Every immigrant knows what it’s like to be caught between two worlds. Growing up in one country and then assimilating to another often creates a dual identity, making you not quite one or the other. This can make you question yourself and your place in the world. You ask yourself where is home? Where do I belong? Will the people around me ever fully accept me?

When it comes to visualizing this dual identity, I tend to think of it in terms of strings — you’re born with one that ties you to your old life and then given the other, tied to your new life. A string for the past and a string for the future. Upon moving, most immigrants are often faced with two choices: to cut one string or to juggle life tethered to both.

I didn’t understand the consequences of it at the time, but I made a decision about my identity that would impact not only my relationship with my past, but my relationships with my family and friends. And it would redefine my identity.

I raised the string tying me to my old life and placed it between the sharp, severing edges of scissors.

Before the move

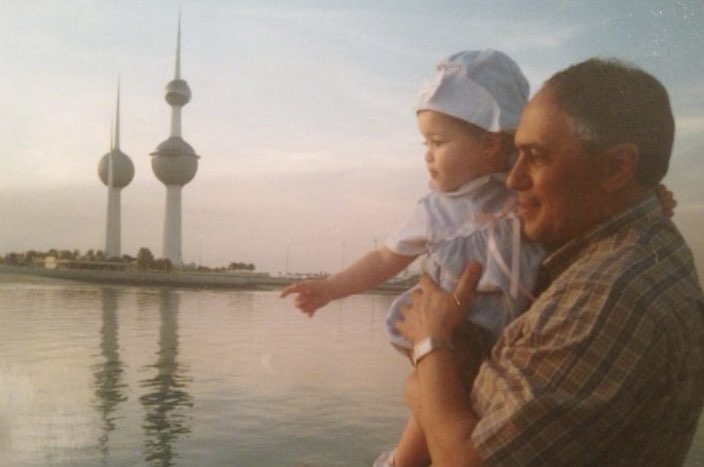

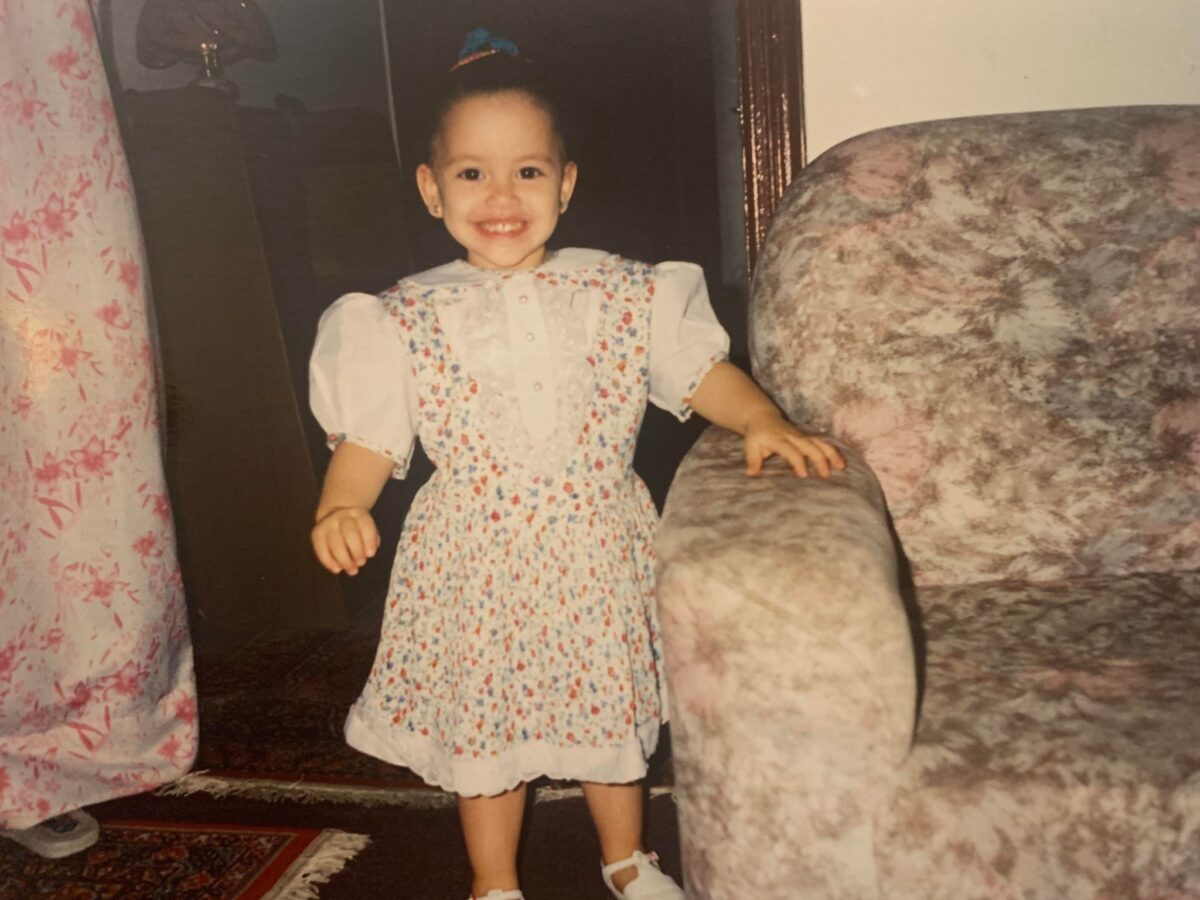

I was 11 when my father announced that we would be moving to Canada. I had been living in Kuwait my whole life prior to this and had only caught glimpses of the alluring Western world through colourful depictions on Disney Channel and action-packed Hollywood movies.

Needless to say, 11-year-old me was very excited. But, being as naïve and sheltered as she was, she didn’t know just how big a change this was going to be.

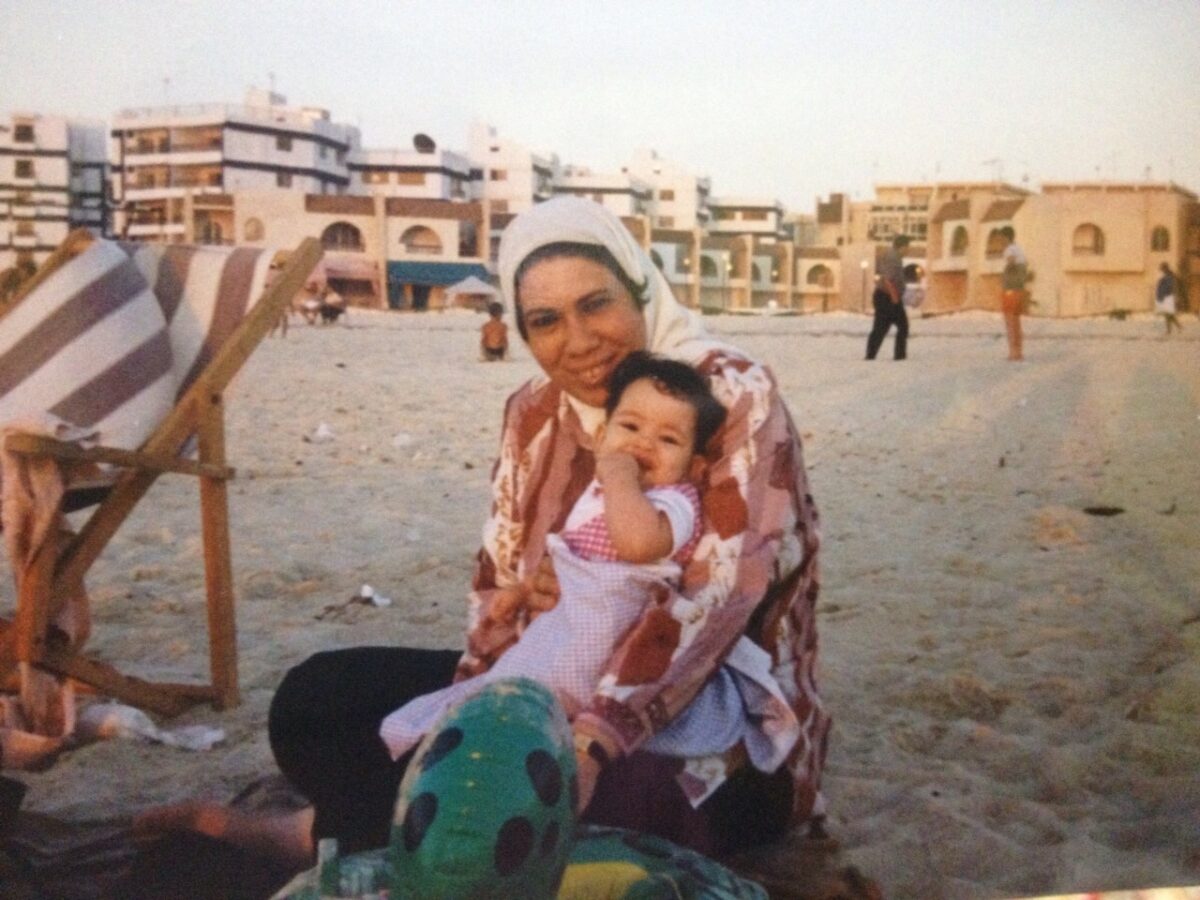

As an Egyptian family in Kuwait, we were living very well. My father was a head dentist at his government health clinic and my mother was a teacher at a reputable English private school — where my siblings and I were privileged to be enrolled. Surrounded by people who spoke the same language, celebrated the same holidays and had the same values, we never questioned our place in the world or where we belonged.

Then, in August 2008, we said goodbye and packed our bags for Mississauga, Ontario, setting off to a world that was seemingly full of possibilities. It was supposed to be a temporary change, long enough for us to get a Canadian education and citizenship — both very valuable assets in the Middle East — then return home.

Fourteen years later, we are still here. We’re the same people, yet we’re almost unrecognizable from the ones who first stepped off the plane so long ago.

The adjustment

The culture shock hit us hard. We went from a family with many connections to almost none. My parents went from respectable members of their community to outsiders with strange accents and a suspicious Islamic background.

Then there was us: my younger siblings and I adjusting to a new school environment. Our peers didn’t look like us. They weren’t in uniforms the way we were used to and they made a lot of pop culture references we did not recognize. They listened to explicit music and were much more uninhibited. It didn’t take long to realize that religious values weren’t as ingrained into people’s minds here the way they were back home.

The culture shock hit us hard. We went from a family with many connections to almost none. My parents went from respectable members of their community to outsiders with strange accents and a suspicious Islamic background.

While this made me wary, it didn’t stop me from approaching it with the nervous excitement that only a child can have. Of course, the more I tried to acclimate, the more I felt a telltale tug in my chest coming from an unknown place behind me. When I stopped to turn around, I realized my past string was earnestly pulling me back to everything I had been taught. I could almost hear it, urging me to be careful and not to forget who I am.

But the more I tried to fit in — wear the same clothes, act the same way — the more I began to resent this string pulling me to the past. The people here are so free, I thought. They’re not as accountable to their faiths, their families, their values. They didn’t even have curfews. Why can’t I be the same? My future string was pulling me to a life of freedom and possibility, but I couldn’t pursue that if my past was holding me back.

These thoughts worsened when people’s contempt towards my background became clear. People yelled at my hijab wearing mother to get out of their country. They made 9/11 jokes about how Arabs should never be on planes. My resentment grew, until the tugging of that past string became unbearable. It was no longer the product of pride, but shame — and I was tired of being held back.

So, around the time I entered high school, I turned around, teeth bared, and severed it.

The cost

Moving to another country with a different language and culture is stressful. That stress has ways of manifesting in interactions between people in the worst ways. When you ignore the warning signs, you don’t notice the fractures until it’s too late.

My dad continued to work in Kuwait for the first few years whiles the rest of us stayed here. Canada doesn’t recognize or accept international degrees, so it was the best option he had to continue supporting us. However, after a few years, the isolation weighed heavily on him and he retired and came to live in Canada with us.

He found children who were no longer in tune with their religion, who had lost their ability to speak Arabic fluently, and who acted and dressed in a way he didn’t recognize. He could see that each of us had cut the strings of our past.

This reality was hard for him to accept. It was harder for my mother, who had watched it all slowly happen with no way of stopping it. I’m sure they both had the same thought: This wasn’t supposed to be the plan. The citizenship papers had taken too long and the consequences were clear and irreversible. We could see the regret descend upon them, deep-seated and disquieting, as though wishing they could take it all back.

A lot of people tend to see immigrants as opportunistic job-stealers looking to live easy lives, but the truth is that immigration is not easy. It is a trying and taxing process that carries a heavy toll that follows you for years.

Things are different now. Rather than a festive family that regularly entertains (like we used to), we’ve become withdrawn. We don’t understand each other or the people around us; we don’t even understand ourselves half the time. Assimilating is supposed to deepen our connection here, but it only seemed to have turned us into a mirage: visibly here and yet … not quite.

Our time in Canada, though blessed in many ways, wore at our edges with every conflict and struggle. My siblings and I in particular learned what it was like to grow up too soon, surrounded by peers who could never know what it was like. They had families to celebrate holidays with, parents with stable jobs, homes they could call theirs — homes they grew up in. They had stability, security, comfort in the knowledge that whatever happened, things would be OK.

A parents’ sacrifice is usually a major point of reflection for immigrant children. They give up the comfort of their hometowns, friends, jobs, and culture in favour of giving us a better future. Now we take care of them as much as they’ve taken care of us, because they still get confused here sometimes.

My siblings and I are chasing our futures in university now, but we often wonder if the privileges we were granted in Canada were worth the costs — emotionally, culturally — on our family.

We made the choice to cut the strings to our past, but now whenever we look back and ask each other if we would’ve been happier back home, the answer is always a resounding yes.

A lot of people tend to see immigrants as opportunistic job-stealers looking to live easy lives, but the truth is that immigration is not easy. It is a trying and taxing process that carries a heavy toll that follows you for years.

Long after I cut the string to my past, I could still feel its absence echoing in my heart. It used to be reliable and ever steady, tying me to a simpler life filled with laughter and good memories. I took that string for granted before. I didn’t understand it, even hated it. But now, with every bone in my body, more than anything, I want it back.

Looking ahead

I haven’t been back home in eight years, but I will return some day. I want to reconnect with my family, my past, and hold my dual identity with pride. Not everyone gets to say they are part of two worlds, and that is a valuable experience — I understand that now.

My future lies in Canada, as I’ve integrated in a way that can’t be undone. But as I take the values this country has taught me, such as independence and freedom, I am beginning to remember the things Egypt has taught me, too — family and community. I know now that I don’t have to be connected to one string or the other; I can honour the beautiful experience of having both.

I severed the string to my past long ago. But now that I’ve begun to meet people who are like me, who carry the same experiences but do so with pride, I’ve decided to turn around and pick up that discarded string again. It’s weathered and frayed, but I am delicately tying the knot to bind us together again, so that I may finally move forward to the future as a whole person — connected to the past and ready for the future.