October is Islamic Heritage Month in Canada, when Muslim congregations across the country hold events to celebrate and explain Islam to the wider community.

But while Muslims are grateful to share the details of their religion, many say such events are only part of what’s needed to reduce the stigma adherents often face.

According to the Ottawa Muslim Association, there are 40,000 Muslims in Ottawa. The city also has 44 mosques and Muslim community centres. There are about 1.15 million Muslims in Canada.

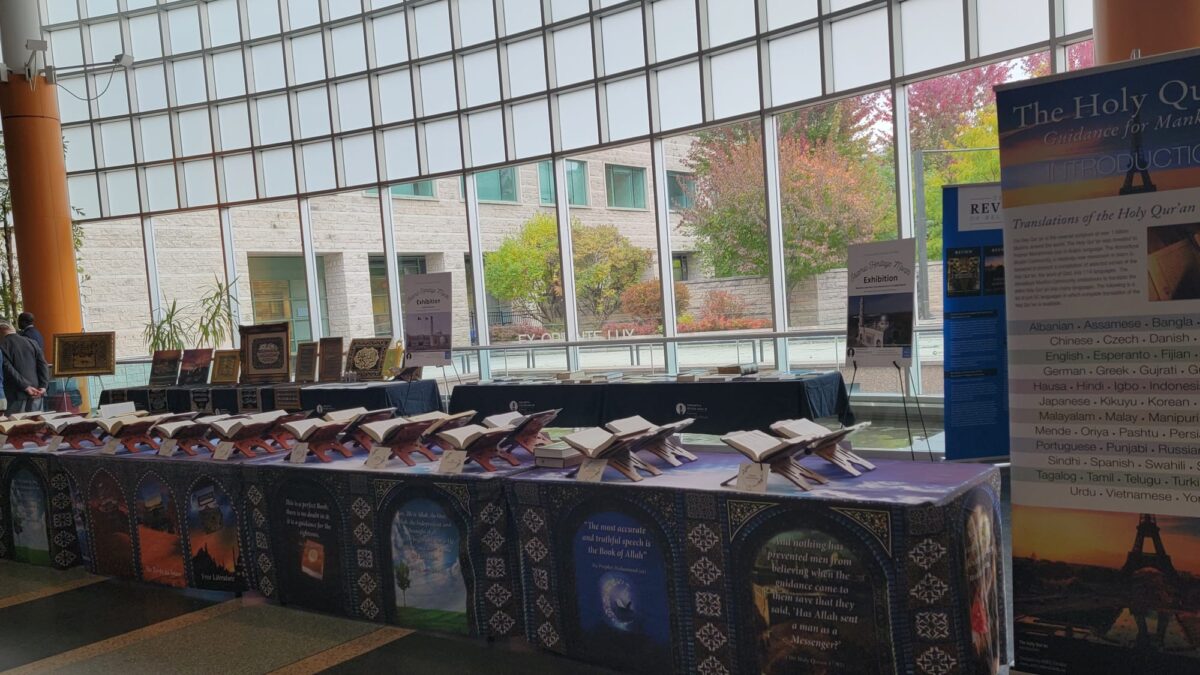

Many of this year’s events have been held in person, after two years of virtual displays only. One recent event, an Islamic exhibition held by the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jama`at Canada, took place at city hall earlier this month.

London-Fanshaw MP Lindsay Mathyssen, who took part, said she found the displays helpful. For instance, “they had all kind of different versions of the Qur’an; different regions would have different translations.

“They had some traditional dress. They had some information about important figures within the Muslim community around the world who had contributed to science, to math.” The invention of algebra was one example she cited. Mathyssen is co-chair of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Friendship Group.

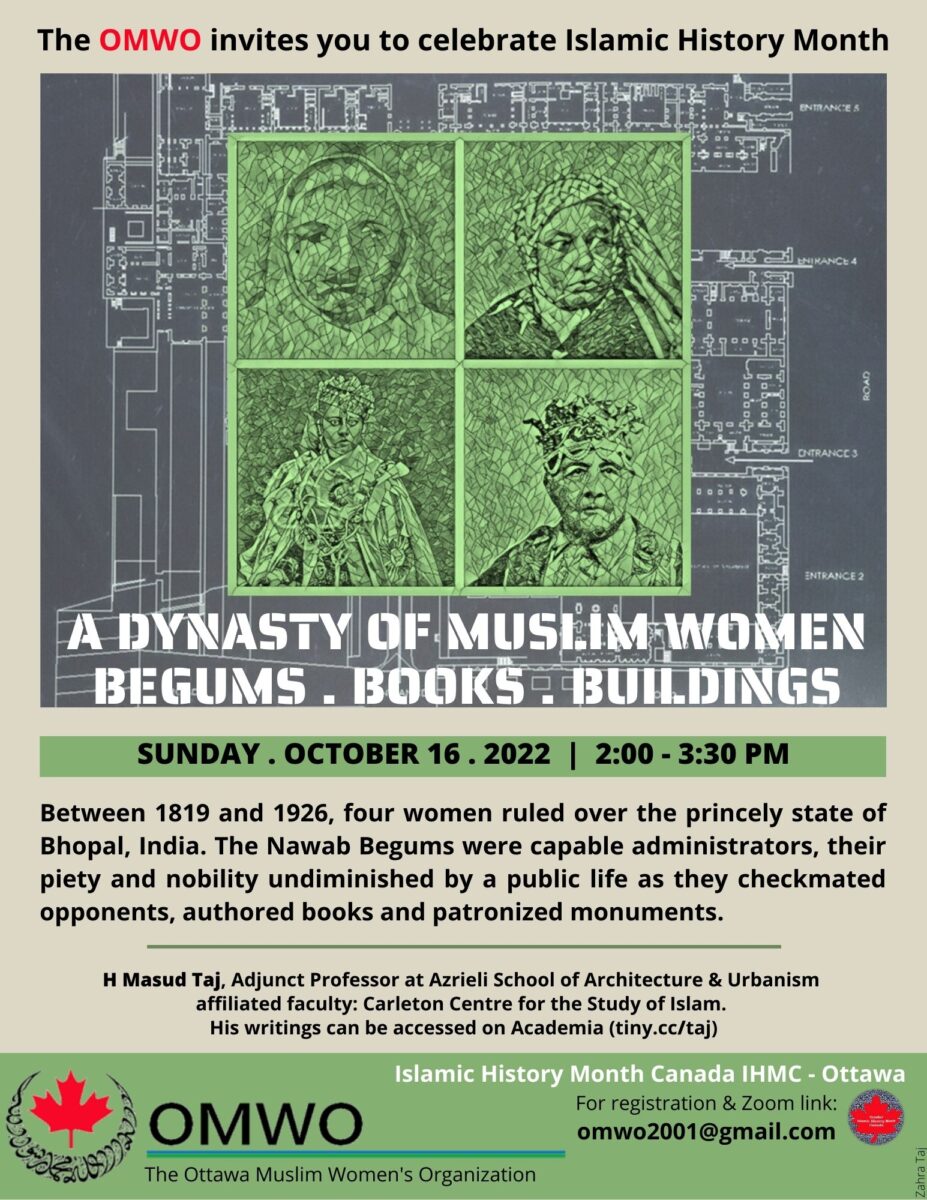

Monia Mazigh, secretary of the Ottawa Muslim Women’s Organization (OMWO), is among those who think that while such events are worthwhile, more must be done to fight the stigma Muslims face.

“In a time where there is increasing [incidents of Islamaphobia], I think it is very important. … But there are other measures that should be taken as well, in parallel with having the Islamic Heritage Month,” she said.

She said she would like students in all levels of education to be taught about the importance of Muslim contributions to Canadian society, for instance, as well as being taught how to help counter Islamophobia.

Mathyssen said education was one of the calls to action created during the National Action Summit on Islamaphobia, held in Ottawa in 2021.

“I think that we have to do a lot better with the education piece,’ said Mathyssen, “it can’t just be off to the side … it has to be a part of curriculums in schools. It has to be more out there for people to actually see it and witness it and take part in it and experience it.”

She also cited continuing efforts in Parliament to adopt a bill that would combat online hate.

Other challenges include Quebec’s law banning the wearing of religious symbols by some public servants, such as teachers, police officers and others, at work.

“By banning (people with hijabs) from working (in the public sector) we are really keeping them economically disadvantaged, we are keeping them vulnerable right? Marginalized. So I think we don’t need those kinds of laws,” said Mazigh. “We need more policy that targets the discrimination.”

Making education on this subject a normal part of schools’ curriculum and not just part of monthly commemoration events would be one step closer to reducing Islamophobia in Canada, Mazigh believes.

Faheem Affan, one of the organizers of the city hall exhibition, said that exhibitions like these help highlight a positive image of Islam in contrast to the negative news often heard about the Muslim community.

“There’s more in media about the negative of Islam than the positive,” said Affan. “Doing small things like [this exhibition], we are actually going to the general public and showing them what Islam is, how peaceful this religion is and how all Muslims are peaceful, good citizens as well, and they’re always there to help humanity.”

A full list of remaining events for the month is available on the Muslim Link website

What’s the problem?

Trees are more important today than ever before. More than 10,000 products are reportedly made from trees. Through chemistry, the humble woodpile is yielding chemicals, plastics and fabrics that were beyond comprehension when an axe first felled a Texas tree.