Enter the Ottawa Heart Institute outpatient unit, and the first thing you notice is the smell of hand sanitizer and the shrill beeping of heart monitors. The atmosphere is instantly overwhelming, as harried staff rush past you, assistants bustle down hallways, pushing bulky hospital machinery and dozens of patients lie in beds lined up against the wall.

The only objects in many patients’ line of sight for hours as they await treatment are the pieces of medical equipment parked in front of their beds and the fluorescent-lit ceiling above them.

Since September, however, the normally blank ceiling tiles above 30 beds in the Regional Referral Centre and Day Unit display colourful paintings of landscapes, animals, and tranquil scenes in nature.

Stephanie Colpitts organized the ceiling tile project last year, after she stepped in as quality improvement coordinator at the Heart Institute, covering for a maternity leave.

The idea emerged when Colpitts’ mother-in-law, an artist, became ill and was hospitalized in June 2018. Her family brought several artworks for her to enjoy in her room, but Colpitts wished more could be done about the blank space above her bed.

“She spent so much time looking up at the ceiling,” she recalled. Colpitts remembered her sister-in-law saying, “I wish that there was something for her to look up at.” Four months later, when she was offered the quality improvement job, she took the opportunity to start preliminary work on the ceiling-tile project.

Painting ceiling tiles has been a growing trend in health care for over two decades. In the U.S., a non-profit based in North Carolina called Healing Ceilings arranges for artists to donate their painted ceiling tiles to dozens of cancer treatment centres across the U.S.

Since 2011, many Ontario hospitals, such as the Kingston General Hospital, Brockville General Hospital, Port Perry Hospital, and Sunnybrook Hospital in Toronto have started ceiling-tile initiatives of their own.

Colpitts said she believes that most people have an inherent connection to nature, and scenic paintings in hospitals have a calming effect on patients because of what is called “embodied cognition.” To describe the idea, she gave an example of a painting of the ocean showing waves breaking against the shore.

“Embodied cognition is the idea that you can smell the salt in the air and feel the breeze,” said Colpitts, who now works as a data analyst for the Heart Institute. “Maybe it’s those aspects of being out in nature that calm people. The sights, sounds, and smells are distracting you, taking your imagination somewhere else.”

The Ottawa Heart Institute is collecting patient and staff feedback on the ceiling-tile project. Based on responses from 97 patients to an ongoing survey on the project, about 95 per cent of respondents agreed that installing ceiling-tile artwork in other areas would be beneficial for patients. The goal is to see how the project could expand in the future, and identify areas where more tiles could be painted.

Research shows that art can help patients heal. A landmark study in 1992 by Dr. Roger Ulrich, now a professor emeritus of architecture at Texas A&M University, found that “psychologically appropriate art” can reduce anxiety, lower blood pressure, shorten hospital stays, and reduce the need for pain medication. His study found that open, calm, nature-based scenes in art benefit adult patients the most.

Ottawa artist Bev Legault contributed a tile depicting a rocky pond, reflecting the trees and bridge above it. She had the idea for the painting before she’d heard of the OHI project from a photo she had taken of the bridge. She chose to donate that one because “as an artist, I loved the way it led the person into the painting.”

Legault wanted viewers to lose themselves in her painting, as the typical distractions in hospitals do little to ease nerves. “I find when you do go in doctors’ waiting rooms, normally what you see is a poster. You know, they’re of the digestive system, and cancer. That’s not calming. That’s not good for people who are stressed and worried.”

Legault recalled her own nervousness before a routine medical procedure: “For two hours I stared at a blank wall, getting more and more anxious. (…) Because I was scared, I just couldn’t get into listening or reading, but had there been, say, a nice scenery in front of me, I’m sure that would have given me something to focus on.”

In a 2010 review of case studies in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, colour was found to have a significant effect on patients’ emotions. Researchers concluded that paintings that mostly used blues and greens were proven to lower anxiety and heart rates. That is why the Ottawa Heart Institute specified that the donated pieces show landscapes and nature scenes, since those are dominated by blues and greens and improve patient outcomes.

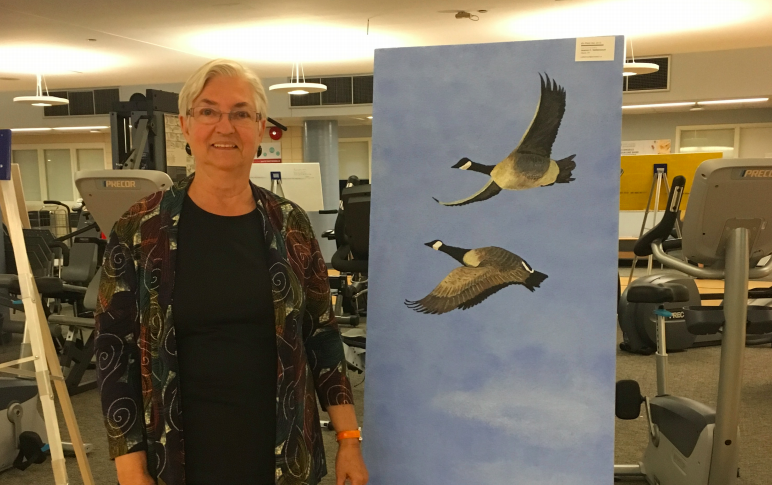

Quebecois artist Jeanne Vaillancourt’s tile showed a painting of two Canada geese, soaring in the sky. She had previous experience painting on ceilings to help a patient, when a friend developed Lou Gehrig’s disease and after a few months became bedridden.

Vaillancourt volunteered to paint a scene above her bed, and each season she changed the scene to match the outdoors. In winter, she painted children playing in the snow, and in spring she drew colourful, blooming flowers. She created four paintings per year, for 12 years, until her friend sadly passed away five years ago.

Vaillancourt said art helps patients going through hard times.

“Art gives you the opportunity to reflect on something else. If you are sick in the hospital and you see the sea or something, your imagination gives you the chance to go out, to be calm and think about something other than the result of your exam. It is for this reason I paint birds. You can fly with the birds outside the hospital; you can imagine you’re in the sky.”

For University of Ottawa student and artist Mimi Deng, she hopes her painted ceiling tile helps patients emotionally by giving them a break from the monotony of a hospital room. “Hospital units often have a cubicle-like quality, with similar layouts and the same instruments at every bedside,” she said.

“Having a piece of art kind of makes that space more unique,” Deng said, adding that “having that on the wall (reminds) the patient that they’re special.”

With the goal of painting 17 plain tiles, the Heart Institute put out a call on social media at the beginning of the summer of 2019, looking for artists to paint calm and open-based nature scenes. After a CBC article on the project ran in June, more than 100 artists applied, and Colpitts was able to expand the project by adding 13 more tiles in the neighbouring inpatient unit.

Part-time artist Emily McCann said she will never forget the experience of painting ceiling tiles.

“It was a really big honour to be a part of something like that,” McCann said. “If I could get another opportunity to do something like that again, I would definitely want to do it.” McCann said she has always wanted to have a positive impact on others, “and through art is the best way I can offer that.”