An Ottawa medical researcher is heading a project to see if cutting carbs from the diets of people with type 2 diabetes can improve their management of the disease.

Over the course of their lives, about one-half of all young adults across Canada is at risk of developing type 2 diabetes, the most frequently diagnosed form of the disease. Although the risk can be mitigated by choosing a healthier lifestyle, millions of Canadians still face a high chance of developing diabetes.

Type 1 diabetes is caused by an autoimmune reaction in the body in which the immune system attacks insulin-producing cells in the pancreas. Type 1 is more likely to appear in adolescence and is often related to genetic factors.

Type 2 diabetes can be related to diet and other lifestyle factors, though genetics can play a role in the diagnosis.

For more information about type 1 diabetes, check out our "Lace Up" story.

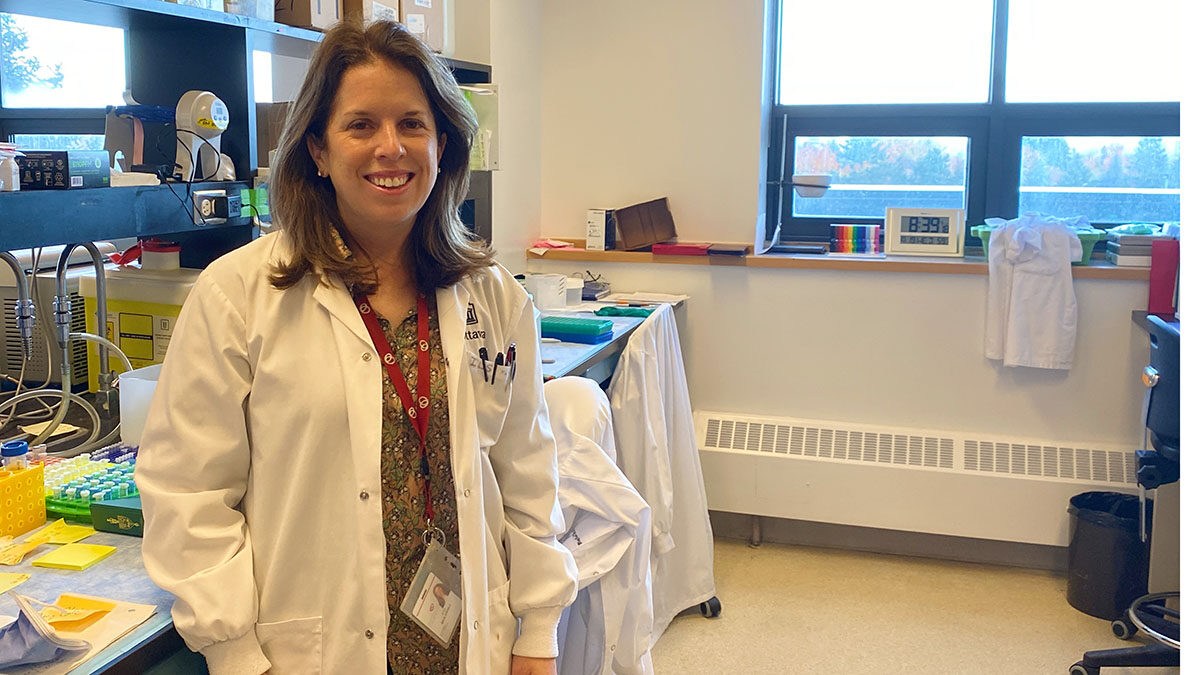

Dr. Erin Mulvihill, an assistant professor and researcher at the University of Ottawa Heart Institute, explained that in type 2 diabetes, the body can produce insulin but it isn’t being effectively responded to. Unlike in type 1 diabetes, where there is no insulin signal, with type 2 diabetes there is an insulin signal but no reception of that signal in the body.

This is why many type 2 diabetics take pills such as metformin or sitagliptin because these medications can help improve that signal.

‘We’re getting better with treatments, but there’s still not a good level of control that they’re able to have.’

— Dr. Erin Mulvihill, professor and researcher, University of Ottawa Heart Institute

With funding from Diabetes Canada, Mulvihill is exploring the impact of high-fat, low-carb ketogenic diets on people with type 2 diabetes. Many people following the popular keto diet in recent years have had success in managing their type 2 diabetes by restricting carbs and saccharides.

Mulvihill wants to understand the impact that very low levels of glucose have on a person’s hormone-producing beta cells. Those cells, according to Mulvihill, are designed to sense glucose and respond to it. If, over a long period of time, they are not exposed to glucose, she wants to see if that will impair their function, or if it will help them to function better.

Mulvihill leads a team of researchers. The group is half-way through their four-year research project titled “Exploring the effects of ketogenic diets on type 2 diabetes.”

“Diabetes occurs because of defects in insulin production in the islets of the pancreas,” states a Diabetes Canada summary of the Mulvihill-led project. “Recent evidence suggests that ketogenic (high-fat, low-carb) diets can be used to treat type 2 diabetes; however,

the effects of these diets on the islets, and whether they actually affect insulin production, are unknown. Our research will evaluate the short- and longterm impacts of consuming a ketogenic diet to treat type 2 diabetes, which will inform on their safety.”

The summary adds that while “ketogenic diets can reduce and stabilize blood sugars,” medical researchers “do not know if they also correct the insufficient insulin secretion that causes type 2 diabetes. This research will either provide patients with the confidence to practice ketogenic diets for their beneficial effects or identify concerns with these diets.”

Mulvihill’s PhD work included researching high cholesterol, a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. However, another risk factor for heart disease and circulatory problems is diabetes.

While Mulvihill got started in diabetes research because of its intersection with her expertise in cardiovascular diseases, she also has friends and family with type 1 or type 2 diabetes.

“We’re getting better with treatments,” Mulvihill said, “but there’s still not a good level of control that they’re able to have.”

Mulvihill is also a professor who teaches other aspiring researchers at the University of Ottawa. She teaches third-year and fourth-year metabolism in the translational and molecular medicine program at uOttawa. She also teaches some graduate courses — one about lipids and lipoproteins while the other is about molecular mechanisms and cardiovascular disease.

Mulvihill and her students’ research on ketogenic diets is considered “preclinical,” meaning it doesn’t directly involve patients.

“We do a lot of work in cells, also in lab animals, and then there are agreements that patients can agree to give samples as part of a clinical study,” she said. Her team then analyzes some of those samples in their lab.

Mulvihill said she’s hopeful that medical science will see more meticulous testing of nutritional interventions to give people more options in their diabetes management.

She added: “We do know that while on a population level, some of these interventions maybe aren’t effective due to adherence,” but noted that there are often success stories, too. “I think that’s what everyone is working towards — just increasing the number of success stories,” she said.

Finally research on the ketogenic diet and diabetes. Type 2 diabetes was very rare 50 years ago. Now it has become the norm. Our carb loaded diets and inactivity are what are causing the huge upswing in diabetes.

I agree, I don’t see why everyone has dragged their feet on proving this works or is a waste of time. Or worse, harmful in the longer run. Government should be testing this as there is little money to be made in having people adjust their ways.

Why the complicated language? Simply put, when you keep inundating your body with sugar and carbs (which turn to sugar), insulin, whose job is to knock on your cell’s door and ask it if it needs sugar, quits because the cells say « no thanks, got enough ». Diabetes 2 is caused by eating too much sugar and carbs. Easy solution. Stop eating sugar and carbs.