For almost 60 years, Sharon Boddy, the director of Friends of Hampton Park and Carlington Woods, walked through the towering old-growth trees that filled Hampton Woods, a small urban forest in Ottawa.

The area is home to dozens of trees more than 100 years old (some more than 250 years old), including sugar maples that are struggling to survive in warmer temperatures than they are used to.

Boddy says that the changing climate is challenging old-growth forests, which are key to reducing atmospheric carbon. After hundreds of trees in Hampton Park were clear-cut and not replanted because of the increasing impact of invasive insects, now any new growth in the area might struggle to thrive.

“Some of our oldest trees in Hampton, such as our sugar maples, could be 200 years old,” Boddy said. “They’re already going to be dying, but the naturally regenerated ones may not be able to survive in our [rising] temperatures.”

As the third-largest forested country in the world, Canada is home to billions of trees. Once valued primarily as lumber and for the habitat they provide to myriad animal species, forests also have a significant role in fighting climate change, capturing and storing CO2 that would otherwise build up in the atmosphere and contribute to global warming.

These carbon capture benefits are best among old trees: According to a University of Hamburg study, nearly 70 per cent of all carbon stored in trees accumulates in the latter half of their lives. This means that Canada’s vast population of older trees is a deeply valuable tool in combatting climate change.

In the last four decades alone, Canada’s forests have sequestered around a quarter of the CO₂ produced by human activities. Still, these forests are under threat on various fronts.

Over the last decade, Canadian governments have announced various efforts to boost and conserve these vital forests, including the federal government’s 2021 commitment to plant two billion trees by 2031, and increasingly robust management plans for crown, provincial and urban municipal forests that incorporate current forestry science – the necessity of species diversity, for example – into reforestation.

Experts worry, however, that Canada’s tree-planting initiatives will not be effective in the long-term if the country doesn't counter warming temperatures and invasive species.

In 2022, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change announced that the world will emit enough carbon to exceed the global average temperature target of 1.5°C within the next 10 years. These rising temperatures can affect forest diversity and tree growth rates, making them less effective at storing carbon.

Tree populations are also susceptible to various threats that can challenge planting efforts. As highlighted in the Ontario Tree Seed Transfer Policy, the most obvious and prominent of these threats is the very crisis that these initiatives are meant to address: climate change.

Warmer, drier climates can make it harder for trees to thrive in their natural environments, presenting a clear challenge for new and existing forests, especially fledgling tree saplings.

“Last year in northern British Columbia, we had a few projects that we know we're going to have to replant just because it was so bone dry before and after the trees were planted — we really didn't get any rain on them,” said Randall Van Wagner, the head of Tree Canada’s National Greening Program. “It is creating difficulties.”

Tree Canada is one of the organizations the government has partnered with to fund and organize planting initiatives nationwide.

Van Wagner says climate change can present a range of hazards to new and existing forests, apart from altering growing conditions.

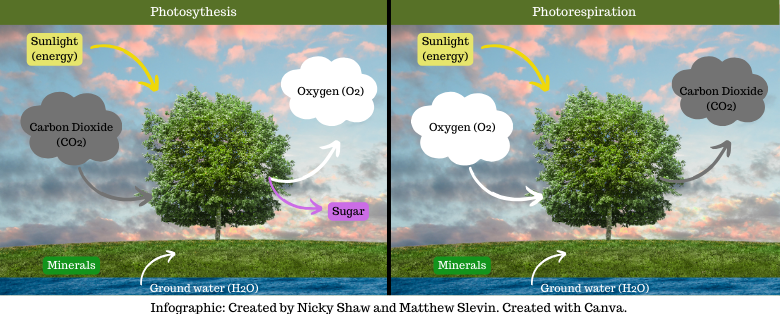

In fact, under stressful environmental conditions, some trees don’t absorb CO₂ through photosynthesis and release oxygen but instead do the exact opposite in a process called photorespiration. By studying wood samples from various global ecosystems, Max Lloyd, a Penn State geoscientist, found that the world’s trees can release up to two times more carbon in warmer climates than they’re used to.

Not only does this process add CO2 to the atmosphere, the trees cannot survive for any extended period if they aren’t getting the carbon they need to grow new leaves and branches, he said.

It’s a feedback cycle that leads to less CO2 removal, less ability for trees to grow and in doing so, absorb CO2.

He added that this is particularly concerning for northern or high-altitude environments, where temperatures are more variable and trees face a higher risk of releasing more carbon than they take in.

“Trees are very good at adapting, and they’re very good at acclimating to specific environments. However, it comes with limits,” said Lloyd. “Trees don’t have legs — they can’t up and move quickly to a new climate that is more amenable to them.”

Warmer temperatures can also create seasonal droughts, depriving trees and other vegetation of the water they need to grow. These dead and dry trees are also more likely to catch fire, which can lead to devastating wildfires.

While it can be challenging to quantify the exact effects of rising temperatures on plant growth and forest health, he said climate change has clearly increased the frequency and severity of forest fires. In addition to devastating communities, wildfires release sequestered carbon in a spiral that increases climate change, creating the conditions for more forest fires.

Canada had its worst-ever wildfire season in 2023, accounting for 23 per cent of the year’s total global wildfire carbon emissions, nearly five times the average from Canadian wildfire seasons over the previous two decades.

Invasive species like the Emerald Ash Borer have also exacerbated fires. The forest pest arrived in Ontario in the early 2000s and spread rapidly because of a lack of natural predators. It has killed millions of Ash trees.

Several bark beetles have had a similar effect on the West Coast. The mountain pine beetle outbreak that started in British Columbia in the early 1990s has affected more than 18 million hectares of forest.

“These insects can destroy a lot of forest, and they leave it with standing dead trees. A lot of that's basically fuel,” said Van Wagner. “Then you get these drought conditions that can lead to more intense and more powerful wildfires, which are harder to control.”

Since many of these pests target specific species, they tend to spread much more easily in forests that lack diversity. Dr. Sandy Smith, an entomologist and a professor of urban forestry at the University of Toronto, explained that this needs to be accounted for in forest planning.

“No one tree species should be more than probably two or three per cent [of a forest’s composition]. You don't know when the next invasive [species] is going to come,” she said.

Smith noted that, in addition to increased prioritization of tree populations, all levels of government have started taking these kinds of important measures to make populations sustainable over the last several decades. Governmental bodies like Ontario’s Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry (MNRF) are beginning to incorporate the findings of scientists like Smith into their efforts.

Still, she says, the government has only started taking forestry science seriously recently – this means that old-growth forests across Canada may still be at high risk of fire, droughts, and invasive species.

Because the federal government owns little forest land relative to provinces and territories, setting major targets for provinces and planting initiatives to follow, like the two-billion trees initiative, is the extent of its power for most forests in Canada.

Although the federal government says it is exceeding its own plans to meet this goal, some experts have raised doubts about their numbers. Smith acknowledged the good intentions behind the plan but remains skeptical of its narrow focus on hitting targets.

As we move forward, Ontario remains steadfastly dedicated to striking the right balance when managing our public forests. Our forest management policy reflects our ongoing commitment to sustainable practices, biodiversity conservation, and climate change mitigation strategies that will result in healthy and resilient forests now, and for generations to come.

Statement by Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry (MNRF)

“It’s good to have ambitions, but forestry people know it’s probably doomed to fail on some level,” she said. “It’s just kind of a numbers game. How are you going to count them? Will they still be there in 50 years or two years? They don’t just fall from the sky.”

The federal targets ultimately serve as guidelines for organizations and municipalities receiving federal and provincial funding for planting initiatives. Organizations like Tree Canada work toward these goals by arranging and funding these initiatives.

“We plant in pretty well every province, and I believe we have about 200,000 trees going in the ground this coming spring,” Van Wagner said.

The MNRF says it is working with Natural Resources Canada to additionally develop a provincial tree planting program within the federal two billion trees program that will issue calls to existing forest managers for proposals on planting incremental “trees over and above what is legally required to regenerate the forest after harvesting.”

Although Smith and Van Wagner agree there is nothing wrong with a lofty goal, the federal targets and funding programs have no specific requirements for species diversity, growing conditions or prolonged maintenance – conditions that would protect forests from warming climates, forest fires and invasive species.

As long as we're talking about the issues and as long as we're looking for the solutions, we've come a long way in forestry.

Sharon Boddy, the director of Friends of Hampton Park and Carlington Woods

Smith explained that more care should be taken at all levels in developing forestry to ensure that conservation and planting initiatives do more than just hit quotas. Still, the ambitious goal of two billion trees has no real downside.

“I always say it’s never wrong to plant a tree in the right place for the right reason,” she said.