The Ottawa International Animation Festival held its first screening since the start of the pandemic on Oct. 3, featuring some of the best Canadian animated shorts developed over the last few years.

On the bill was the award-winning The Shaman’s Apprentice. In the wake of the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, the screening was an important way to bolster Indigenous voices and stories in Canada.

The OIAF showcased a variety of animated shorts, music videos, and stop-motion styles. Despite the social distance measures taken by in the ByTowne Cinema, the range of stories, from dark, thoughtful dramas to comedically endearing commentaries, left the safely dispersed audience gasping and chuckling in unison.

Various directors, producers, and animators were present, including Ian Keketu (director of Jollof Rice), Mawrgan Shaw (director of Forgotten), Terril Calder (director of Meneath: The Hidden Island of Ethics). Many of the short films were creations by Black and Indigenous animators, each with its own unique message.

One of the most noteworthy shorts featured at the screening was Angakuksajaujuq: The Shaman’s Apprentice, a 20-minute short that has won the FIPRESCI award and TIFF’s Best Canadian Short Film award since its launch earlier this year. It was directed by noted Canadian Inuk filmmaker, Zacharias Kunuk, best known for Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner (winner of the Camera d’or in 2001) and One Day in the Life of Noah Piugattuk.

Kunuk’s newest film is an evocative stop-motion animation that adapts a traditional Inuit story from the North Baffin region. It follows a young shaman in training who must venture on her first journey into the underground to visit Kannaaluk, The One Below, to learn why a member of a nearby tribe has become sick. Accompanied by her grandmother and mentor, the young apprentice faces shadowy spirits and dark, rocky inclines in a quest to save her first patient while learning to harness her fears.

“In the Inuit culture, long before the Europeans came, we have heard stories of how they would heal the sick in the time of Shamans and (help) spirits that rule the land,” Kunuk said in a video statement shown at the festival.

He explained that in the law of nature and rules of taboos, a human being becomes sick when they break a taboo and must confess their wrongdoing. Just as the film shows, illnesses can persist because of a person’s shame over their actions and their desire to hide what they’ve done — in this case, breaking the taboo of sharing.

“We only hear about shamans and what they did a little bit because, in the last 100 years, Christianity has bulldozed over our culture and beliefs,” Kunuk said. “Now we want to … (get) this film out and people can start talking. This is just one story, there’s so many stories out there.”

View this post on Instagram

Being able to watch the animation screening in person was special not only to the guests in the audience, but to crew members who worked on the film as well. Photographed above are the animation crew members who made an appearance to view the event in person after months of being limited to virtual screenings.

“It was something about being side by side and seeing it bigger than your laptop screen that was really lovely,” said Meaghan Hettler, a Sheridan College intern and assistant animator on the Kunuk film. “I missed that from film festivals.”

Sheridan classmate Corrine Roy also worked as an animator and set fabricator. She echoed Hettler’s sentiments about attending the festival in person.

Roy described the uniqueness of Indigenous storytelling in that it follows a non-traditional plot structure.

“There’s like an open-endedness of editing,” Roy said. “It’s an interesting way of seeing that different cultures tell stories differently. It has a lot of implications and things that are left unsaid.”

Having worked on the film since March 2020, Hettler and Roy reflected on the importance of producing more stories for public consumption that better reflect Canada’s diversity.

“None of us are First Nations, but we’re just the hands helping them tell their story in a medium that they really don’t have access to,” Hettler said. “That’s our purpose, is doing the work so that they can tell their stories.”

”The big one for me is just recognizing how many iterations of Little Red Riding Hood or Cinderella have you seen in your life?” said Roy. “There’s so many cultures with so many interesting fables and folklore and stories. We should get more of that in general.”

Canadians have begun to demand increased diversity on their screens. As the country’s most diverse generation yet, members of Gen Z — those aged 14 to 22 — in particular are looking for a wider variety of people to be reflected on their screens, according to a 2019 survey of 500 Gen Z Canadians conducted by VICE and Ontario Creates, the provincial arts-and-culture development agency.

The study showed that Gen Z Canadians are looking for global stories compared to older Millennials, who are more likely to be looking for Canadian creators. Seventy five per cent of Gen Z respondents said that original content is important to them, while 50 per cent said the industry is lacking diverse representation.

According to the report, “diversity is a requirement for Gen Z audiences — in terms of both who is creating and who is being depicted.”

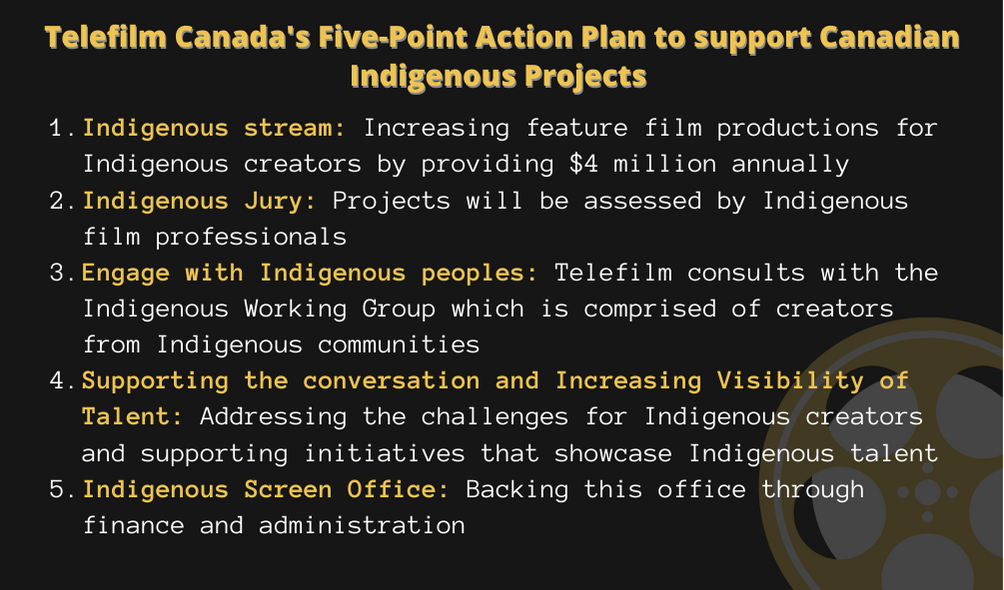

In 2019-2020, Telefilm Canada contributed $4.3 million to 21 projects led by Indigenous creators through the agency’s Development and Production Program. The program has grown significantly from 14 to 23 projects since its launch in 2017.

As the sponsor of the OIAF animation screening, Telefilm’s investments in Indigenous filmmaking and supporting diverse representation generally in the industry allows more creators to share unique perspectives and gain a wider reach among audiences across the country.

Currently, there are 189 employees at Telefilm with 20 per cent identifying as racialized individuals and one per cent as Indigenous. The organization is developing a position that will focus exclusively on improving inclusion and diversity within the agency.

After pledging $100,000 a year towards the Black Screen Office, Telefilm Canada has shown its commitment to creating more access for under-represented and disadvantaged communities. And it’s not the only Canadian organization to increase funding for BIPOC creators in the past year. The Canadian Media Fund also pledged $7.6 million to 13 Indigenous-led projects in 2020, along with Bell Media’s recent partnership with BIPOC TV & Film.

With Canadian organizations increasing funding and visibility for BIPOC stories, and with The Shaman’s Apprentice jointly produced by Kingulliit Productions as well as Taqqut Productions, the outlook for Indigenous-owned media companies is promising. After The Shaman’s Apprentice was recently declared eligibile for an Oscar nomination, Indigenous content creators are paving the way for their traditional stories to finally be retold for wider audiences.