In May, Quebec’s Coalition Avenir Quebec government tabled Bill 96, an act respecting the French language in the province.

Upgrading the landmark Bill 101 — the province’s 1977 French-language charter — Premier François Legault aims to set limits on the number of children receiving English-language education and impose rules regarding appropriate knowledge and use of French in businesses and workplaces.

The goal is to increase the use of French in public.

As part of the Bill 96 discussions, Legault recently introduced an exception for “historic anglophones” — a new label that has since divided the province’s linguistic community.

Outlined in Bill 101, an “historic anglophone” is defined as anyone who learned English in school or went to an English-language school in Canada. Legault says this categorization allows for the government to define which groups of people are eligible to receive provincial services in English.

To some, it may seem as though this category aims to create accessibility for Quebec’s language minority, but it’s not that simple. In reality, the label has a number of unique implications for those in the province.

Some critics call it “patronizing”, and others “self-serving”, but those tuned in to minority language concerns generally agree that it is likely not the right approach.

As a Quebecer, and one with a unique perspective on this latest development, I’m of the view that labelling individuals “historic anglophones” based on schooling not only excludes anglophone newcomer families, as well as those who prefer to access services in English, but also puts Quebec identity on a continuum.

Flawed definition

Language has long been a hot topic in our province, and a dividing line for staunch advocates of French-language protection and the defence of minority language rights.

An open letter released Oct. 29 by the Quebec Community Groups Network (QCGN) — an advocacy organization representing Quebec’s English-speaking community blasted the premier’s decision to adopt the term “historic anglophone” citing the fact that the community should get full rights to participate in Quebec society in any way it sees fit.

As a Quebecer, and one with a unique perspective on this latest development, I’m of the view that labelling individuals ‘historic anglophones’ based on schooling not only excludes anglophone newcomer families, as well as those who prefer to access services in English, but also puts Quebec identity on a continuum.

“We are not some folkloric historic group,” stated the release. “We are full-fledged Quebecers who are committed to building an inclusive Quebec where French is the common language.”

I sympathize with some of the frustration. This system seems flawed in a number of ways.

I attended English-language school, and was permitted to do so because my parents went to English-language schools in the province, like most of my community in Montreal’s West Island. I am also bilingual. I participate in Quebec society in French and routinely receive provincial services in French by choice and convenience.

In line with other critics on this issue, I’m afraid this category will limit who is considered part of the anglophone community — excluding those who might need (and want) English services the most.

In addition to denying eligibility for English services to anglophone individuals born in another country, the Quebec Community Groups Network estimates that the category removes the right to receive English services in health care from up to 500,000 English-speaking Quebecers.

“It is utterly divorced from our community’s self-identification,” states the QCGN. “The attempt to create categories of citizens who are eligible for certain services is deeply troublesome from a public governance perspective. Minorities define themselves; they are not defined by the state . . . The expanded use of this category is offensive.”

Practically, there are also challenges in verifying if someone is a “historic anglophone”. Liberal finance critic Carlos Leitão, a former provincial finance minister, questioned the government’s plan, asking if a “secret password” or “secret handshake” would be required to confirm someone’s “real anglo” status when seeking English services.

Discounts Quebecers’ rights to self-identification

For those outside of Quebec, the debate might understandably be confusing. Why does any of this really matter? Why do these labels get people so angry? Why is language so tightly tied to identity?

It’s important to understand that in Quebec, language is our major dividing line. It gets people riled up, defensive and highly politicized.

Sometimes, I find it odd the extent to which people care — including me — about bills and amendments to language laws, particularly since I view the strength of the French language as part of our province’s unique society and culture. On the other hand, such classifications have the ability to discount the fact that I — like many other bilingual Quebecers — have deep roots and identities attached to Quebec, irrespective of our mother-tongue.

For my family, there are only a couple of generations of anglophones. My grandmother — and all of her ancestors before her – spoke French. Originating from the regions of Brittany and Lorraine in France, my grandmother’s family can trace their ancestry to the first settlers of Nouvelle France who came to Montreal and Quebec City in the 1600s, serving as merchants, officers and even the pioneering “filles du roi.”

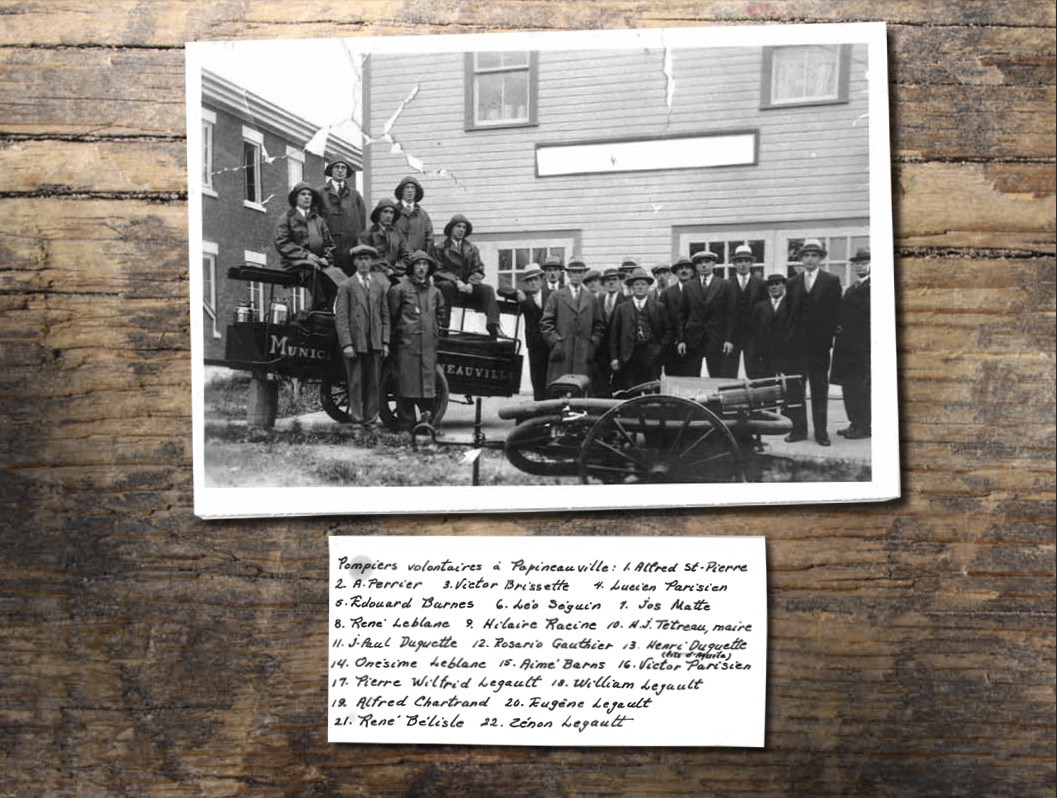

My fourth great-grandfather, Benjamin Perrier (second from left) was born in Quebec’s St. Joachim Parish, a municipality just 10 minutes away from my childhood home. Born in 1812, he served as a volunteer firefighter in Papineauville. (Photo courtesy Ancestry.ca)

Although the extent of my family’s French-Canadian heritage was largely unknown for most of my life, according to my ancestry, on paper, I’m anything but a “historic anglophone”.

This personal anecdote is just meant to show how irrelevant schooling is in defining someone’s relationship with the province.

From my experience, many anglophone Quebecers struggle with their identity. That is part of why these categories might be harmful — alienating certain groups, making them feel different from the rest of Quebec society.

Ultimately, being an anglophone should not make someone any less Quebecois. But the “historic anglophone” definition proposed under Bill 96 brings with it that connotation. It sends the wrong message about identity, inclusion and self-identification — arbitrarily deciding who does and does not have the “right” to receive English services, with little consideration of an individual’s language needs, origins or ancestry.