Canadian journalists gathered recently at Carleton University to discuss the hate and harassment reporters face daily and the efforts in newsrooms to combat online threats.

The in-person and online event, titled “Journalists and Online Hate: What to do when the battlefield is everywhere,” was hosted on Dec. 1 by Carleton’s School of Journalism and Communication in partnership with CBC/Radio-Canada and the Stursberg family, which also sponsors the school’s annual foreign correspondent’s lecture.

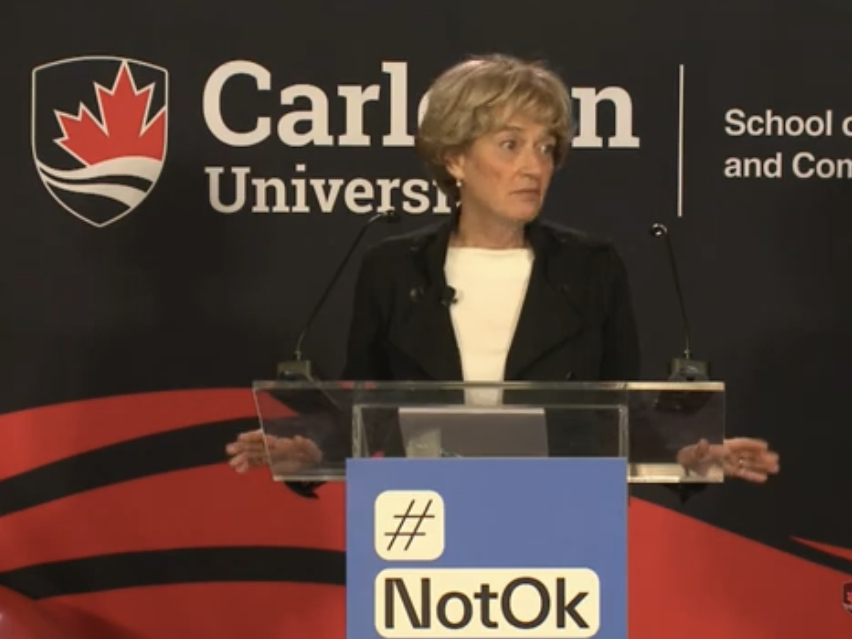

Catherine Tait, president and CEO of CBC/Radio-Canada, said news organizations across Canada that have been forced to address hate and harassment on social media directed at reporters, are adapting many of the practices employed when sending journalists into conflict zones.

“For journalists today, the battlefield is everywhere,” said Tait, pointing to preliminary findings from a CBC study conducted with Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre that indicate reporters are paying an emotional toll for being on these platforms.

‘Every day in my job right now, as editor-in-chief of Global News, I see incredibly violent messages that are forwarded to me by (reporters).’

— Sonia Verma, editor-in-chief, Global News

The study, which Tait said will be released next year, found that journalists dealing with forms of online violence are more likely to experience significant symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety and depression.

Sonia Verma, the editor in chief of Global News, echoed Tait’s remarks and recounted her own experience reporting in Egypt in the days leading up to then-president Hosni Mubarak’s resignation during the Arab Spring uprising of 2011.

“I know what it feels like to feel really scared and feel like you’re under attack,” said Verma, recounting an incident when a group of men, unhappy with western news coverage of the growing unrest, marched up to her and a colleague in an interaction that quickly turned physical.

Verma described how she felt “totally overwhelmed and powerless.”

“Every day in my job right now, as editor-in-chief of Global News, I see incredibly violent messages that are forwarded to me by (reporters),” said Verma, drawing parallels between the anxiety she felt in Egypt and the experiences of reporters on her staff, calling the online violence “just as serious (but) more insidious and more difficult to deal with.”

Tait and Verma outlined steps being taken by their newsrooms to protect reporters, including disabling the comment section under articles and implementing an email filtering system that keeps violent messages from reaching reporters.

Joining the panelists was federal Public Safety Minister Marco Mendicino, who said online threats against journalists were “obviously criminal conduct” and that “it is racist, it is misogynistic, it is criminal, it is against the law and it is intentional that it targets disproportionately women.”

Still, some of the reporters on the panel weren’t convinced that authorities have fully grasped the intersectional extent of such threats and doubt that existing measures to combat the scourge are enough to effect any significant change.

Global News reporter Rachel Gilmore pointed to law enforcement’s continued failure to address credible threats to journalists’ safety and shared details about how she had reported receiving a video of a man wielding a knife and making threats only to be told that it “did not constitute a threat under the Criminal Code.”

‘Reporters cannot simply disengage from these platforms, in an increasingly digitized world, that helps connect to communities.’

— Saba Eitizaz, reporter, Toronto Star

Toronto Star reporter Saba Eitizaz and Hill Times columnist Erica Ifill said suggestions to leave platforms are naïve and not viable for many of the reporters facing the bulk of threats and violent messaging.

“Reporters cannot simply disengage from these platforms, in an increasingly digitized world, that helps connect to communities,” said Eitizaz, adding that leaving social media platforms is rarely enough. Even after disengaging and only logging in to promote her work, Eitizaz said she continued to receive threats.

For Eitizaz, who came to Canada after being hounded out of her home country of Pakistan because of her reporting, working in a hostile environment in a country that was supposed to be safe was not something she had expected.

“Safe has become an alien word to me,” she said. “I don’t remember what safety feels or looks like. … Ironic, because safe is why I came here.”