Only a five-minute walk away from the town of Vathy in Samos lies the second most populated refugee camp in the Greek islands. What was once a military base built for 650 people, now shelters more than 4,200 men, women and children – with more arriving each day.

This summer, two Ottawa-based circus performers will call this crowded settlement home.

Kaylie Hatashita and John Shibley are co-founders of Rhopalo Circo Project. Shibley, 25, who is a tumbling and trampoline instructor at an Ottawa gymnastics gym, says the goal of their new organization is to “use circus as a tool for social change.”

By teaching youth in the camp to juggle and do handstands, he says he hopes to provide them with an opportunity to “express themselves creatively and … recapture the childhood that’s been stolen from them.”

Similar programs worldwide, led by groups such as Cirque du Soleil, are shown to be positive forms of therapy and a “way of healing” past trauma, says Hatashita, 28, a well-travelled performer who is now back home entertaining at local festivals and teaching at the Ottawa Circus School.

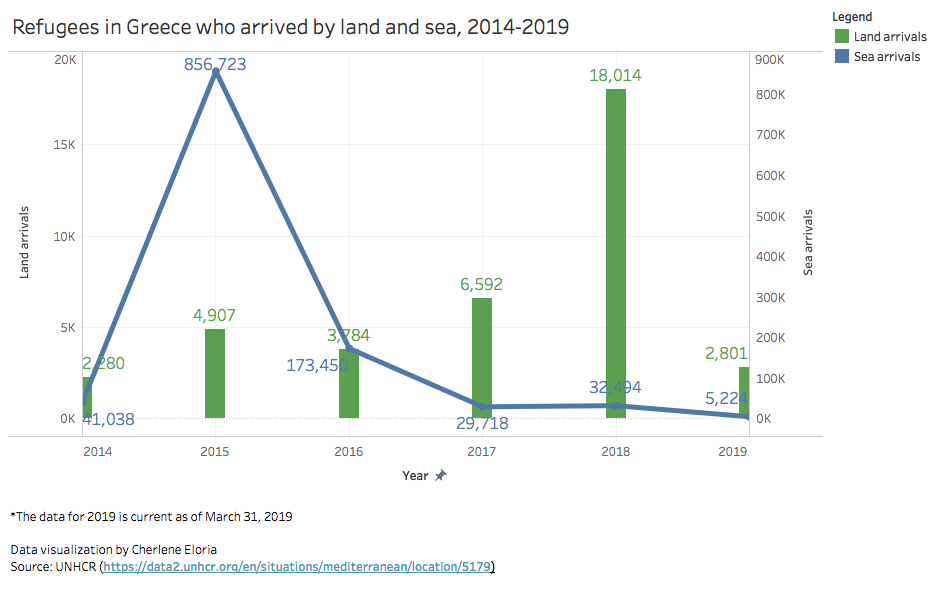

Shibley says they chose Greece for their first “tour” because it has taken a “huge percentage of influx in regards to the migrant crisis in Europe.” The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees estimates there are more than 74,000 refugees and migrants in the country.

With Montreal-based circus artist Pascal Duguay Gosselin and visual artist Millie Caron, the duo will run weekly workshops this May and June for the 1,000 children who live in the camp – 200 of whom are without parents or guardians.

Shibley says he hopes the kids will build confidence by seeing themselves progress in learning circus skills.

“If you’re paralyzed through a trauma that you’ve gone through, you lose the ability to explore and to learn,” he adds.

“I really hope to reinstill within these kids that curiosity for life and that joy of existence so that they can learn for themselves again.”

Rhopalo Circo Project is partnering with Samos Volunteers, the first of three non-governmental organizations who operate on the island.

According to communications co-ordinator Agustina Oliveri, who has worked in Samos for nearly seven months, young children in the camp pass the time between scheduled, volunteer-run activities by playing with “whatever they can find,” such as sticks and rocks.

Oliveri says she thinks the older youth will especially benefit from the circus program because they spend most of their day helping their parents with tasks and “don’t get to do a lot of recreational things.”

“They’re not being allowed to be kids a lot of the time just because of the conditions they’re living in,” she adds.

“If it empowers them and teaches them about confidence and putting themselves first … that’s an added bonus that I think is very much needed here.”

Oliveri says Samos Volunteers offers programs for adults, such as language and sewing classes. In addition, young children take part in a “reading circle” in the mornings where they learn the alphabet and numbers in English and in the afternoons, they sing songs and play games.

She says it’s a routine they have come to expect.

“What people needed was a way to combat the boredom and isolation that the camp has and just a way to do something productive with the time while they were here.”

For some, Oliveri adds, that time is a few months – while for others, it can be years.

She says the two-month long circus program, culminating in a show that will be put on by the kids, will be a change of pace that she thinks we will an “absolute hit.”

Shibley, who is graduating with a degree in international conflict studies at St. Paul’s University, says he hopes to also implement conflict mediation skills, such as collaboration, active listening and non-violent communication, into their program.

He adds that the team sees a lot of potential for this “obscure, uncanny avenue for change.”

Hatashita says they plan to grow their program and take it to other countries and to inner-city and northern communities in Canada.