Gordo the 90-foot-long Barosaurus. The Egyptian Book of the Dead. A meteorite from Mars. The Striding Lion of Babylon.

Those are just some of the wonders from the past that drew more than 1.3 million people to the Royal Ontario Museum last year. Now, its imposing front doors are closed, its famous dinosaur gallery stands silently in the gloom, as Toronto hunkers down for its second lockdown.

As the pandemic drags on, museum-lovers across the country are holding their breath: how many of our museums will survive the shutdowns, the plummeting attendance, the lingering fear of gathering in public spaces? And what will the ones that do survive look like, in a post-pandemic world?

“COVID has been a bit of a disaster, frankly, for everybody,” David Dean, a public historian and Carleton University professor, said. “But for museums, I think we’ll find that the world has much fewer museums than pre-COVID, for sure.”

Almost 13 per cent of museums around the world are expected to close permanently – including 10 per cent in North America — a May 2020 survey by the International Council of Museums (ICOM) found. An additional 20 per cent of North American museums were “not sure” if they would close, meaning that Canada and U.S. could lose up to 30 per cent of their museums because of the impact of the pandemic, the report said.

If museums go under as a result of the pandemic, it would deal a blow not only to Canadian history and culture, but also to the economy, research suggests.

The Canadian GLAM sector (galleries, libraries, archives, museums) contributed $11.7 billion a year in gross value to the Canadian economy, according to a 2019 Oxford Economics report. Additionally, for every $1 invested in non-profit GLAMs, society got nearly $4 back, the report found. The sector also accounted for more than 37,200 jobs in 2017, and it generated more than $2.6 billion in revenue in 2017, according to a 2019 Canadian Heritage report.

The federal government has stepped in to help museums through the COVID-19 crisis, adding a $53-million pandemic emergency fund to its Museums Assistance Program at the beginning of the crisis. However, representatives for the sector say the nation’s museums will need more government money to withstand the toll of the pandemic.

“We are very appreciative of the short-term emergency funding that was provided by the federal government to museums,” said Rebecca MacKenzie, a spokesperson from the Canadian Museums Association. “We are, however, extremely concerned about longer-term survival.”

The CMA, which represents more than 2,000 museums across the country, has asked for further emergency support in its 2021 budget proposal, as well as permanent funding of $60 million a year from the federal Museums Assistance Program, a large step up from the $16.2 million it received in 2016-17.

Planning for a post-pandemic world

Museums are not only fighting for their lives in the immediate term; they are also scrambling to adapt to the post-pandemic world. Public fear of contagion is widely expected to persist long past the pandemic — a trend that has many museums rushing to ditch the high-touch, interactive displays they have embraced in recent years, in favour of touchless alternatives.

Christine Conciatori, the director of planning and learning at the Canadian Museum of History in Gatineau, laughed as she explained how the pandemic has dramatically changed the nature of her job.

“I mean, my job is planning, and I made a joke to colleagues that my title should be changed from director of planning to director of improv,” Conciatori said by videoconference from her home office.

While museums started in the 19th century as simple displays of artifacts beside plaques explaining their significance, they have been reinvented since. Much of the museum experience today relies on interactive and immersive experiences, especially when it comes to children, a chaotic demographic for whom Conciatori is trying to plan safe exhibits.

“Do we go through any activities where they jump and they do things with their feet so they don’t have to touch? Let’s face it, the three-year-old will put his or her hand on the floor. That’s the nature of a kid,” she said.

Conciatori foresees a major change in social attitudes when visitors enter the museum and experience the exhibits after the pandemic has passed, especially among children.

“They’re little sponges, and they’ve been taught for seven months now. ‘Wash your hands all the time. Don’t stay too close. Don’t touch this. Don’t do that,’ ” Conciatori said. This will have a lasting impact on future museum visitors, she said: “Little kids will grow up into older kids and not want to touch other people or other things.”

Young people make up a large proportion of museum visitors: more than a million elementary and high-school students visit museums in Ontario every year, according to a 2016 estimate by the Ontario Museum Association. That means at least half the total student population of the province visits a museum in the province every year, the OMA said.

Maureen Fitzhenry, spokesperson for the Canadian Museum of Human Rights in Winnipeg, said the museum has been preparing for the post-COVID audience.

Look but should we touch?

“Even if the coronavirus has gone, people may still be wary about touching things, and that might last for forever. Who knows?” Fitzhenry said.

The CMHR has been offering online tours of its exhibits or catalogues for those who miss experiencing a day at the museum. By selecting the “explore from home” option on its website, virtual guests can access videos of museum staff giving personal tours to the camera. One such video of a peppy tour guide showing off various exhibits has had over 20,000 views at the time of writing.

“We wanted to do that anyways, because not everyone can visit the museum in person. … Even if there wasn’t COVID, we really want to have a robust and rich experience on the Internet,” Fitzhenry said.

The CMHR is far from alone in this endeavor. The Royal Ontario Museum, Royal British Columbia Museum, and the Canadian Museum of History have all adapted some activities and exhibits for the virtual space.

But the online experience isn’t for everyone.

Online exhibits don’t come close to the experience of visiting the museum in person, said Eric Huang, a member of the Young Patrons Circle for the ROM, a networking circle of young professionals who love museums.

Virtual reality

“The experience is not really similar from going to the museum and doing a virtual tour online,” Huang said. “The feeling that you get from going to a museum — all the history, the smell of it, being able to see people — (is) very different from watching a documentary in your home, right?”

In anticipation of the day when visitors can resume in-person trips, museums are also experimenting with new technologies such as virtual reality to offer their guests a touch-free experience.

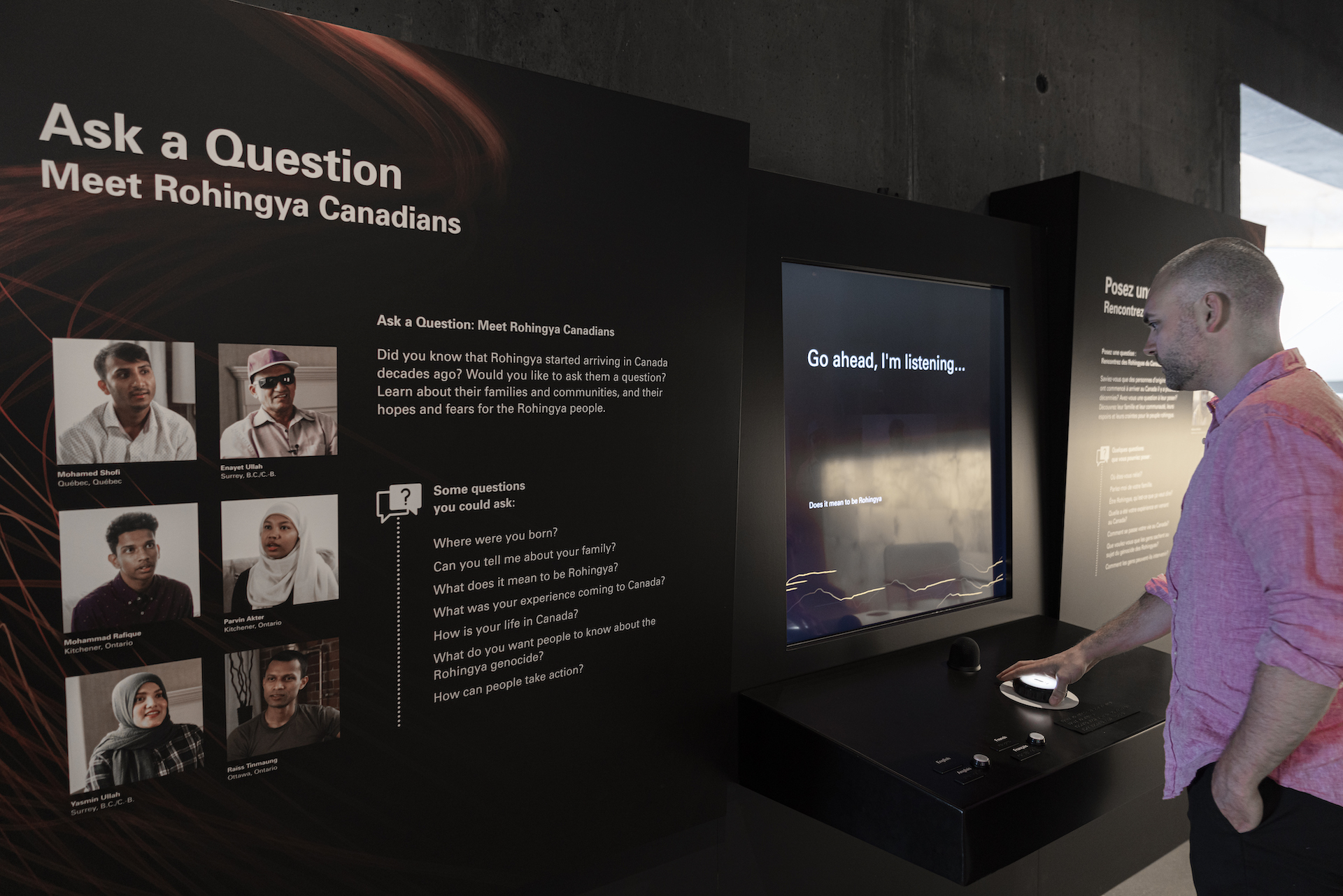

For example, the CMHR is trying out voice-activated exhibits that work in much the same way as the popular voice assistants, Siri and Alexa. Fitzhenry explained that the CMHR was already using this tech before the pandemic struck, in an exhibit about the Rohingya, the minority Muslim group targeted in a brutal 2017 crackdown by government forces in Myanmar.

When visitors approach the exhibit and ask a question, a video of one of 12 different Rohingya people appears on the screen to answer, she said.

The exhibit was closed when the pandemic was declared because visitors still had to choose a language on a touch screen, but this has only inspired further experimentation: the museum is now planning an exhibit that would be entirely voice-activated, Fitzhenry said.

Museums are also looking towards using virtual- and augmented-reality devices that will deliver their visitors straight into the exhibits themselves.

Virtual reality (VR) is typically delivered through headsets, such as the HTC Vive or Oculus Rift, which show a programmed and graphically rendered world with which the user interacts, moving freely through this virtual world, despite the confines of the room they are in. Augmented reality (AR) uses these headsets or just a phone camera to digitally impose created content into a real-world room. Whereas VR could place you on the site of a historical battle, AR may place the general in your living-room.

Dean said he got to try out an AR experience at a museum event in Finland last year and was blown away.

“They had an amazing AR experience where you basically, instead of touching everything in the replica building, you were just in a room, and you move through it, and you could touch things, and it felt like you were moving, it was just amazing,” Dean said.

At Carleton, Dean teaches his history students about the evolution of museums, from their inception as “cabinets of curiosity” to today. Now, he is living in the evolution.

“Five years ago, I would have been talking about (museums) letting people touch objects, letting people write their opinion on a sticky note, right? Now I’m talking about (touchless augmented reality), so who knows where we’re going to be in five years?” Dean said.

Fitzhenry said a move towards VR would be convenient for sanitation, as the headset is “a lot easier to sanitize than 100 touch screens,” and the CMHR has been looking into it.

Touch-free

But Huang said that, even after the pandemic is over, he would still hesitate to go to a museum that uses AR and VR extensively.

“I feel like I would do (AR and VR) less, because with AR and VR you would have to touch (headsets),” Huang said. “I would go to a museum to read stuff and watch stuff; I wouldn’t necessarily touch things post-pandemic.”

Touch-free exhibits that are triggered by gestures could solve that problem. Conciatori said the museum has used the motion control functionality from an Xbox 360 Kinect camera. Visitors could interact with exhibits by simply moving their hands in the air, to play a game, or press a virtual button, or anything else visitors would normally touch on a screen. However, she said that integrating technology into new exhibits, which take years to plan and build, can be unsustainable financially.

“Because technology evolves so quickly, something that was developed years ago, and is interactive, will quickly become obsolete,” Conciatori said. “When we develop something interactive, we always look at sustainability … because it’s expensive.”

Then there is the issue of how to include people with different abilities when introducing new technologies, said Fitzhenry.

“We are very conscious of the need for inclusive design: accessibility for people of all abilities. Touch is required, in some cases, especially for those people who are blind and (have) low vision,” Fitzhenry said. “We specifically have tactile things for them. So we need to be making (their) case, or putting forward things (for them) into the future.”

The issue of inclusivity extends beyond the logistics of making exhibits more accessible, some experts say. As museums reinvent themselves for a post-pandemic world, they should also seize the opportunity to re-examine more fundamental issues, such as how to become more inclusive in their content and their outreach, Dean said.

“The sorts of people that don’t come to museums are often marginalized, socially or economically, particularly economically,” he explained. This problem will only get worse, as the toll of the pandemic falls more heavily on these marginalized groups, he said.

“Parking is $10 at a museum. Not everybody can afford $10. So, you know that means you’re not attracting everyone in the community.”

Challenges and opportunities

The CMA is already making plans to address the challenges and opportunities the future presents. In a Dec. 16 brief to the Commons standing committee on Canadian Heritage, the association urged the government not only to raise its permanent funding allocation for museums, but also to fast-track a 2019 plan to update its vision for the sector that has stalled because of the pandemic.

Noting that federal policy is now 30 years old, the CMA argued it is “woefully out-of-date and simply doesn’t reflect a modern Canada,” adding that “an updated policy is vital to pandemic recovery and to establishing greater long-term resilience for the sector.”

The new vision promoted by the CMA would guide museums in integrating issues such as reconciliation with Indigenous peoples, climate change, and community-building, and set new policies aligned with those goals, as well as provide more funding for the digitization of collections and greater public engagement.

“A modern policy would increase alignment on the priorities, challenges and opportunities of these vital cultural institutions and help museums address key societal issues such as climate change, truth and reconciliation, and social cohesion,” the CMA’s Mackenzie explained.

Despite the challenges of revamping the design of exhibitions, concerns about accessibility, and the uphill battle for financial support, Conciatori said she remains optimistic that Canadians will find their way back to museums once the pandemic restrictions have been lifted.

“People will still crave going to see either beautiful artwork, or to learn, or to live and experience. And this cannot be replaced. I think people will crave it even more,” Conciatori said, “because once you’ve been deprived of something, that’s when you realize that how lucky you were to have access to all of this.”