABA.

That would improve the situation in two ways, Kaplan said. “Number one, people have less exacerbations because we’re treating them with inhaled steroid at the time they need it; and number two, it’s a dry powder so we’re not using the MDI, which we recognize is bad for greenhouse gases and the climate.”

Kaplan added: “You like to grab, sort of, a very low hanging fruit when you’re going to try to make systemic changes to try to improve the climate — and metered dose may well be a low hanging fruit.”

Though Graziani cannot make the switch, she said the environmental impact of inhalers is important for her as asthmatics are often sensitive to changes in the environment.

Her concern is more to do with the disposal and recycling of all types of inhalers, since most are made from plastic materials.

“I have not found a lot of information about what happens to these inhalers after I dispose of the canister at the pharmacy and dispose of the plastic sleeve in the blue box,” she said.

“Where do they go? Are any of the materials reclaimed?” she asked, stressing the need to look at the bigger picture rather than just making one small change to address an environmental problem.