From meditation to yoga, astrology and beyond: many people coping with pandemic challenges are turning to alternative and secular forms of spirituality as their anchor in a sea of endless stressors.

Since the COVID-19 crisis began nearly two years ago, engagement in spiritual practices has increased, especially among women, Generation Zs and Millennials. Google Trends suggests that search results for astrology, tarot and crystals hit five-year peaks in 2020 and 2021 respectively.

But advocates say an understanding of the histories underlying these practices is important to avoid the pitfalls of cultural appropriation.

Shopping spiritual

The Garden of Light, a Bank Street shop that sells products representing a range of spiritual practices, has coalesced many cultural traditions into a single retail haven.

A staff member and social media co-ordinator said customers were eager to return to the peaceful setting when pandemic safety restrictions eased, especially ahead of the Christmas holidays.

Though the Bank Street location only opened in 2019, the business has operated for more than 21 years. Nérée St. Amand, the store’s founder and owner, said the spirituality scene in Ottawa has grown since the business began.

He was encouraged by the late Indian spiritual leader Sri Chinmoy to begin the business, adopting the name that the author and meditation advocate suggested.

The store’s goal was further informed by St. Amand’s membership in the Parliament of the World’s Religions, a Chicago-based organization that strives to “cultivate harmony among the world’s religious and spiritual communities.” He has traveled throughout the world to support the group’s goal of bridging disparate faith communities.

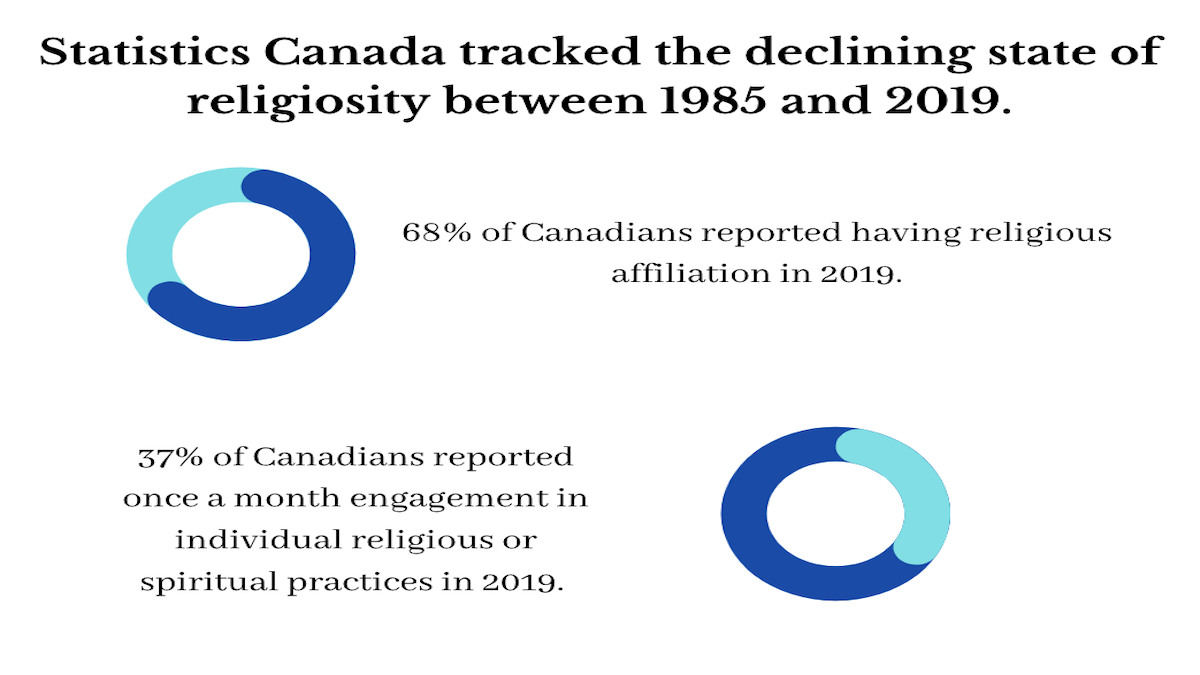

Still, more than one-third of Canadians reported engagement in individual religious or spiritual practices.

Claire Freeman, a first-year communications and humanities student at McMaster University, remembers feeling an unease associated with her Catholic upbringing.

“I always sort of felt excluded,” she said. “There are a lot of rules whereas in spirituality it’s very free.”

Tessa Rollwagen, a third-year English student at Carleton University, also grew up in a Catholic family. She said that while religion was something inherited that fostered little attachment, engagement in spirituality was a conscious choice.

Astrology, tarot, meditation, yoga and the use of healing herbs and crystals are among the multitude of conduits into the spiritual world. Such practices became popularized in the Western world during the 1970s as counterculture movements persisted.

During the pandemic, Freeman said she deepened her knowledge of astrology and tarot. Rollwagen, who also explored those practices, ventured into witchcraft.

Decolonizing Western wellness

In the 21st century, the internet has given rise to what York University PhD student Roland Shainidze calls a “Digital Religion” where online portals make accessibility to diverse belief systems simpler than ever before.

On TikTok, the hashtag #SpiritualTok has more than 1.2 billion views. But social media is not the ideal entry point into spirituality, as its transient nature often flattens spiritual practices into wellness habits rather than encouraging a deeper appreciation of culturally relevant traditions.

Rollwagen conducts her own research. She said finding high-quality spiritual materials is difficult when local metaphysical stores sell appropriated products.

“I think a lot of Western society has whitewashed a lot of other religions and spiritual practices,” she said.

Mavinder Gill, host of the University of Toronto’s Subaltern Speaks podcast, said many spiritual practices have been co-opted by wellness culture and subsequently reinvented to cater to the Western palette. Podcast guest Navdeep (Navi) Kaur Gill, a practitioner of Ayurvedic alternative medicine and meditation, emphasized that the decolonization of wellness is necessary for BIPOC communities to reclaim their ancestral traditions.

“You cannot decolonize without being an ally and doing real work with the Indigenous communities of where you live,” she said.

St. Amand said he hopes that through his business, customers can acknowledge and share in the histories and traditions of their chosen practices.

The cultures represented within the store are evident in the singing bowls originating from Nepal and India, cushions made by Indigenous vendors, and books based on Chinmoy’s many teachings about spirituality.

The store also sells sacred materials including sage, incense and the South American native plant Palo Santo, which are bound to the religious and spiritual communities from which they originate.

“We want to encourage these bases of spirituality that … different cultures have,” said St. Amand, adding that embracing practices like meditation and yoga can enhance peoples lives and lessen burgeoning anxieties of present and post-pandemic life. Rollwagen similarly stated the emotional benefits of spirituality.

“Spirituality is you (learning) tools and you (gaining) the tools to turn complex situations into opportunities of growth and empowerment to work through the heavy emotions you face in your daily life in a healthy, productive way,” she said.