It was when Augatnaaq Eccles was attending Nunavut Sivuniksavut, a college program designed for Inuit students to learn more about their culture, that she was first introduced to the dark history of Inuit relationships with tuberculosis sanitoriums.

Starting in the 1940s, more than 5,000 Inuit were sent to one of about 20 tuberculosis treatment centres in the south, where many suffered from abuse under the Canadian government’s tuberculosis program.

“It really blew my mind. For one of our projects (at Nunavut Sivuniksavut), we had to talk to our family members to see if our families had any connections — which is when I found out that my grandmother, uncle and aunt all had spent time in a TB sanitorium,” she said.

Although Eccles was shocked about her own family’s history with sanitoriums, her family members were even more astonished to learn that the letters they had been sending to relatives back home had been opened, translated and filed as part of a surveillance program set in place by the Canadian government.

Through reading an APTN news article and requesting access to the “Eskimo Correspondence Letters” eventually made public through the Access to Information Act, Eccles slowly started to discover the scope of the government surveillance. Eccles was able to read many letters sent from her relatives and others highlighting the abuse that occurred at TB sanitoriums.

“I was finding letters from my own family members that I wasn’t expecting to find, but I felt like it was work that had to be done,” she said. “It is a really sensitive subject because we didn’t know these letters existed and that they were recorded.”

Eccles said she originally thought of the idea to connect TB sanitoriums to the parka she was making for her course as many Inuit made art in TB sanitoriums to support themselves during their stays in the treatment facilities, including Eccles’ grandmother.

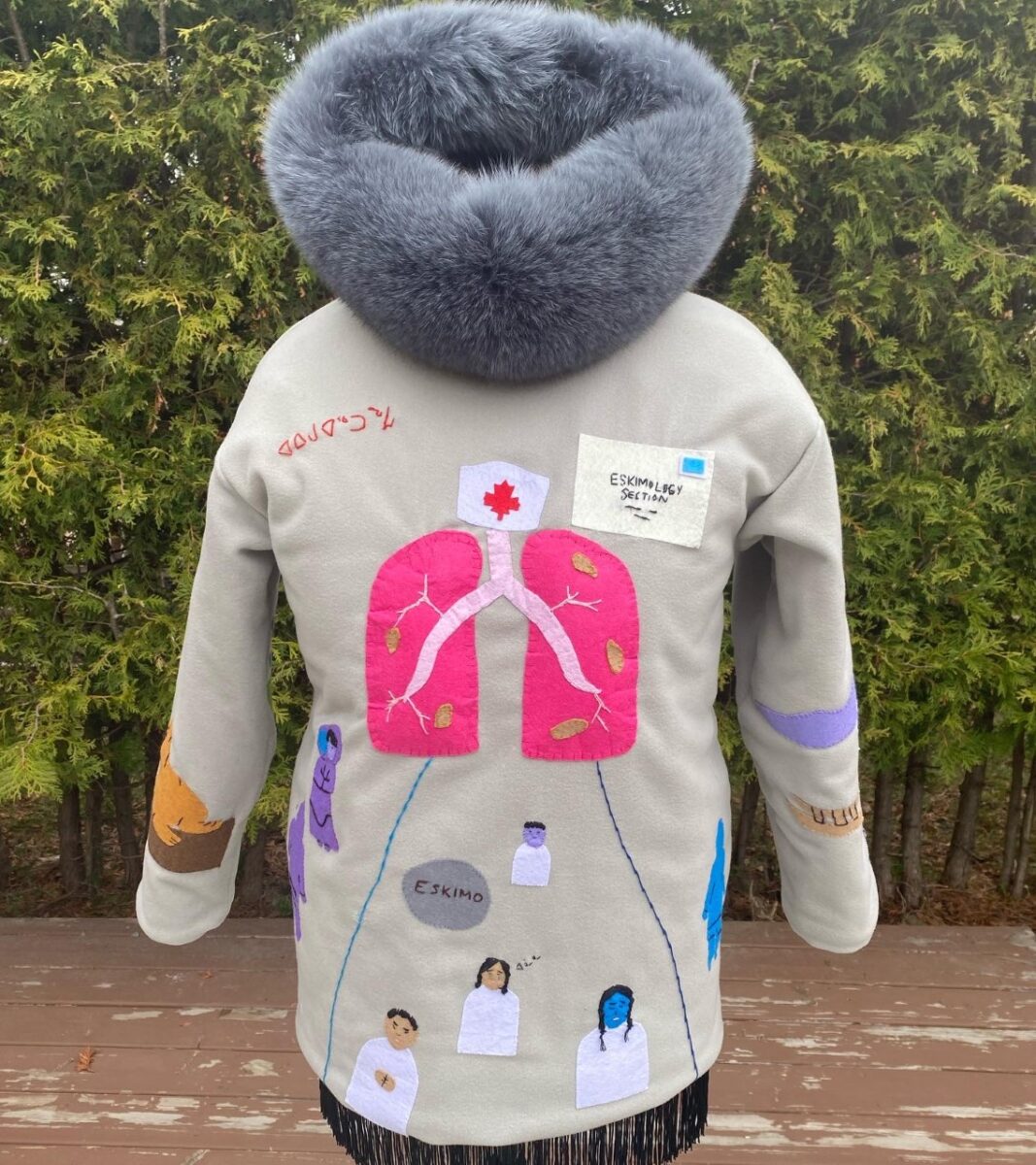

Today Eccles’ tuberculosis parka features symbols of some of the hardships that Inuit went through at the sanitoriums and is modelled on traditional Inuit wall hangings. Scenes portrayed on the parka include a pair of tuberculosis-affected lungs attached to a nurse’s cap embroidered with a Canada flag to represent the medical system. There are also images of a documented letter and of the Artic summer and winter, representing the seasons at home that Inuit missed while away at TB sanitoriums.

Toward the bottom of the parka Eccles included a stone with the word “Eskimo”. She said that during the project, she found out that there are dozens of graves simply labelled with the word “Eskimo” or “Indian” all over Canada. These sites hold the remains of Inuit victims of tuberculosis buried in unmarked graves after passing away at TB sanitoriums.

At the bottom of the parka Eccles included other elements symbolizing family tragedies and loss of culture.

“Coming back from TB sanitoriums, children did not recognize biological parents and children who were away were not able to communicate with their families because they forgot the language,” said Eccles. “There is this sense of displacement. It continues today.”

Eccles said she was surprised when she was approached by Dawn Setford (Mary Francis Whiteman), Iehstoseranón:nha (She Keeps the Feathers), the founder and president of the Indigenous Women’s Art Collective, to present her tuberculosis parka as part of this year’s Orange Shirt Day activities on Parliament Hill.

“I think that bringing this piece to Parliament is a great way to get the message out about this history. I hope it brings a sense of compassion and understanding towards this part of our history, and art is such an important way to get the conversation going,” Eccles said.

Eccles’ creation it is displayed on Parliament Hill today and will then be moved into a commemorative showcase at the Canadian Museum of History from Oct. 14-16.

“This wasn’t a long time ago,” said Eccles. “A lot of people who went to TB sanitoriums are still alive and generations of people and loved ones are still being affected today. It’s tough, especially having that family connection — and it’s tough knowing that this is a forgotten piece of history that still affects people and families today.”