A federal engineer involved in the controversial plan to replace the Alexandra Bridge between Ottawa and Gatineau told a Heritage Ottawa lecture audience that the structure is “at the end of its service life.”

Paul Lebrun, chief engineer at Public Services and Procurement Canada, gave the public lecture on Wednesday. Titled “The Concerns and Challenges of the Alexandra Bridge: PSPC’s Perspective,” the online presentation was part of a series hosted by Heritage Ottawa, the local architectural conservation advocacy group that has also led opposition to the bridge replacement.

Lebrun outlined 12 concerns about the bridge’s poor physical condition and increasing deterioration. He said that the structural and functional ratings of the Alexandra Bridge are considered “inadequate” according to the PSPC Bridge Inspection Manual. This corresponds to a score of two out of six, and PSPC aims for a score of four or higher for its bridges.

“It wasn’t an easy decision for PSPC to move forward with the replacement of the bridge. People within PSPC are as attached to the bridge as people outside of PSPC. However, we knew the bridge was at the end of its service life.”

— Paul Lebrun, chief engineer, Public Services and Procurement Canada

Isabelle Deslandes, the director general of infrastructure asset management at PSPC, started spoke to the crowd in attendance saying, “since the replacement was announced in 2019, community and heritage groups and some members of the public have contacted elected officials requesting that government reconsider this position on the future of the bridge.

“We’ve heard your messages,” she added, “and this is why, when Heritage Ottawa reached out to us, we welcomed the opportunity to join you this evening.”

“It wasn’t an easy decision for PSPC to move forward with the replacement of the bridge,” Lebrun said. “People within PSPC are as attached to the bridge as people outside of PSPC. However, we knew the bridge was at the end of its service life, the feasibility of maintaining it was questionable, and we needed to address the many risks associated with its condition.”

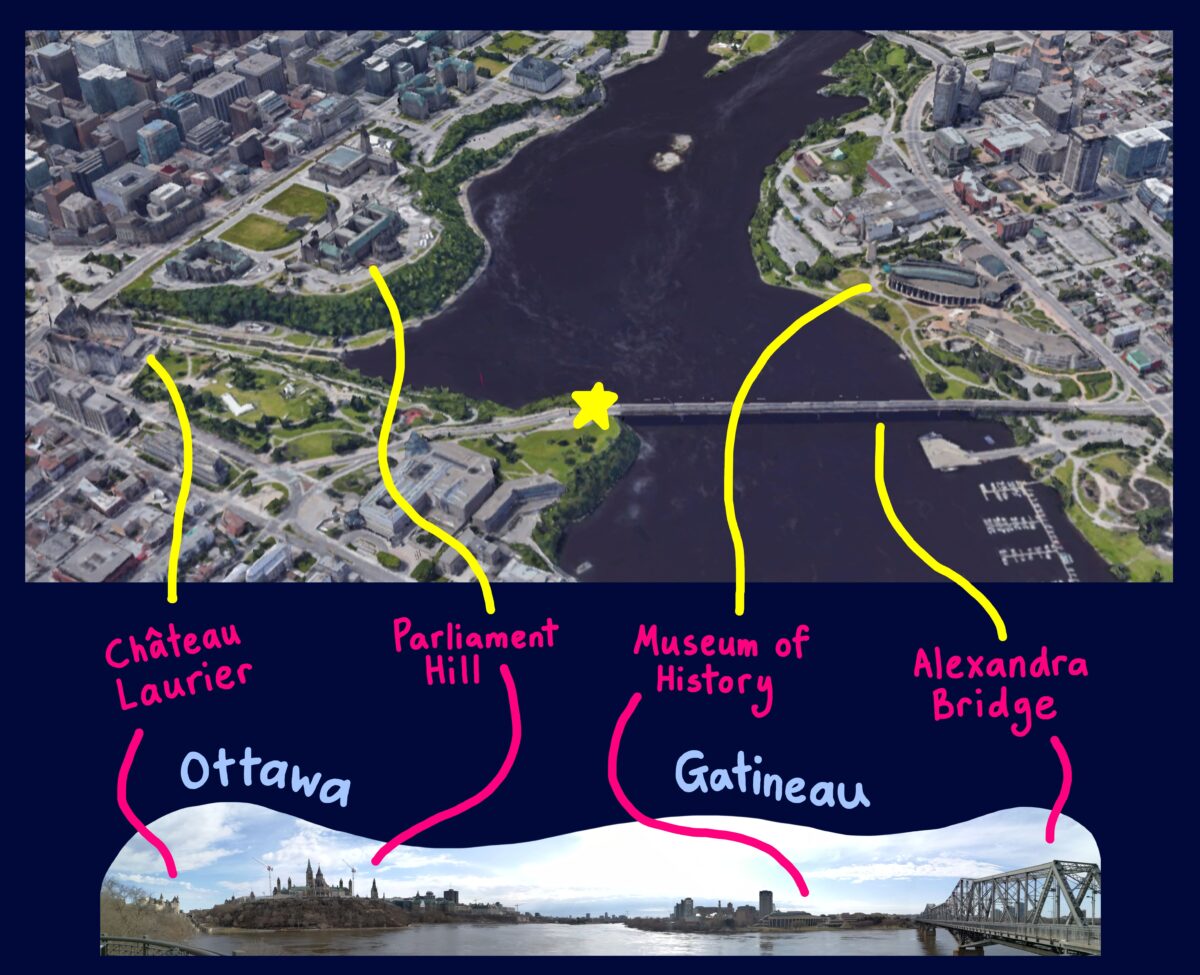

The Alexandra Bridge, also called the Interprovincial Bridge, was named in honour of Queen Alexandra of Denmark, who was married to King Edward VII.

When it opened in February 1901, Queen Victoria had just died, Wilfrid Laurier was prime minister of Canada and there was a mountain of sawdust at the bottom of the Ottawa River.

The bridge was built as a railway connection allowing access to Ottawa from Quebec. Because of the sawdust, the designers decided to make a cantilever bridge, which contains a section that does not require supports in the middle. At the time it was completed, the distance spanned by the cantilevered section was the longest in Canada and the fourth-longest in the world.

Today, the Alexandra Bridge is owned by the federal government and it is regularly used by pedestrians, cyclists and motorists crossing between Ottawa and Gatineau. Two national museums are nearby: the National Gallery of Canada on the Ottawa side and the Canadian Museum of History in Gatineau.

In a 2018 analysis, Public Services and Procurement Canada found that “replacing the bridge would be less disruptive to the public than trying to maintain it,” and that “it would be more cost-effective to replace the bridge than continue to maintain it.”

The 2019 federal budget announced that the bridge would be replaced. The National Capital Commission says that the replacement bridge would be designed and constructed between 2025 and 2032.

Katherine Spencer-Ross, chair of the Heritage Ottawa lecture series, said Lebrun’s presentation is the second the group has hosted about the Alexandra Bridge and is a subject of intense interest among members of the heritage conservation group.

At the first lecture in September, speakers David Jeanes and John Zvonar discussed the history of the bridge and the international context of bridge conservation.

“It’s a very pertinent and in some cases quite an emotional subject for people. Because there’s the big boardwalk on it, we’re used to riding our bikes, and we’re used to walking on it,” Spencer-Ross said.

“We think it’s fair to present all the different sides of the argument. We’re going to listen to what the government plan is because we can’t say one way or another that it’s a good plan or a bad plan until we hear that plan,” she added.

Heritage Ottawa is part of the Alexandra Bridge Coalition, which has attracted supporters from across the country who oppose replacement.

One option the coalition favours involves incorporating a refurbished bridge into a proposed tramway loop between Gatineau and Ottawa, allowing better access between the cities and promoting tourism.

“We are hoping that the bridge is in sufficient condition to continue in an ongoing basis to support active transportation,” said Leslie Maitland, a member of the Alexandra Bridge Coalition and a past president of Heritage Ottawa. “The bridge is going to stay in place for some eight to 10 more years. So we’re thinking, if it can last for eight to 10 more years, can it last longer?”

“If the bridge can be retained, then there’s a significant cost saving and also a significant retention of the embodied energy that the bridge represents. All the energy that went into making those steel girders and erecting those pylons — that is all lost if it’s demolished and goes for scrap.”

— Leslie Maitland, past president, Heritage Ottawa

The coalition believes that keeping the bridge would have significant economic and environmental benefits.

“The greenest bridge is the one that’s already there. It’s going to cost upwards of $500 million to demolish the existing bridge, and hundreds of millions to build a new bridge in its place,” said Maitland.

“If the bridge can be retained, then there’s a significant cost saving and also a significant retention of the embodied energy that the bridge represents. All the energy that went into making those steel girders and erecting those pylons — that is all lost if it’s demolished and goes for scrap.”

Heritage Ottawa is planning another lecture this fall about possibilities for green transportation on the Alexandra Bridge. Next year, the organization plans to host a fourth lecture that summarizes the first three in French.

The federal government has said in an announcement about a public input process that ends April 24 that “the new bridge would support vehicular traffic (two lanes), active transportation (one lane), and public transit (one lane).”

Spencer-Ross said Heritage Ottawa anticipated that Lebrun’s lecture — held via Zoom — would attract people from all around the world. Since the pandemic, Heritage Ottawa has hosted its monthly lectures online and made the recordings publicly available.