As the pandemic surges into its second year, some are experiencing a side effect they were not expecting from the public health crisis: weakened vision.

A recent study in China found that, in the last year, near-sightedness in school-aged children was more common after isolating at home. According to the study, the prevalence appeared to be about three times higher in 2020 than in years prior for six year olds.

While children are more vulnerable to vision damage, Canadian optometrists are seeing the problem in patients of all ages.

Dr. Joelle Zagury, an Ottawa optometrist, said increased screen time and less time outside are two of the largest contributors to eye strain.

“Even pre-pandemic, a lot of people have computer-based jobs and plenty of student work is now digitally mediated,” said Zagury. “What that has created is this sort of ocular fatigue.”

Tear film, which protects our eyes from dust, dirt and bacteria, is being produced less because people are blinking less often while staring at screens, she added. Because of this, many are battling dry eyes and eye strain. While this is typically seen in older people, Zagury said she has seen it become more common in children and young adults.

Sam Bryant, a 22-year-old political science student at Wilfrid Laurier University, is one. After a recent trip to the optometrist, he said his prescription has changed dramatically. While he has worn glasses to combat his near-sightedness for several years, Bryant said he began having problems reading text on his computer screen in February.

“It was really hard for me to focus,” he said. “I started to notice that it wasn’t just when I tried to read a paper on my computer. It was labels that were close to me, they were a little bit blurred.”

Researchers call this and similar situations “computer vision syndrome.” While research into the phenomenon is limited to the Chinese study, Dr. Susan Leat from the University of Waterloo’s optometry and vision science program said increased online work during the pandemic may be the culprit.

“(The syndrome) includes eye strain, dry eyes, headaches and intermittent blurry vision after long times working with a computer, iPads, tablets, cell phones and other digital screens,” Leat said via email. “(But) computer vision syndrome does not lead to any long-term effects on the eyes or vision.”

While Bryant was wearing glasses pre-pandemic, people with perfect vision before COVID-19 struck have also seen a decline in their vision. Patricia Hammond, a 21-year-old education student at Memorial University of Newfoundland, said she has been facing computer vision syndrome since the middle of her fall 2020 semester.

“I’ve never needed glasses or contacts or anything, but in the fall … there were days where I would be on my laptop for 15 to 16 hours a day. I found that was very, very hard on my eyes.”

Patricia Hammond, an education student at Memorial University of Newfoundland

“I’ve never needed glasses or contacts or anything, but in the fall … there were days where I would be on my laptop for 15 to 16 hours a day,” said Hammond. “I found that was very, very hard on my eyes.”

Hammond seemed to exhibit symptoms of computer vision syndrome: blurred vision and headaches. She said she’s started using blue-light glasses to help mitigate her eye strain. While they have yet to be proven to protect eyes from the blue light emitted by computers and other screens, there are other ways to relieve straining.

Zagury recommended spending at least an hour outdoors each day to ease near-sightedness, as it encourages people to see farther than the four walls they’ve been surrounded by since the pandemic hit.

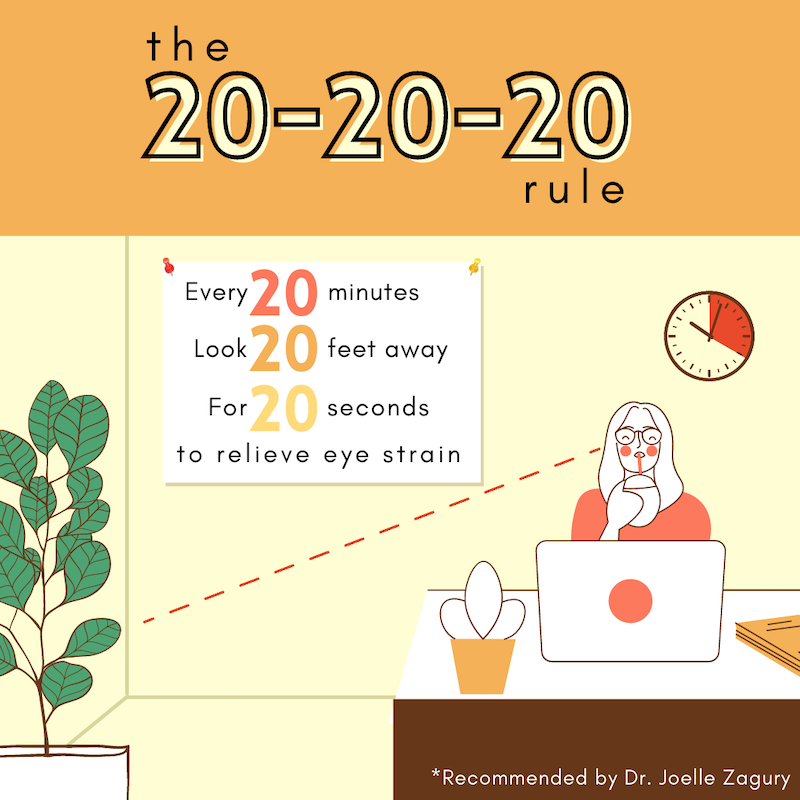

Frequent breaks are also helpful, she added. One suggestion in particular is the “20-20-20” rule, which recommends taking a 20 second break every 20 minutes that one spends looking at a screen by looking at something 20 feet away.

“If you’ve got a window, look out the window or take the opportunity to go to the washroom, maybe get a glass of water,” said Zagury. “You’re focusing into distance viewing, which is where your eyes are the most relaxed.”