In the darkened bedroom of a trailer a woman silently slides out of bed.

She looks over her shoulder at her sleeping partner, carefully ensuring she does not make a sound while slipping on her shoes. Almost holding her breath, she tiptoes into her daughter’s room, shushing and lifting her out of bed as she moves down the hallway.

The camera pans down to show the glass-strewn floor and a gaping hole in the wall of the kitchen. The two make it out the door and into the car as the woman drives off as fast as she can — leaving her awakened and perturbed partner yelling on the doorstep in the distance.

Although this is the opening scene in Netflix’s latest limited series, Maid, it is also a situation with which some women are all too familiar.

Based on a true story and book by American author Stephanie Land, the series follows 23-year-old Alex (played by Margaret Qualley) and her escape from her abusive partner Sean (Nick Robinson). The show narrates challenge after challenge — including poverty, homelessness, family conflict, custody hearings, mental health struggles and a dead-end minimum wage job — facing the young single mom.

Following the series release on Oct. 1, experts on intimate partner violence noted the accuracy of the series — something they say has been lacking in television and film for far too long.

Too often, TV shows, movies and news media fail to depict the complexities and “contexts” of domestic violence, said Naji Naeemzadah, PhD candidate at Western University in London, Ont. As part of his research, he focuses on exploring media portrayals of intimate partner violence and its implications for policymaking at the federal level.

He said in general, news media and various on-screen depictions of domestic violence are similar.

“They all come to the same conclusion. Intimate partner violence, or gender-based violence, more broadly, is not portrayed in a way that provides context. And context is very important … in understanding the causes and the consequences and the nuances of abuse,” said Naeemzadah.

“(Maid) and shows like that, I think are very helpful in terms of providing that context that really captures the nuances, the impact and the consequences of violence that is experienced. … And we don’t really see that in other media platforms.”

Naeemzadah noted that in some cases the story and experience of domestic violence is condensed, as there is not always the “space and time” for providing what he refers to as full “background information”.

“(Other media) usually focus on the end (result)… But then (in) shows like Maid, the intention really is to highlight and capture the experience of intimate partner violence,” said Naeemzadah.

He said this is important, particularly since the reality of what intimate partner violence entails can be misrepresented.

This is one of the major points of contention for Alex’s character in the show.

Coming to terms with the fact that she has been emotionally abused, she initially wants to refuse a bed at a domestic violence shelter. For Alex, she assumed she was not abused because her partner “never hit her.”

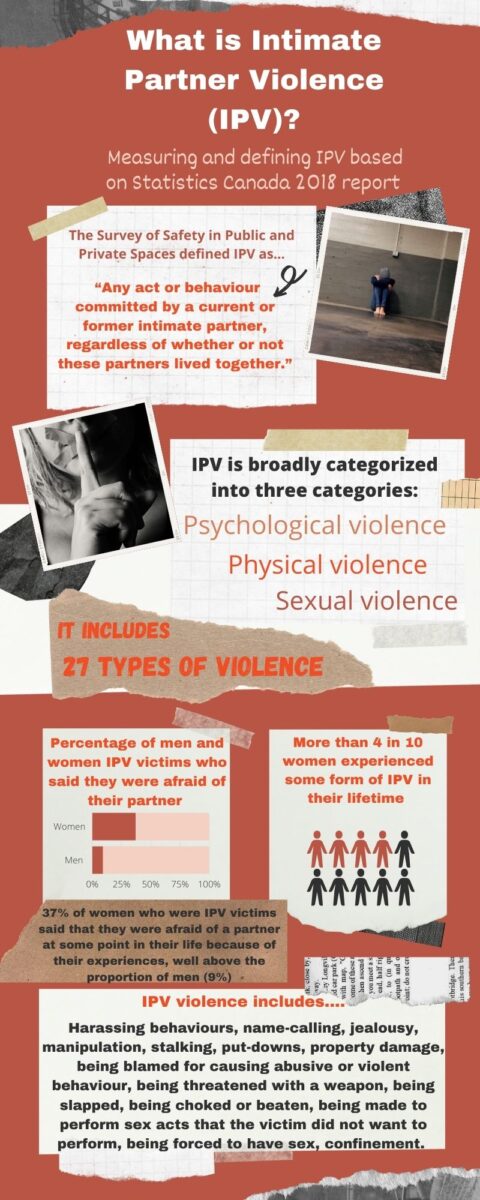

According to a 2018 Statistics Canada report on intimate partner violence in Canada, intimate partner violence is much more than physical abuse. It includes 27 types of violence and psychological, physical and sexual violence.

The violence can range from put-downs, manipulation and name-calling to being blamed for causing violent behaviour, or being slapped or choked, said the report.

According to the Statistics Canada data, at least four in 10 women experienced some form of intimate partner violence in their lifetime, with psychological abuse being most common. Additionally, the report found that almost 43 per cent of women have experienced some form of emotional, financial or psychological violence since age 15.

“When people hear the word violence, they usually think of physical or sexual assault, but you know there’s much more tangible parts of violence… emotional assault, emotional abuse, there’s financial abuse,” said Naeemzadah. “It is a major problem at the moment…because (these kinds of) reports don’t get published…We rarely read about the mental or the emotional or financial abuse that’s quite prevalent in intimate partner violence.”

In this sense, Maid is unusual in a good way, said Jordan Fairbairn, associate professor in the Department of Sociology at King’s University College at Western University. She noted that by depicting what she calls the “power and control processes” in domestic violence situations, the show pushes back against these problematic tropes.

“A lot of popular culture and media representation of domestic violence have really emphasized physical violence in a very sort of exaggerated or simplistic way,” said Fairbairn. “From what I saw… I thought (Maid) really captured just how isolated she was and how big of a role isolation plays in terms of the tactics that abusers use.”

A big part of the show surrounds these tactics and the cyclical nature of domestic violence — how Alex’s relationship with Sean gets complicated by their history, the fact that they have a child together and how, without him, she is completely isolated.

Fairbairn said by depicting these secondary factors, the show addresses one of the common questions people who have never been in situations of abuse tend to ask: “Why doesn’t she just leave?”

“We often see this trope that . . . there's a whole host of supports out there, if only the person would choose to leave,” said Fairbairn. “And so what we see in these episodes is that she's very much trying to access support, but the bureaucratic mechanisms and policies are sort of pushing her down and forcing her back into abusive situations or dangerous situations or situations of lack of housing at every turn.”

What we do not often see in terms of popular representations and news coverage are these economic realities, said Fairbairn — the factors that make it difficult for abused partners to leave permanently.

“This idea that people often have in thinking that well, ‘If that happened to me, I would just leave, I would never let someone treat me like that.' I think (this show) sort of brings some nuance to the complication," said Fairbairn. "I thought that it was helpful to an audience to see that."

Although the movie differs slightly from Land’s original story and experience, she noted in a recent interview with the Book Report Network how the show's adaptation did a great job of introducing new elements while maintaining her original storyline.

“(Everybody) wanted to make a movie that was a pure adaptation of the book . . . but that’s just not what I wanted. I wanted diversity, and to be able to expand on my story,” said Land. “They did a fantastic job, they made the series look like the real world looks.”

Fairbairn noted that while these types of shows — depicting "real world" abuse and secondary complications to domestic violence — by no means act as a driving force or inspiration for women in abusive relationships to leave, they do have the ability to positively affect people in positions of power and privilege. She said it can allow for some to potentially reflect on the ways in which they could help people in similar situations in the future.

“If we watch the show… (questioning) ‘what could I have done, as that social worker, or as that homeowner whose house she was cleaning or, you know, as that parent or family member or bystander . . . then I think that is potentially helpful," said Fairbairn. "If the next time that we have some sort of opportunity, whether that's through our work or research or relationships or our workplaces, if we have some opportunity to support or to intervene in the situation or offer resources . . . maybe that would be helpful"

She added: “For those who have more power and privilege in society to watch something like this, (questioning) am I part of the problem here? Like in what ways can I be part of the solution? I think that could be promising.”