With COVID-19 forcing people to practise physical distancing, a pet can make a big difference in terms of emotional support.

Fortunately, while the novel coronavirus is believed to be a zoonotic disease – which means it was transmitted from animals, presumably bats, to humans – research shows it’s very unlikely people can get it from their pets.

And despite some initial concerns about pet-to-human transmission of COVID, being forced into quarantine has spurred Canadians to adopt and foster pets at record rates. Furthermore, most animals not only support our mental health, they will likely be key to ultimately beating the virus. Studying animal models is contributing towards vaccine development.

While there is no evidence people can get COVID-19 from their pets, myths persist that negatively affect animal welfare. Many concerns emerged in late February after a report from Hong Kong confirmed the “first known case of potential human to animal” transmission – though the case suggested a weak strain of the virus had moved between owner and dog.

Initial fears

“This first case sparked fears among the public, resulting in acts of animal abuse by people who believed that pets might start to spread the virus to people,” noted a study published online in the journal Forensic Science International by U.S. veterinary pathologist Nicola M.A. Parry. “One group known as the Urban Construction Administration announced it would kill cats and dogs found outdoors, to prevent transmission of (COVID-19). And even officials in Hunan and Zhejiang provinces announced they would begin killing pets that were found in public.”

Organizations such as Humane Canada in Ottawa, which represents the country’s humane societies and SPCAs (Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals), worried about what actions pet owners would take, both because of possible fears of COVID-19, as well as severe financial setbacks from not being able to work.

“We expected that there were going to be more animals surrendered to shelters because as people started to lose their jobs, and have their incomes compromised, we were expecting them to not be able to afford veterinary care, food and medication for their pets,” said Natalia Hanson, marketing and communications co-ordinator for Humane Canada.

Humane Canada made sure the public was provided with accurate information about the pandemic. As more people were forced to isolate themselves in their homes, it turned out to be a silver lining for human-animal relationships.

“Once people found themselves being home and having more time, they started flooding humane societies and SPCAs with requests for adoption and fostering,” said Hanson.

For example, Hanson said the Lincoln County Humane Society in St. Catharines, Ont. reported that normally 30 people reach out when they issue a call for foster families. Towards the end of March, that number had jumped to 400.

“There’ve been all sorts of interesting fostering programs that have crept up,” said Dr. Ian Sandler, the CEO of Grey Wolf Animal Health and a member of the Canadian Veterinary Medical Association’s national issues committee. “Many of the rescue associations and shelters are, or have been, emptied because Canadians thought this would be a great opportunity to either foster or adopt a pet, and in many ways, it’s been very successful.”

Of course, while this rise in adoptions and fostering has been positive so far, Hanson said people must also consider what will happen after the pandemic.

“We want to make sure people understand that adopting an animal should never be an impulsive decision,” said Hanson. “They need to keep in mind that eventually one day they’ll go back to work, to school or whatever they were doing before.”

Hanson and her colleagues expect that more pets will be relinquished because of their owners’ financial state following the pandemic.

“Not everybody is financially prepared to continue not being at work,” she said. “While some people may be going back to work and getting back up financially speaking, others may have lost their jobs permanently.”

Vets on the front lines

For veterinarians, Sandler said the pandemic has put them on the front lines.

“The Canadian Veterinarian Medical Association led the way with a number of different initiatives. We worked with many of the registers on all of the provincial associations,” he said. “We helped co-ordinate some of temporary changes around things like telemedicine and the dispensing of certain drugs remotely for veterinarians to ensure that patients across Canada could be taken care of and maintained.”

The association also provided personal protective equipment and even ventilators to emergency clinics and hospitals.

“We’ve ensured that the procurement of human ventilators that we’re using, or being used in veterinary medicine at emergency clinics, referral clinics and teaching hospitals, were allocated to provincial hospitals,” said Sandler.

When society returns to normal, the events of the last few months will also demand new approaches and solutions.

“We want to ensure that we’re working with government agencies around the appropriate supply chain of food, essential medicines, veterinary medicines and essential services,” said Sandler. “We want to make sure that even if there’s a second or third wave, we can continue to provide care for Canadians on all different levels.”

Sandler also said it’s important to co-ordinate efforts with governments within Canada and abroad.

Veterinarians and animal science also have a crucial role to play in human health during the pandemic. For example, researchers are using animal models to provide vital information for developing vaccines.

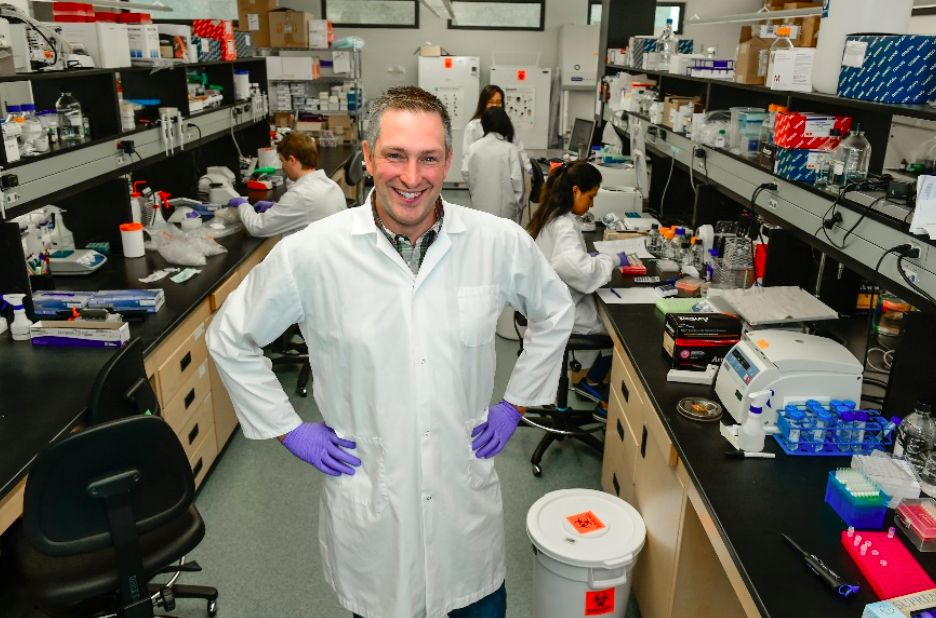

Darryl Falzarano is a researcher with the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization-International Vaccine Centre (VIDO-InterVac), an organization from the University of Saskatchewan that researches and develops vaccines against both human and animal diseases. Falzarano and his team were awarded $1 million by the federal government as part of a research initiative to address the COVID-19 pandemic.

Falzarano is an expert in coronaviruses such as Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS). These viruses are closely related to COVID-19 and are also considered zoonotic diseases, but are much less widespread than SARS-Cov2 – the virus that causes COVID-19.

There have been more than 10 million confirmed global cases of COVID-19 and more than 500,000 deaths.

Falzarano and his team at VIDO-InterVac are one of many research groups, in Canada and around the world, working to develop a COVID-19 vaccine. By researching and testing animal models such as ferrets, Falzarano and his team can better understand how a virus is transmitted, how it affects its hosts, as well as develop a vaccine.

According to Falzarano, their research has shown positive results and they could soon be ready for clinical trials at the Canadian Centre for Vaccinology in Halifax.

“At the moment,” said Falzarano, “we are planning to start a phase one clinical trial, provided everything continues to go well in the fall of this year.”

[…] Credit : capitalcurrent.ca […]

[…] — to capitalcurrent.ca […]