Bats and bed bugs? Oh my! Insect infestations have been reported in several federal buildings this year, and one public sector union recently posted a video of a bat flying around inside an office. But Ottawa’s public servants also continue to share space with more conventional pests: mice.

“If you find droppings, it’s bad news because it means they’re getting close to us and going through our stuff,” said Olivier Caron, who works on the seventh floor of L’Esplanade Laurier, at the corner of O’Connor Street and Laurier Avenue, for Public Services and Procurement Canada.

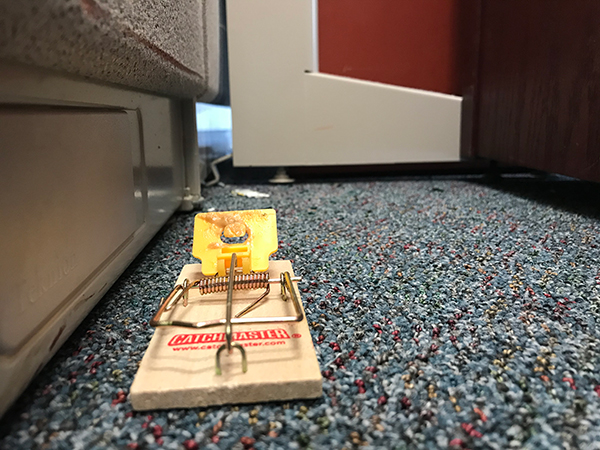

Caron found mouse droppings on his desk in August and decided to bring traps from home to catch the culprits. He caught one mouse in a co-worker’s office in September.

“It’s something that happens in pretty much any building,” said François Dicaire, co-chair of L’Esplanade Laurier’s health and safety committee. “Here the mice actually are quite bold, they come out during the day and run across the floor, so people do notice them.”

How widespread the problem is in federal buildings isn’t generally known. But health and pest experts say the age and condition of buildings such as L’Esplanade Laurier are likely to blame for the presence of mice. The Public Service Alliance of Canada wants action from the government to deal with all pests.

“Finding droppings is always a bad sign because you can get disease and viruses from them that can actually kill you,” Caron said. According to the Canadian Centre for Occupational Health, mouse droppings can spread diseases such as Hantavirus, and others that can be fatal.

Capital Current contacted PSPC for information about any steps the government is taking to address the presence of mice in federal buildings. In an emailed statement, PSPC spokesperson Marc-André Charbonneau said, “We understand that employees are concerned about the presence of mice in the workplace and we take these concerns very seriously.” PSPC, he wrote, is “committed to maintaining a pest free workplace for its building occupants.”

The email did not identify which government buildings are dealing with mice, but said, “Some buildings are more susceptible to pest infiltration than others.”

PSAC said it has not received any information from the government about mice at L’Esplanade or what it is doing to address the potential wider issue. Last month, union representative Kyle MacDonald said the union was unaware of a specific mice problem in L’Esplanade.

But workers in the building are certainly aware of it.

In 2015, employees at L’Esplanade made the near-vacant building their home because reconstruction was being done at their original office at Place du Portage in Gatineau.

Before employees from PSPC and the Department of Finance moved into L’Esplanade, which will be their temporary home until 2025, a retrofit was performed to ensure the 46-year-old space was habitable. At the time, a mice infestation was found.

“There were quite a few horror stories about people (who have moved out) leaving food in the fridge unplugged … on those floors there were quite a few mice so they actually had to condemn those floors, to seal them off and actually fumigate,” said Dicaire of the retrofit work.

Since then, Dicaire said, the infestation has been better controlled and no health issues have been reported in relation to mice. He wonders, though: “Will we ever completely eradicate the problem? That’s still to be seen, we try to control the problem as much as we can.”

Alex Silas, PSAC’s alternate regional executive vice-president for the national capital region, said that “any mice, even just a single mouse in a workplace, is an issue for us. I mean it’s not cute, right; any mouse is a severe health and safety issue for our members.”

PSAC is seeking further action from the government for all pests.

“We’re asking for pro-active inspections for mice, for bed bugs, for all sorts of pests,” said Silas, “Members should be given the option to telework, they should be given accommodation so they don’t have to work in an environment that might carry disease or just have pests in general.”

Silas also said the union is “looking for a registry to keep track of these buildings and for transparency from the government so that they can tell us what steps they’re taking and where pests have been found. And they should cover all expenses for fumigation and treatment.”

Meanwhile, Dicaire said the health and safety committee’s main focus is to educate people. “We try to tell employees to not leave any food lying around … We’ve also replaced the garbage cans in the kitchen areas so that all of them have lids, and any garbage is not left in the open because that definitely will attract [mice].”

The government statement echoed this focus. While spelling out how the department works with pest control experts, it noted: “Pest management is a shared responsibility with departments and cooperation is required from building occupants to ensure workspaces are wiped clean, food is stored in sealed containers, and kitchens remain tidy.”

According to Dicaire, “building property management has deployed as many traps as they could where the problems were known … they’ve also tried to spot and plug all the possible entry points throughout the exterior of the building.” This has helped, he said. “However, there are mice in the building, and they do pro-create and make little mice.”

‘Ottawa is the capital city of mice’

Auday Edan, owner of Pest Patrol Ottawa, says older buildings are easier for mice to get into because of more holes and cracks in the structure’s foundation. Edan refers to Ottawa as “the capital city of mice.”

“Mice are everywhere and their activity is increasing because nature is very rich in this area,” in part because governments don’t use pesticides to remove weeds from lawns, and people seed them generously instead, said Edan, who has been in the pest removal business for over 15 years. That’s an attraction for mice.

Edan says another major contributor to Ottawa’s pest problem is the amount of feeding that goes on in the city.

“People have bird feeders, but at night they become mouse feeders. They feed the birds outside, but throwing seeds and left-over lunches to pigeons will attract mice and rats.”

As well, mice respond to the city’s more severe weather conditions such as heat, or snow.

“In October, November and December they’re more active, and after that it’ll calm down, and then pick up again in June, July and August,” said Edan.

Since mice are social and territorial, Edan says they tend to flock to structures to find shelter between walls. By leaving food around, workers are asking for an infestation.

What qualifies as an infestation? “Some people will refuse to live in a house with one mouse in it, others don’t mind if there’s 100 mice living with them,” he noted. “Seeing a mouse in a mechanical shop or a school is much different than seeing it in a hospital or at a Tim Hortons.”

The L’Esplanade building houses three restaurants: Tosca Ristorante, Thali and Bytown Bayou Louisiana Smokehouse. Employees at those restaurants say they have not seen mice in or around their establishments.

Edan says the best method of dealing with mice is prevention.

“If you catch the mouse inside then it’s too late, you have to catch them before they get in, or else they’re going to keep coming.”

Bait stations, for instance, can prevent the critters getting inside.

“They’re basically these heavy, black boxes with tiny holes on their sides where mice go to feed on pesticides. They usually die in 24 to 48 hours after consumption,” said Edan. The poison inside a single bait station can kill up to 7,200 mice.

As for how long it would take L’Esplanade to remove rodents, Edan believes it could take a few months considering that for an average-sized house it takes about three weeks. “It depends on how many bait stations we use, and how many holes we need to block; they could be looking at a $2,000 or $3,000 removal,” said Edan.

Edan’s advice to the workers at L’Esplanade and other buildings is to keep the building clean from the inside out, to provide the mice with as few food sources as possible, and to keep all garbage together, where it belongs. He says the rest is up to the management of the building.

In such a large complex it’s difficult to address pest issues without employees submitting a formal report, Dicaire says. “It creates a ticket which is then sent to the building property management here at L’Esplanade. They in turn dispatch an employee to investigate and if it’s a recurring problem, an extermination company will come in and install traps.”

Submitting a report will also allow management to track if the mice are coming from a specific origin point or if they’re spread out across the two towers in L’Esplanade.

So far for 2019, Dicaire said that only “six or seven” official reports of mice have been submitted to the Health and Safety committee.

Despite potential health worries, Caron, the employee who laid mouse traps in the summer, says he’s not overly concerned. “There’s always a mouse population somewhere, there’s always food and water in big buildings like ours,” he said. Putting in traps and poison is “never going to get rid of 100 per cent of the critters.”

Silas says that to him, a controlled pest problem wouldn’t mean merely keeping the mice population at the workplace manageable. “Control should be making sure that there are no pests, mice, rodents, otherwise, in the workplace at all.”

He says if the government’s standard for a controlled pest problem is “mice running across your desk and leaving droppings, bats flying around, and bed bugs being found … well, then, they clearly need to raise their standard.”

Union representing federal employees (PSAC) is sharing this video of a bat that was filmed inside the Terrasses de la Chaudiere gov’t building. PSAC says it highlights ongoing concerns about health/safety of employees there.@ctvottawa pic.twitter.com/x3ZEllyj3A

— Megan Shaw (@meganshawCTV) October 29, 2019