“As inconvenient as it is for them, it’s going to be hell for me.”

John Woodhouse lives in Ottawa and uses an electric wheelchair to navigate the streets. The chairperson of Walk Ottawa and advocate for the physically impaired finds it increasingly difficult to travel on unplowed snow-covered sidewalks. The city, he says, is slow to respond.

Woodhouse is not alone. Many local residents and advocates in Ottawa are highlighting the lack of road maintenance on behalf of the city in the winter, specifically on sidewalks.

For Kathleen Fortin, who has been living in Ottawa since the early 1980s, having no help from the city makes her feel like “a second-class citizen.” She, like Woodhouse, uses an electric wheelchair.

“When you’re physically challenged it makes it harder to go out to doctor appointments or to get groceries,” says Fortin. “Being disabled, it’s very difficult to go out during bad weather. I’m not just talking about myself, but I’m also talking about mothers with children and strollers, people with walkers.”

One year, Fortin says, he had to travel on the main road because the sidewalk was unplowed. Fortunately a neighbour was able to assist.

“If it wasn’t for that person, what do you think would have happened?” asks Fortin. “If no one comes along to help you, you could be stranded for a couple of hours, and when the weather is really [cold] … you could freeze to death.”

Stephen St. Denis has always lived in Ottawa. So he knows the challenges of getting around this city very well. He uses an electric chair and has had similar experiences. Last February, for example, his chair got caught on a patch of ice and snow and flipped. In April, he became stuck in cold mud on the way home from church on a path in Ruth Wildgen Park. A puddle enveloped his front wheels and he was unable to move.

A stranger tried to help, but the chair was too heavy. At this point, the icy water was leaking into St. Denis’ shoes, so he dialed 911. Firefighters, a police officer, and paramedics arrived to free him.

“I think a big problem is that there is a lack of co-ordination,” says St. Denis, who filed a complaint to Bay Ward Coun. Theresa Kavanagh. Eventually, he says, he spoke to Kevin Wylie, general manager of Public Works and Environmental Service, who agreed the whole area should be resurfaced for proper drainage.

“Well the update is, there is no update,” St. Denis says. “Absolutely nothing has been done. It’s unbelievable.”

The City of Ottawa website says snow clearing will occur on sidewalks within 16 hours “after the last snowflake falls,” and for bus stops, within 24 hours. City infrastructure also falls under the Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act (AODA).

“One thing is indisputable, this path [in Ruth Wildgen Park] is not AODA compliant if I have to call 911 to use it,” says St. Denis. “When they don’t conform to the standards, then the appropriate action must be taken. The city should sit down with that operator or contractor and explain that it does not meet the standards. And if that worker has to be retrained, well … retrain them.”

Similarly, Kyle Humphrey, the founder of the local group No Such Thing As Can’t, says the city is slow to respond to the needs of those with mobility issues, including ParaTranspo services.

“In my neighborhood [Orleans], because I’ve called the city 1,000 times, they’ll clear the bus stops,” says Humphrey. “But if I want to go across the city, and the bus stop isn’t cleared, I have to essentially get off in the middle of the road.”

Humphrey says he is critical of the city prioritizing the new LRT system over the needs of those with mobility issues in the winter.

“We’ve been trying to tell them for a long time. The unfortunate part is that you can’t tell someone something that they don’t want to hear,” says Humphrey. “I think it’s really important for them to understand that people are trying to live their lives, just like anyone who is using the LRT is. For them to neglect clearing the sidewalks … it takes away people’s ability to get out.”

Trevor Hache works at the Healthy Transportation Coalition in Ottawa, which connects 35 local advocacy groups. Hache says current city standards are inadequate and that the public should voice their concerns to the mayor.

“If he were required to walk more often on the city sidewalks in the wintertime, maybe he’d have a greater appreciation for the challenges that his policies are creating for people,” says Hache. “It really limits people’s ability to live a full and rich life, and in some cases, it limits their ability to just be healthy.”

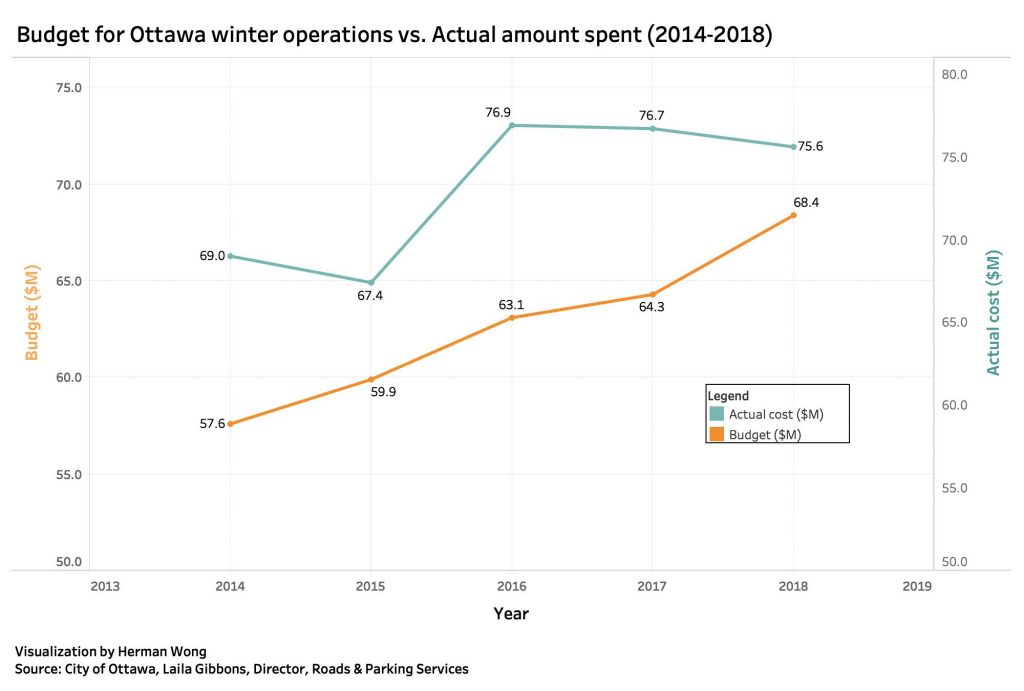

The proposed 2020 city budget has allotted $78.3 million for next year’s winter operations, which includes snow removal, a $5.6 million increase from the previous year. However, for several years, the actual amount spent on winter operations has been over budget, based on official records provided by the city.

“I hope that it’s better this year than it was last year because last year was terrible,” says Sally Thomas, a local accessibility advocate. Living in Manor Park, she is unable to go on sidewalks with more than two centimetres of snow with her manual wheelchair. As a result, Thomas says she feels “confined” to ParaTranspo.

“No one I’ve talked in a position to do something seems to understand the gravity of not clearing the snow,” says Thomas. “If they’re not noticing, obviously it’s not going to change.”

Thomas started using the hashtag #OurOttawaIncludesUs as a way to encourage other local residents to advocate for the inclusion of marginalized communities. On social media, she says, city councillors are active and may produce immediate reactions. Moreover, she says it is important to start the conversation and keep it going, including writing to city councillors.

“It’s 2019. I shouldn’t have to ask to be able to leave my house. I shouldn’t need to beg for certain things that I’ve had to beg for,” she says. “The city needs to accommodate us.”

Rideau-Rockcliffe city councillor Rawlson King says that “Sally Thomas is right.”

“The problem is when you call staff, often there’s that challenge of waiting. It’s kind of frustrating with a customer service kind of scenario,” says King. “I think the people are correct. There are gaps in the way that services are delivered, especially for people with disabilities. The key is working on it in a holistic way.”

King says the city is making sidewalk clearance a priority this season, with quality maintenance standards to be reviewed next year.

“The quality standards [for snow removal] have not been reviewed in a number of years,” says King. “Once they’re reviewed, there’ll be public input over the next year, and there will be definite changes.”

An advocate in transit commission meetings as well, King says that the city should listen to people’s concerns for the sake of “parity.”

“We have to get to a point where systems are reliable … so that persons with disabilities have access to quality transportation and be treated in a way with their public services that is dignified,” says King. “That’s what’s really important, to ensure that people’s human rights are respected, that their capacity to get to places is not a challenge, and the way they interact with public services isn’t an everyday battle.”

This is a goal that Terrie Meehan, vice-president of the Healthy Transportation Coalition, would love to see realized.

Meehan says that keeping the city accountable is important and is something she does through her advocacy. To have parity, she says that the city’s “we’ll get to it when we’ll get to it” attitude must change.

For emergency requests concerning road or sidewalk maintenance, you can call 311 or 613-580-2400 when the service is unavailable. Other comments or suggestions about sidewalks can be submitted to the city here. For road maintenance, comments can be filed here.