Volunteer-led activities in prisons across Canada have been shut down because of the pandemic, making already-difficult conditions worse and adding to the strain on inmates’ mental health, advocates say.

“Just like anyone else in society, they’re terrified for their own health,” said Murray Fallis, the public interest articling fellow for the John Howard Society of Canada. “And then in addition to that, they’re in a prison.”

Being incarcerated makes someone more vulnerable to COVID-19, said Fallis, because of poor ventilation and inmates living in close quarters. However, the ramifications for prisoners’ mental health haven’t fully been considered, he said.

“Lots of these individuals who already have mental health issues are now struggling anew,” Fallis said.

To prevent the spread of COVID-19, some prisons have kept inmates in their cells with no access to outdoor exercise, showers or phones to call their families or legal representation. And the Correctional Service of Canada said that, as of Dec. 16, it was suspending in-person visits in all its Ontario institutions “in the interest of the health and safety of the public, our employees, inmates, and their families.”

Among other problems, said Fallis, volunteer groups can’t get access to large spaces in institutions, such as gyms, to gather safely in a physically distanced manner.

Volunteer groups can include book clubs, the self-help 7th Step Society, narcotics and alcohol abuse support groups, “lifers” groups for inmates facing life in prison, and various religious groups.

Activities help rehabilitation

Prisons may punish people and hold them accountable for their actions, but their fundamental purpose is to rehabilitate the inmates, said Fallis, and participating in activities plays a key role.

“It really teaches them the fundamental core skills that they would require to successfully reintegrate into society,” said Fallis.

Books 2 Prisoners (B2P) – an Ottawa-based volunteer group – donates books to inmates in Ontario, Alberta, British Columbia, Quebec, California and Texas. Volunteers also write letters to inmates.

“The purpose of Books 2 Prisoners is to create humanity for a person who’s in this situation in their life,” said Jane Crosby, co-chair of B2P. “Because a lot of time, we’re the only mail they get.”

When the pandemic first hit, nothing was allowed into prisons from volunteer groups. As prisons begin accepting book donations again, they are quarantined for a certain period before giving them to inmates. B2P must also comply with other restrictions: no hardcovers, spiral bindings, or shiny paper, because these could theoretically be used as weapons.

“People have been writing us for years; we have a relationship,” said Crosby, and when you commit to volunteering, you don’t stop just because it’s not convenient.

Giving books to people in prison can create hope, develop skills and improve reading, writing and literacy, said Jeff Bradley, the group’s other co-chair. “The least we can do is communicate and create human connection, one-on-one with folks, and try to address some of their concerns or questions.”

B2P doesn’t deliver to the local Ottawa-Carleton Detention Centre (OCDC), but Bradley says the group is talking with the jail about protocols for getting books into that institution. In the meantime, the group delivers books to inmates at three Ontario prisons: Bath Institute, Warkworth Institute and Algoma Treatment and Remand Centre. B2P also donates self-help books to the resource library at Collins Bay Institution.

Poor conditions worsen

Souheil Benslimane is a different kind of volunteer. He’s the co-ordinator of the Jail Accountability and Information Line, which takes calls from prisoners inside OCDC, tracks their complaints and connects them with supports in the community.

During the pandemic, complaints have ranged from health care issues to decreased visits. In October, an outbreak of coronavirus occurred at OCDC.

“There are complaints around COVID protocol and how information is not given to prisoners; they’re kept in the dark most of the time,” said Benslimane.

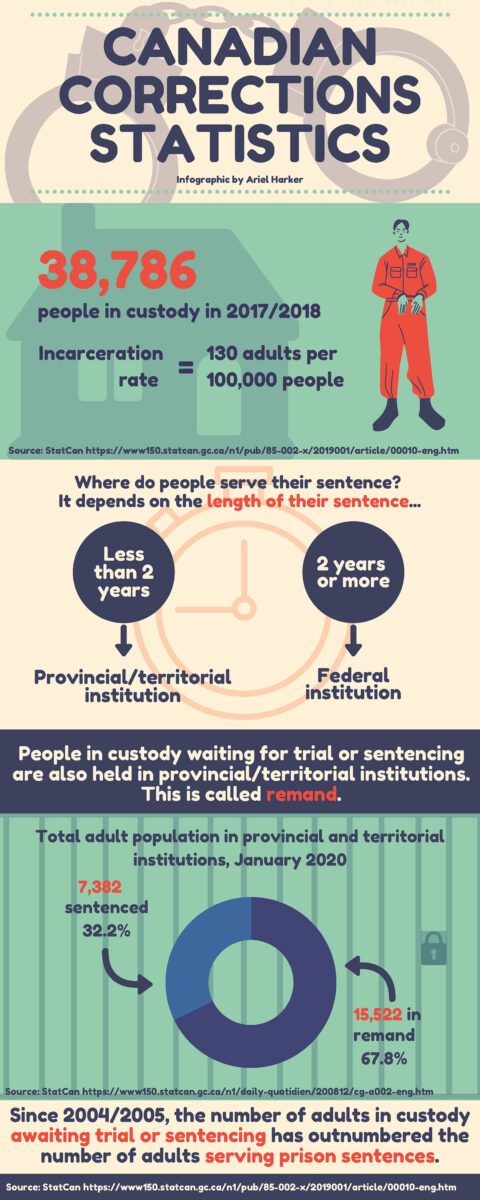

Earlier in the pandemic, the jail’s population decreased to 60 per cent of its normal 585-person capacity, Benslimane said, because judges were imposing conditional sentences, which are served outside of jails. And early or temporary releases were given to some offenders because of the risk of COVID-19 in jails.

“Those numbers started climbing back up when COVID became ‘normalized,’ in a sense,” he said.

Some diversion measures are continuing. Last month, for example, a judge reduced a man’s sentence for assault because of the quarantine and harsh conditions he experienced while at OCDC.

Even before the pandemic, the jail had almost no volunteer programming for inmates, said Benslimane.

Setting up volunteer programs for jails can be a challenge. For example, by the time books make it through the inspection process to get into a short-term detention centre, the inmate may already be gone, Crosby said.

Prisons that house people with long sentences are easier to deliver books to, she said.

“They have a better setup for distribution of books and people owning stuff,” said Crosby.

With COVID-19 precautions in place, some Canadian prisoners have reported being locked down for 22 hours a day, said Fallis.

“We’ve all had these kind of 14-day quarantines, and these guys are doing a lot more than that,” said Fallis. “And they’re doing it without Netflix too.”

Editor’s note: The article has been updated from the original to reflect the CSC’s Dec. 16 announcement.