Local mental health advocates say they are planning to unveil Canada’s first research-based clinic for first responders.

The move follows the suicide of Const. Thomas Roberts took his life at the Elgin Street headquarters of Ottawa police on Sept. 27. He leaves behind a wife and a nine-month-old child.

His death occurred two days before the annual memorial on Parliament Hill that honours police officers who have died, and five days before Ontario’s chief coroner published a report addressing the deaths by suicide of nine Ontario officers in 2018.

“For several years, we have worked to improve our wellness supports and services to members,” Deputy Chief Steve Bell said in a statement about Roberts’ death issued on Sept 28. “But today, we are all asking questions about why this happened and we know that we have to do more.”

The University of Ottawa and The Ottawa Hospital are creating a research-based mental health clinic for first responders, to support police officers, firefighters and paramedics in Ottawa. This will be the first of its kind in the country.

The first phase of the study, which launched in June, involves interviews with local first responders to understand how they would want to access mental health care. The co-principal investigator, Valerie Testa, said the interviews are intended to highlight what barriers exist.

“It’s been a lot of listening to what their concerns are and then shaping that into research questions and studies,” she said. “If health services are informed by the people who are using them, then they are much more likely to use those services when they are put in place because the services are then acceptable, accessible and feasibly designed.”

By the end of 2019, Testa said she expects phase two of the project will be underway. This will include a first responder operational stress injury clinic through The Ottawa Hospital.

“There is room for 40 individuals, but if more need to seek care, there are clinical services running parallel to this study,” she added.

It is not just this study that is aiming to improve mental health services for first responders. The Ottawa Police Service has offered a peer support group since July 2018, according to Angela Slobodian, the OPS acting director of wellness, health and safety.

“Peer support is all about people sharing what their lived experience is and hopes to help others going through something similar,” said Slobodian, adding that the program consists of 37 peer supporters, including active and retired police officers, along with family members.

Like the research study, the peer support group program has been successful because it has incorporated feedback from police officers themselves, Slobodian said.

“Our peer support program has been built from the ground up,” she explained. “We found out from our people what they want from a peer support program, so there’s been much success because of that.”

The number of officers dying by suicide in the province has gotten the attention of Ontario’s chief coroner, Dr. Dirk Huyer, who launched a review of police suicides in Ontario after eight active and one retired police officer died by suicide in 2018. His report was released to the public on Oct. 2.

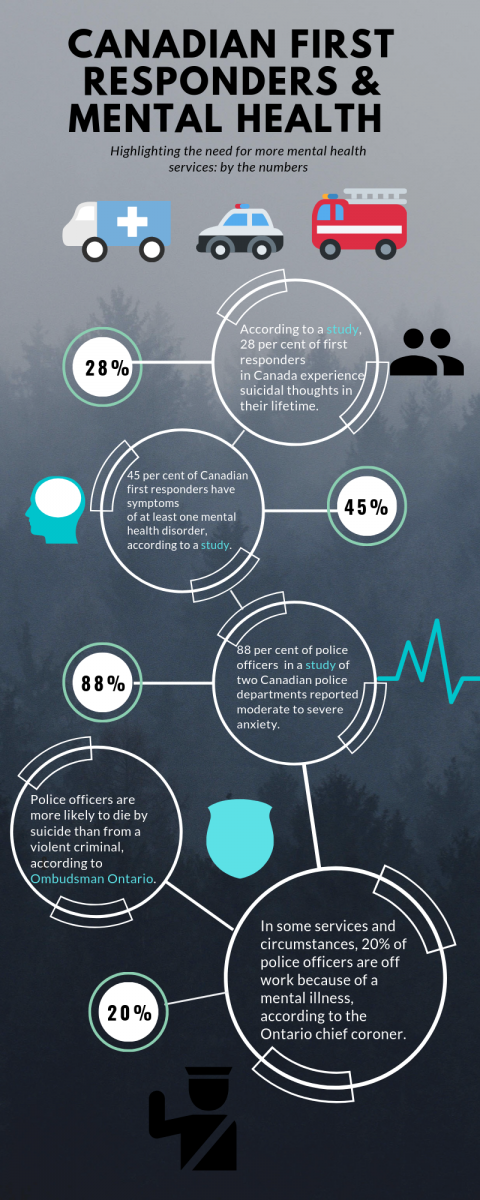

“What we are seeing (with police officers) is increasing challenges with work, increasing responsibility, increasing accountability and increasing problems with those they serve,” Huyer said in an interview, adding that there has been a notable increase in officers who are on leave because of mental illnesses in the province.

“(These reviews) are not a regular occurrence,” Huyer added. “It’s something that is pretty significant when we do it, and it’s usually a topic where there are a number of deaths involving an issue that reaches across many systems.”

Moving forward, Huyer agreed that a collaborative approach in helping officers access appropriate mental health services is essential. The report called for quality care across the province that extends to include “trauma-informed clinicians and the application of evidence-based treatments and solutions,” along with six other recommendations.

So far, Testa said she is pleased about the number of people who are determined to help officers in Ottawa, and she said she’s excited to help lead the research study set to begin in the new year.

“My hope for the future is to do as much as we possibly can to have earlier intervention so that people aren’t seeking services when they are really in crisis,” she said. “(And) that we can have services that are supported by research and then put into practice into the healthcare system.”