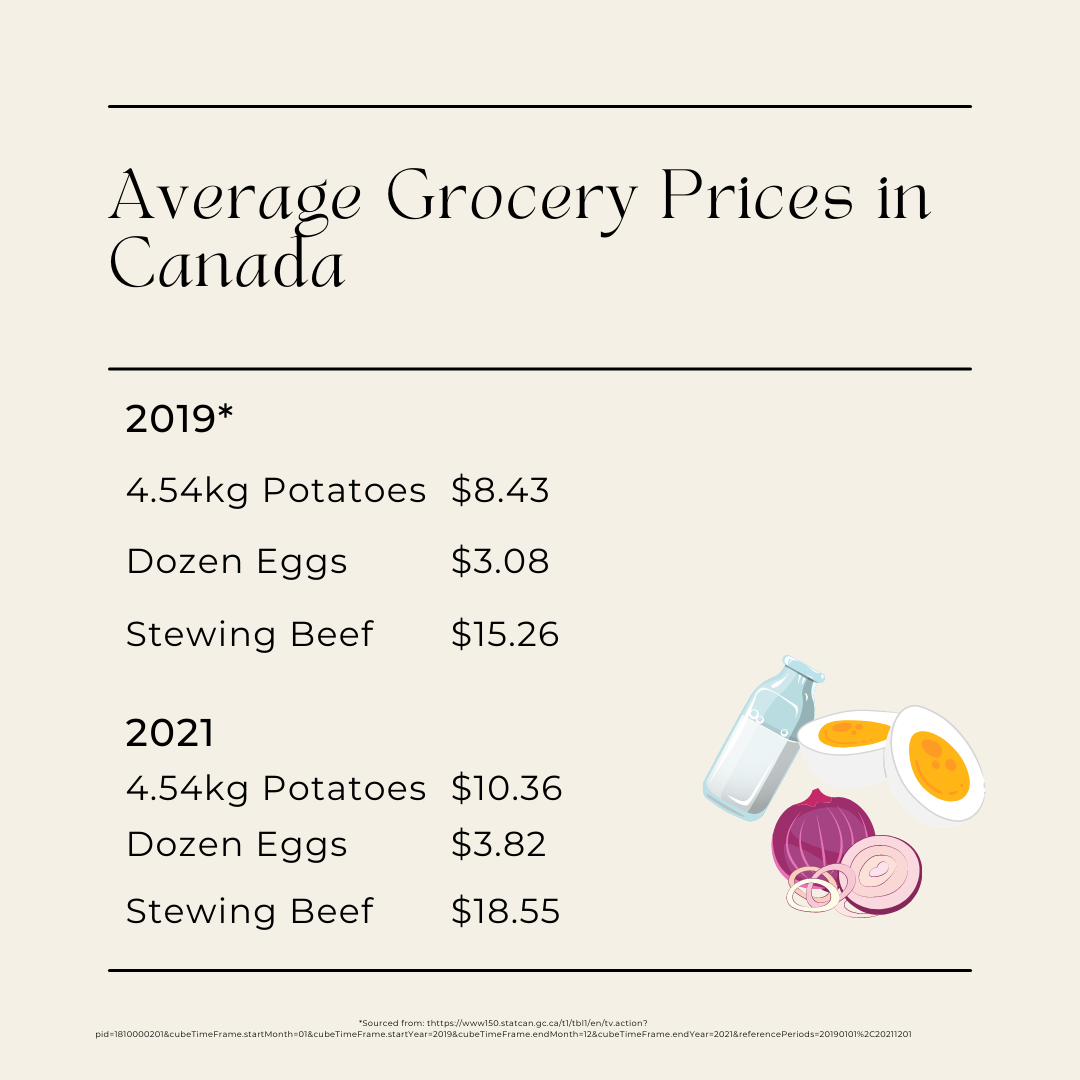

With inflation hitting highs not seen in more than 30 years in Canada, many fear that already high levels of food insecurity will only worsen over the coming months or more.

“It’s come to the point where I have to spend over 50 per cent of my paycheque on food,” said Cydney Cantello, a fourth-year student at Carleton University. She works part-time at a local restaurant while attending classes.

“I’m 22. I shouldn’t be worrying about paying for food. It’s a basic right.”

Experts say there are many interrelated factors contributing to skyrocketing prices for food and other essentials. According to Food Secure Canada (FSC), about 4.4 million Canadians are food insecure. As a result of the pandemic, many Canadians are out of work or experiencing the effects of supply-chain issues.

“Food security can mean a lot of things,” said Alyssa Gerhardt, a Ph.D. student in the Department of Sociology and Social Anthropology at Dalhousie University.

Food security encompasses affordability, accessibility and access to cultural foods, she says. COVID-19 restrictions on cross-border travel, store capacity and rapidly changing demand have all played a part in food shortages and increased food costs.

Gerhardt says that since the start of the pandemic, many groups who had not felt the effects of inflation as harshly as others are beginning to be affected by the rapidly rising costs of living.

“Something unique that has come out of [this]: middle-income earners are sharing their feelings around budgets. It’s something we can all relate to,” she said, adding that overall these effects will not be felt evenly.

“It’s also important to recognize that certain groups are disproportionately affected by food insecurity. As food prices rise, it’s going to separate those social inequities.”

COVID-19 has put additional strain on various aspects of the supply chain, leading to basic needs being inaccessible for many. Inflation, poor weather and trucker shortages south of the border have drastically affected the Canadian economy and access to food.

“The labour shortage is playing a huge part in the supply chain,” said Elizabeth Raman-Grubbs, a graduate from MIT’s Masters of Supply Chain Management program.

“The trucking shortage that has been ongoing since before 2020 … it’s only been exacerbated by the pandemic,” she said.

Rising grocery prices have many moving parts, but locally, the effects are acute.

In Ottawa, food prices have been steeply increasing for years even before the pandemic shutdowns. But the impacts vary across the community.

According to a 2012 report from the Ottawa Food Action Plan, 22 neighbourhoods in the Greater Ottawa Area are considered food deserts. Pre-pandemic demographic data from 2019 show that little had changed.

“It feels like the odds are stacked against people my age,” said Cantello.

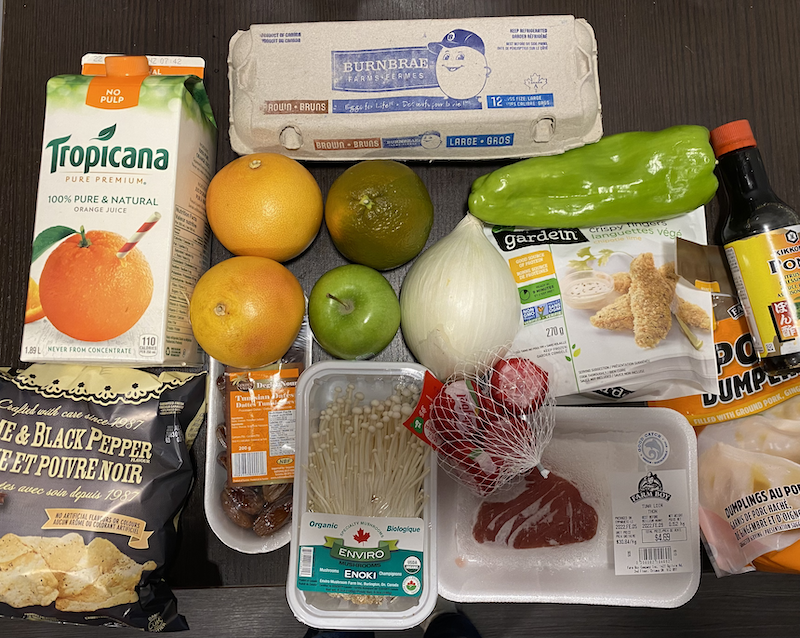

“Not only are grocery stores in Ottawa inaccessible location-wise, but many people can’t afford the food being sold, so have to find alternative ways to feed themselves.”

She said that the Carlington neighbourhood she lives in is considered to be a food desert.

“Right now, the closest grocery stores are Farm Boy and the Independent, both of which are very expensive,” Cantello said. She explains that while she hopes more resources will come to her neighbourhood, she fears that they will be unaffordable too.

“I’m worried that these condos will lead to more ‘luxury resources’ being developed,” she said, referring to some. nearby 60-storey condo buildings being developed by Claridge Homes.

“We need more grocery stores in Carlington, but we don’t need stores like Whole Foods or Pusateri’s.”

Perhaps not surprisingly, the Food Insecurity Policy Research centre at the University of Toronto links food insecurity directly tied to income. In a policy document, they conclude that the “poverty reduction strategy introduced by Newfoundland and Labrador in 2006 demonstrates how improving the benefits received through social assistance can have a substantial impact on food insecurity.”

This is something that many can relate to, though it’s not a simple policy fix.

“Access to resources is far from equal in Ontario,” said Cantello.

“Almost everyone is closer to being without food than they are to being a millionaire, so I think it should be a more pressing issue for more Canadians.”