Wendy Muckle will readily admit that the work she does isn’t loved by all.

“The reality is that there’s really nobody, myself included, who thinks that supervised injection sites are the best thing since sliced bread,” Muckle says. “It is absolutely understandable that people are against illicit drug use.”

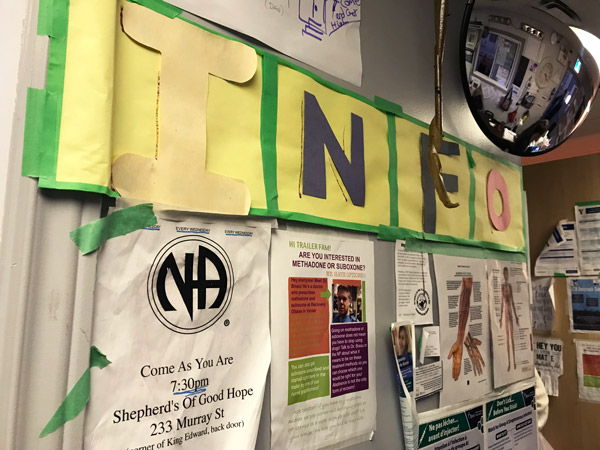

As the executive director of Ottawa Inner City Health, Muckle works to help fund and staff the supervised injection site trailer located outside of the Shepherds of Good Hope on Murray Street. With the site having marked its one-year anniversary on Nov. 7, plans have been made for the program to move from the construction trailer to a larger renovated space inside the main shelter.

“We’ve been completely over-subscribed from the very first day, and that has continued,” Muckle says, adding that the expansion has been on hold since the provincial election this spring.

Supervised injection sites such as the one Muckle helps to run, where illicit drug users can inject drugs in a safer setting using sterile equipment under the supervision of a nurse, have entered a period of uncertainty.

With Premier Doug Ford initially voicing opposition to the sites as a whole, Health Minister Christine Elliott announced on Oct. 22 that the province’s existing “consumption and treatment services” sites would be allowed to remain open if they re-applied for funding. But for now, the province has capped the number of operating sites at 21. There are 18 sites open in Ontario, with three others approved.

“Being forced to re-apply is pretty disappointing, because we’re so busy,” Muckle explains, adding that Ottawa Inner City Health provides site data on its operations to the province quarterly. “There’s nothing in this application form that we did not include in our application a year ago or that they don’t already have.”

Ottawa has four operating supervised injection sites. Along with the trailer at Shepherds of Good Hope, sites are at the Sandy Hill Community Health Centre, Somerset West Community Health Centre and at an Ottawa Public Health clinic at 179 Clarence St.

Rob Boyd, director of the Oasis site at the Sandy Hill Community Health Centre, says it’s business as usual at his site. Meanwhile the site is reapplying for funding. He agrees with Muckle that the re-application process is frustrating. He’s also concerned about the cap on the number of sites.

“If there’s any other community that wants to start one, it would be a matter of taking one away from somewhere else,” Boyd says.

David Jensen, a media spokesperson for the Ontario government, said in an email statement that applications for consumption and treatment service sites will have to satisfy five criteria: that there is a need for a site in the community; that the site will have the capacity to provide adequate services; that the site is far enough away from similar service centres; that the community has been consulted on the site and that the site is fully accessible.

Jensen added that sites will be required to provide information and assistance to users looking to access addiction treatment services, mental health care, housing and other social supports. Approved sites will also be required to submit monthly reports detailing the number of clients, any overdoses that occur, and the number of 911 calls made.

Supervised injection sites have sprung up around the country in recent years in an effort to address a sharp increase in hospital visits and deaths resulting from opioid overdoses. More than 8,000 suspected opioid-related deaths have occurred in Canada between January 2016 and March 2018, according to findings published on the Government of Canada’s website. Of the 1,036 opioid-related deaths that occurred in Canada between January and March of 2018, 94 per cent are considered to have been accidental.

Ontario has not been immune. Emergency room visits related to opioid use in the province spiked in August, 2017, with nearly 1,000 visits, according to Public Health Ontario. The number of monthly emergency visits in 2018 has ranged from 500 to 700.

In Ottawa, Inner City Health’s supervised injection site trailer experienced an average of 785 weekly visitors from April to July, 2018, according to data on Ottawa Public Health’s website. The number of visitors peaked the week of April 23, when nearly 1,000 people visited the site.

“If the supervised injection site wasn’t there, then people would die,” Muckle says. She adds that allowing injections to happen in a safer space under the supervision of a nurse has helped to reduce the size of a “horrific open drug market” operating in the alleys and sidewalks around the King Edward Avenue and Murray Street neighbourhood.

Boyd]

Donna Casey, a program and project management officer with Ottawa Public Health (OPH), says OPH is pleased with the province’s decision to allow supervised injection sites like the one at 179 Clarence St. to continue operating. As the site re-applies for funding, she adds that OPH would be working to improve its on-site resources to refer clients to treatment services, mental health services and social supports. The OPH site has seen 20,000 injections take place since it opened in September 2017, according to Casey.

Muckle does give credit to the provincial government for taking the time to review its decision on supervised injection sites and become educated about the role sites play in reducing overdose deaths. However, she says that the imperfect new system may lead to unintended consequences, particularly with the 21-site cap that could see cities competing for limited resources.

“It’s really concerning to see the most vulnerable citizens in our communities basically being pitted against each other for survival,” she says. “That’s a pretty distressing situation.”