New nuclear waste guidelines set to undergo public consultation this fall could clear the way for a much-debated, large, above-ground waste disposal mound to be built at Chalk River, the national nuclear research facility 180 kilometres northwest of Ottawa.

The proposed guidelines would frame the way nuclear companies dispose of waste, including the creation of deep ground repositories. Under the guidelines, companies would present waste disposal safety cases — a set of justifications for a planned disposal strategy — which are then assessed by the Canada Nuclear Safety Commission.

But one longtime critic of the Chalk River site says the guidelines would give too much flexibility to operators of nuclear facilities. Ole Hendrickson, a former scientist with Environment Canada and a researcher with the Concerned Citizens of Renfrew County Area, says the guidelines need to be more stringent.

“In my view, what they say is, ‘Let’s make these reg docs as flexible as possible and non-prescriptive’ — and the CNSC actually uses those terms, non-prescriptive and flexible, to describe its regulatory approach,” he said. “That may work for industry, but for us members of the public, it raises a lot of concerns.”

In the minutes of a CNSC meeting on June 18, Ramzi Jammal, executive vice-president of the commission, said the safety cases allow for performance-based assessment and for the regulatory documents to be adaptable to future conditions.

“With performance-based you’re always achieving and applying the new standards as they become available. The same thing applies for the new technology,” Jammal said at the meeting. “As you are looking at enhancement for safety, you always take into consideration the new available information.”

Chalk River

A proposed above ground waste repository at Chalk River would contain low-level waste, typically equipment used in reactor operations or from medical, academic or commercial uses of radioactive materials.

But what is defined as low-level waste is flexible and depends on the safety cases presented to the CNSC, said Richard Cannings, NDP MP for South Okanagan-West Kootenay and the party’s natural resources critic.

“That’s a problem. That’s not how it’s done elsewhere in the world,” he said. “They did it in Ottawa’s backyard.”

In the June 18 meeting, Karine Glenn, director of the wastes and decommissioning division for the CNSC, said low-level waste would mostly involve medical materials, but each safety case would be reviewed by the CNSC.

In Chalk River’s case, critics such as Eva Schacherl, a volunteer with the Coalition Against Nuclear Dumps on the Ottawa River, say they believe the “massive waste dump” would fail to manage the nuclear waste safely and that operators are failing to meet international standards at the site.

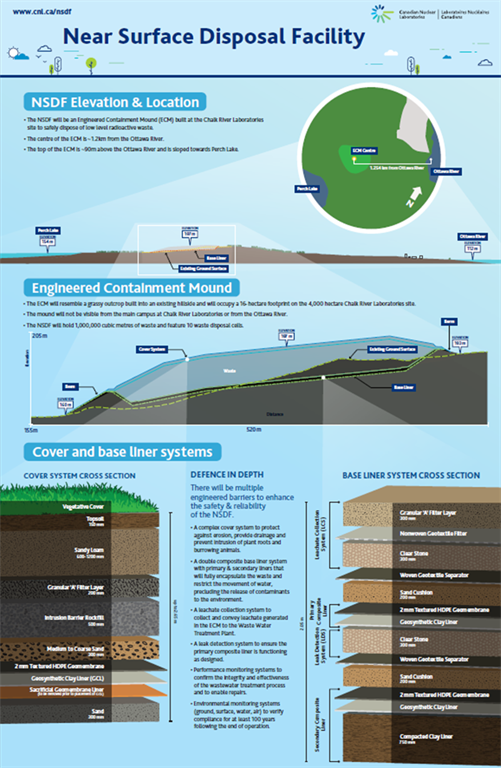

[Infographic courtesy of Canadian Nuclear Laboratories]

“Canada should be setting an example of the highest standards and the best approaches to managing nuclear waste,” said Schacherl.

The best approach to managing nuclear waste is ensuring the safety cases are up to standard, Haidy Tadros, director general of the CNSC, said during the June 18 meeting.

“We have focused all of our efforts, whether they be documenting and aligning with international standards or national standards, on the focus of the safety case,” said Tadros.

But both Schacherl and Hendrickson said they are concerned the site — which is within a little more than a kilometre of the Ottawa River, according to Hendrickson — could spread contamination.

“Waste has piled up at Chalk River, and there’s no long-term way of dealing with it,” said Hendrickson. “There would be a lot of leaching that would flow back into the Ottawa River.”

According to the Canadian Nuclear Laboratories website, the design would include layers of dirt and “engineered protection” over the waste to prevent it from being exposed to rain and snow, guarding against contaminants leaching away. The proposal also features a water treatment plant.

Deep ground repositories

Hendrickson said finding a long-term solution to Canada’s nuclear waste is key, as many nuclear reactors and sites are coming to the end of their commissioned life. For example, Pickering’s nuclear facility will stop commercial operations in 2024, and start decommissioning in 2028.

Chalk River’s nuclear reactor was shut down permanently in 2018, but the facility continues to carry out a wide range of research related to nuclear energy.

Radioactive waste is also generated while decommissioning and dismantling nuclear reactors and other nuclear facilities. High-level waste, like spent fuel rods, are the most radioactive and, as of yet, Canada has nowhere to put them, said Cannings.

“There’s the concern about an accident happening, but the big concern is what do we do with all the nuclear waste that’s left over?” he said. “We still haven’t come up with deep repository sites that will deal with this.”

The Nuclear Waste Management Organization — funded by Ontario Power Generation, NB Power, Hydro-Québec, and Atomic Energy of Canada Limited (which owns the Chalk River facility) — is the agency responsible for the design and construction of Canada’s first deep ground repository.

“In my view, what they say is, ‘Let’s make these reg docs as flexible as possible and non-prescriptive… That may work for industry, but for us members of the public, it raises a lot of concerns.”

Ole Hendrickson, Former scientist with Environment Canada and researcher with the Concerned Citizens of Renfrew County Area.

Hendrickson said the NWMO shouldn’t be responsible for constructing nuclear waste disposal sites when they are funded by large producers of nuclear waste.

“Most countries with large quantities of nuclear waste have an independent federal nuclear waste agency,” said Hendrickson. “It’s not run by the industry like the Nuclear Waste Management Organization. It’s definitely not run by the nuclear regulator.”

Cannings agreed, adding that he was worried what impact having the NWMO responsible for the deep ground repositories could have for safety.

“There’s risks with everything. But the assessment of risks to a project by the proponent, by the industry — they’re going to be much more favourable, they’re going to accept more risk than the public because they’re protecting themselves,” said Cannings.

Two Ontario sites — South Bruce, near London, and Ignace, a three-hour drive northwest of Thunder Bay, are the only two communities still vying for the deep-ground repository project. Both proposals have been met with resistance from local residents.

The NWMO declined to comment on the regulation documents and the proposed sites, as they are still being reviewed.

“NWMO is responsible for the safe, long-term management of used nuclear fuel, in a manner that protects both people and the environment. As an organization, we’re committed to meeting and exceeding all regulatory requirements,” said spokesperson Bradley Hammond in an email.

During the June 18 meeting, Glenn said the NWMO’s decision for the deep ground repository site would be evaluated using the safety case method, and that in instances where nuclear waste would need to be transported a long distance to the deep ground repository, another alternative may be best.

The CNSC also declined to comment on the regulations.

Public feedback

If the CNSC approves the final versions of the proposed regulations, a further round of public consultations will be held.

The consultation, likely to happen this fall, will be key, according to Hendrickson.

“It needs to be a national discussion, and not just something that happens where the nuclear industry is dictating the policy to us, which has been the case in the past,” said Hendrickson.

Critics noted that several organizations and advocacy groups had requested but were denied permission to be present at the June meeting where the regulatory documents were presented via video conference.

“In accordance with well-established processes for Regulatory Documents development, the CNSC Staff indicate that they have reached the stage to propose these drafts after undertaking all of the rigorous steps in the consultative process, including seeking public input,” CNSC president Rumina Velshi said at the meeting.

A public consultation period of up to 120 days were held for each of the regulation documents. The CNSC also held public workshops to get additional feedback.

“There’s risks with everything. But the assessment of risks to a project by the proponent, by the industry — they’re going to be much more favourable, they’re going to accept more risk than the public because they’re protecting themselves.”

Richard Cannings, MP for South Okanagan-West Kootenay, and NDP Natural Resources Critic.

This shows the CNSC’s commitment to involving the public, said Brian Torrie, director general in the CNSC’s regulatory framework directorate.

“The fact that we take this to a public meeting and discuss it, that is not the normal procedure across other federal regulators, partly because they don’t have a tribunal like we have. But I think it speaks to the depth and amount of consultation we do in these documents,” Torrie stated in the meeting.

During her presentation, Velshi added that international reviewers said the final version of the regulation documents should be in line with the International Atomic Energy Agency safety standards.

But critics such as Cannings remain unconvinced.

“There’s no reason why Canada — one of the leading countries of the world in terms of wealth and innovation and ingenuity — why we have to accept second-rate regulations when it comes to nuclear safety.”

[…] CANADA. Problems in planned nuclear waste dump at Chalk River. […]