By Martin Boyce, Kira Locken and Olivia Robinson

For many, the hot topics of Ottawa’s municipal election include LRT delays, potholes and a proposed plan for a 65-storey building. It’s what the candidates aren’t talking about that has some voters concerned: issues affecting Indigenous Peoples.

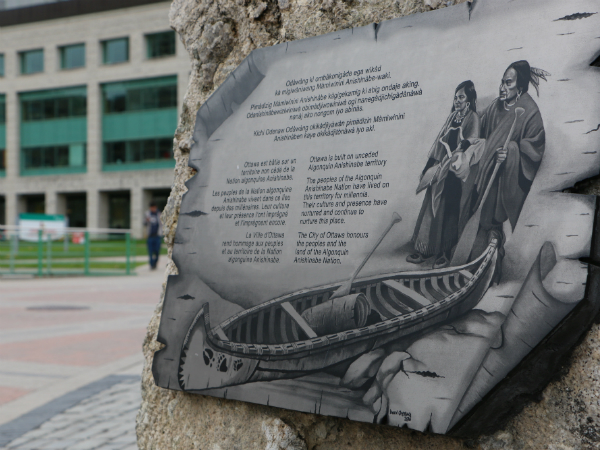

Ottawa is located on the traditional, unceded territories of the Algonquin Anishinabe Nation and is also home to a rapidly growing Indigenous population. According to Statistics Canada, in 2016 22,960 people in Ottawa identified as Indigenous — up from 19,200 in 2011.

Some voters are concerned that, despite the growing population, there’s little discussion at the municipal level of systemic racism; intergenerational trauma and the impact of the residential school system on homelessness; access to justice and child-welfare issues affecting Indigenous people in urban centres like Ottawa. There also continues to be divisive conversations about land developments on traditional Algonquin territory – such as the Zibi condominium project on the old E.B. Eddy property.

Although there has been no mayoral debate dedicated solely to Indigenous issues, Now What?! Ottawa organized a debate on gender-based municipal issues on Oct. 2. After the event, some voters took to Twitter to raise concerns about the candidates’ lack of understanding about Indigenous issues.

“We’re so used to being reactive instead of proactive that when it comes to Indigenous issues in the city, that’s just how we are,” says Jolene Saulis Dione. She is an Indigenous woman who has lived in Ottawa for 20 years and has ties to Tobique First Nation in New Brunswick.

Saulis Dione says London, Ont.-mayoral candidate Tanya Park was recently one of the first candidates to note the need for four levels of government – municipal, provincial, federal and Indigenous – to work together and address complex issues like mental health and addiction.

“What people don’t understand is that reconciliation is just a process, it’s not an actual outcome. Forgiveness is an outcome. First Nations people – they’re ready to talk now. They’re ready to tell their story.”

Jolene Saulis Dione, Kanata North Ward resident

In Kanata North Ward, five candidates are vying to replace Coun. Marianne Wilkinson, who is not running again. Saulis Dione says the conversation at a recent debate was centred on traffic and driving speeds, and that only one candidate, Lorne Neufeldt, spoke about the need for diversity in Kanata North at an all candidates’ meeting.

She says that, despite the city’s approval of a Truth and Reconciliation Action Plan in February 2018, candidates haven’t made reconciliation or issues affecting Indigenous Peoples a priority in their platforms. The plan cites 14 “actionable items,” some of which have completed, such as raising Indigenous flags. The items fall under four categories: culture, employment, children’s services and education and awareness training.

Ottawa is not alone in seeing a growing Indigenous population. Statistics Canada says the Indigenous population in Canada is estimated to exceed 2.5 million in the next 20 years.

Jim Watson, who is running for re-election as mayor, declined an interview on Indigenous issues, but in an email, campaign spokesperson Livia Belcea listed the city’s most “recent reconciliation efforts,” such as the permanent raising of the flags of the Algonquin Anishinabeg Nation Tribal Council and the Algonquins of Pikwakanagan First Nation in June 2018.

Clive Doucet, who is running against Watson, did not respond to requests for an interview on Indigenous issues. Bernard Couchman, another mayoral candidate, stated he would create an “Indigenous action team to mediate the transition over from Crown lands to the Algonquin and other tribes’ peoples,” in his platform, but declined to be interviewed.

“What people don’t understand is that reconciliation is just a process, it’s not an actual outcome. Forgiveness is an outcome,” says Saulis Dione. “First Nations people – they’re ready to talk now. They’re ready to tell their story.”

In the last 10 years, the city says it has consulted with Indigenous Peoples through the city’s Aboriginal Working Committee, which seeks to improve city services for Ottawa’s Indigenous population.

Clara Freire, a manager with the City of Ottawa’s social services department, says the city’s greatest success so far was approving its Truth and Reconciliation Action Plan.

Freire says that an Indigenous e-learning module is being developed to give city staff a better understanding of First Nation, Métis and Inuit populations, land history of Ottawa and residential school history.

Land acknowledgements, considered to be a formal acknowledgement of the traditional Indigenous territories, are slowly being implemented throughout the city, however Freire says there is no official procedure or standardization of land acknowledgements at city meetings.

“Personally, it’s gratifying,” says Freire. “It’s an honour for me to work on this file and to have the partnerships and relationships that I do with members of the community. It makes me very proud that as a city we are taking very seriously to responding to the TRC’s calls to action.”

“There are two things that I always say when it comes to Indigenous issues: It’s great that we have the calls to reconciliate, calls to action, that we have the process of reconciliation, but the only way we’re going to get there is that if we make people uncomfortable and we challenge their thoughts.”

Jolene Saulis Dione, Kanata North Ward resident

Just last year, Watson and city staff were criticized for a new playground at Mooney’s Bay that featured totem poles and chuckwagons – leading some Ottawa residents as well as Indigenous activists to criticize the project for its cultural insensitivity and unclear consultation process.

Saulis Dione believes there are three main issues to watch around Indigenous Peoples in municipal politics in Ottawa: a growing Indigenous population, continued relationship-building with the city, and young people to carry the conversation forward.

“There are two things that I always say when it comes to Indigenous issues: It’s great that we have the calls to reconcile, calls to action, that we have the process of reconciliation, but the only way we’re going to get there is that if we make people uncomfortable and we challenge their thoughts.”