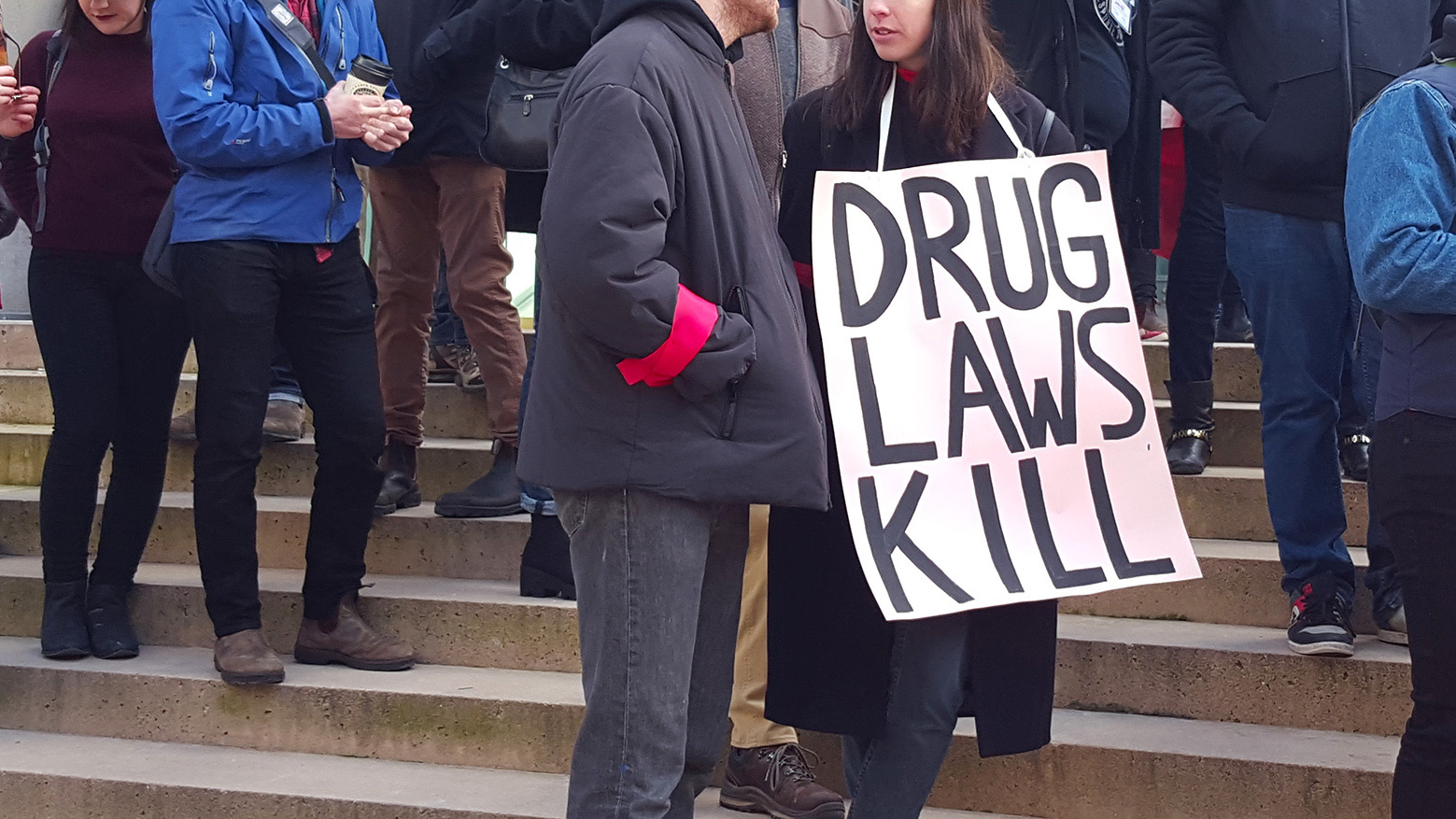

Canadian police chiefs have proposed ending criminal penalties for personal drug use, but drug policy experts say there’s a need for more urgent, concrete action as the opioid epidemic worsens under COVID-19.

The Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police called for the decriminalization of simple possession of illicit drugs in a report released July 9. The association suggests fines and alternative measures such as supervised consumption sites, safe supply initiatives and diversion programs.

“One of the main drivers was what we were seeing with the opioid crisis and the thousands of Canadians who are dying,” said Police Chief Mike Serr, co-chair of the CACP’s special purpose committee on the decriminalization of illicit drugs.

He added that another factor in the decriminalization push was that “the tools and the enforcement strategies that we’ve put in place have not been effective.”

Drug policy experts say the idea is a step in the right direction, but that CACP’s proposed changes to current laws need to be acted upon quickly as the health advocates have witnessed a spike in overdoses across Canada during the pandemic.

A worsening epidemic

The opioid crisis has killed more than 15,000 Canadians, according to Sané Dube of the Alliance for Healthier Communities, “a vibrant network of community-governed primary health care organizations” in Ontario.

“It’s a really severe crisis (and) addiction is very much a health issue,” said Dube. “Criminalizing people for drug use was part of the war on drugs and we know that the war on drugs has failed — it has not reduced the number of people who are using drugs and it has not reduced the harm.”

Dube added: “What the war on drugs has done is really just increase the number of people who are incarcerated and take help away from people who need it.”

The police chiefs’ report is in line with a recognition that substance use is a public health issue rather than a legal, criminal one, marking a win for advocates who have been calling for this approach for years.

“We do welcome the police coming on board,” Dube said. “And, well, of course it would have been great if this could have come earlier.”

When it comes to getting the government involved in rewriting Canada’s laws, Serr said he remains optimistic.

But for Caitlin Shane, a drug policy lawyer, the present laws need to change immediately.

“For years and years we’ve been hearing very clearly from the community and from people who use drugs that criminalization of simple possession is undermining public health, and is frankly killing people,” said Shane, who works for Pivot Legal Society in Vancouver.

“What I think we’re worried about (with the chiefs’ report) is that we’re going to see more heel dragging and that we’re going to see more inaction, which is costing lives.”

A legacy of discrimination

“What we see in the context of the war on drugs is vast numbers of people of colour being targeted, stopped, and criminalized for simple drug possession,” said Shane. “And these are charges that are not typically laid against white folks, wealthy folks, people who have access to the privacy of a home, people who don’t have to rely on a street-level source of drugs, and so it really results in a very unequal landscape.”

Canada’s drug policies have historically been rooted in racism, said Scott Bernstein, director of policy at the Canadian Drug Policy Coalition, referring to the early 20th-century opium panic that led to the country’s first anti-drug laws.

“The laws went after smokable opium, which was used primarily by the Chinese but not opioid pills or other forms that were taken by white people at the time,” said Bernstein.

“A two-tier system was created, particularly targeting racial populations, and that’s something that sort of carried on — using drug policy as a form of racial and social control,” he said.

With the present opioid crisis, Shane said the representation of people in jail for low-level offences remains “wildly disproportionate.”

The case for defunding

The issue, said Shane, is related to the growing calls for police defunding since the Minneapolis police killing of George Floyd on May 25 and the subsequent anti-racism protests in the U.S., Canada and elsewhere.

“You take away funding for the enforcement for (low-level offences such as) simple possession and put it toward better initiatives to support people who use drugs,” said Shane. “But the report that the CACP released specifically mentions that the decriminalization that they have in mind cannot include the defunding of police.”

Amidst the growing discussion around defunding police budgets, advocates see the move for decriminalization as a good place to start, but the CACP maintains that funding requirements for forces won’t change.

“We in our statement said very clearly that (police) still have a very large role in going after those who produce, import and distribute drugs on our streets,” said Serr. “That’s a huge undertaking and it always will be.”

Serr said police will remain the first point of contact as the “boots on the ground” directing people to health and treatment services all year round.

However, drug policy experts don’t want police to remain involved, especially as frontline aid for people dealing with personal substance use.

“Police cannot be the ones who are serving as the gatekeeper of those services, so long as people have the histories that they do with police — which is, you know, a racist, classist history,” said Shane. “They’re still going to fear police interaction whether or not there’s a criminal sanction or administrative sanction at the end. Police need to be taken out of the equation and that means defunding.”

The release of the police chiefs’ report does help open up a dialogue about what the future of policing and public health will look like in Canada.

Bernstein said there’s a chance now to get police out of the process of dealing with individual drug use.

“In many ways,” he said, “we have an opportunity to restart and put people in the position who maybe are peers or people who have experience with drug use as frontline intervenors.”

[…] harm reduction services, a spike in overdoses had been expected by experts. The CACP called for a decriminalization of simple possession for illicit drugs earlier this month in response to the worsening opioid epidemic in […]