When she was 10 years old, Angela Alves learned Calabrese, a regional language in Italy, to be able to communicate with her grandmother. Five years after her grandmother’s death, Alves continues to practice the language with her relatives at least once a month.

She tried to learn standard Italian in university, but says she prefers to speak Calabrese. “I find it more emotional. Maybe that’s because of my personal connection to it, but I find that it’s more of an emotional language,” she says.

Each audio clips shows the difference in the dialect from various regions. The phrase “Let’s go, kid” is first translated into standardized Italian and then into the subject’s dialect.

In Italy, there can be some stigma attached to regional and minority dialects such as Calabrese. These dialects are dying out with older generations, but for many first- and second-generation Italian Canadians, these languages are surviving through generations.

Alves says she hears Calabrese spoken in stores, churches, malls, nursing homes and hospitals in Ottawa. “You hear it from time to time, but it’s almost like a hidden language because there’s not many people that know it. Even though there are Italians around.”

Alves says she hopes to keep the family’s language alive now that her brother’s children are starting to reach the age she learned Calabrese. “I think it’s important to understand the culture and the background you have, understand your roots, and continue to pass it through your bloodline. Even though, we’re in Canada and we’re very much Canadian and proud for it, we’re still very proud of our ancestors and the roots that we have.”

Paul Rausch, who writes for the website Cadèmia Siciliana (Academy Sicilian), says for his parents’ generation, regional and minority languages were associated with criminality, with less education and with poverty, but today younger generations want to learn the language to connect to their cultural roots.

“For them it’s associated with their grandparents, with home.”

Growing up in the U.S., Rausch said he never heard Sicilian spoken outside of his family home. He noticed his Canadian relatives had a much higher language transmission rate than his family living in the U.S. He wanted to hear the embrace of regional and minority languages for himself. While visiting Ottawa, Rausch said he was brought to tears hearing Sicilian in a café.

“It was a big shock to realize that in Canada there was much higher language transmission rates,” he says.

According to a 2011 analysis from Statistics Canada, U.S. language transmission rates are lower among immigrants who favour of teaching their children English. In Canada, immigrants struggle to hold onto their original language, but they have a more “balanced outcome” in passing along the language to future generations.

Rausch founded Cadèmia Siciliana to help preserve the Sicilian which is based in the south of Italy. Rausch is also an advocate for all minority and regional languages in Italy, hoping to help younger generations continue their grandparents’ language.

He explained that in Italy there are five regions that feature certain dialects. These are: Northern Italy, Tuscany, Sardinia, Central and Southern Italy. These dialects can even vary from town to town. Some are what Rausch calls “sister languages” to standard Italian. Others can function like a national language and can be entirely different from standardized Italian.

The map shows the various towns from where the ancestors of Angela Alves, Carmela Parent and Nadia Telford come. The highlighted area shows the region of Tuscany. Today, the Tuscan dialect is now the national language of Italy.

Rausch compares the lack of recognition of regional and minority languages in Italy, both legally and formally, to the situation gacing Indigenous languages in Canada.

He says the belief that these languages are dying out is not accurate. “Most of our membership, most of our volunteers … are not the stereotypical image of old people,” he explains. “We’re using it online, we’re using it in the 21st century.”

But passing along the language can be difficult. Carmela Parent says she hopes to pass along standardized Italian to her children. As for passing along her minority language, she says it’s difficult because she is the only one in the family able to teach and practice the language with her children.

“I think it’s really unique being that Italy is such a small country with so many various dialects versus Canada that is so huge and English is pretty much standard,” says Parent. She is the only one in her family not born in Valluce, a small town near Cassino in Central Italy, but she still continues to speak the local dialect called Ciociaria. While her sister and mother still live in Windsor, Ont., Parent, a 46-year old retired sign-language interpreter, speaks to them on a weekly basis weekly on the phone in their dialect

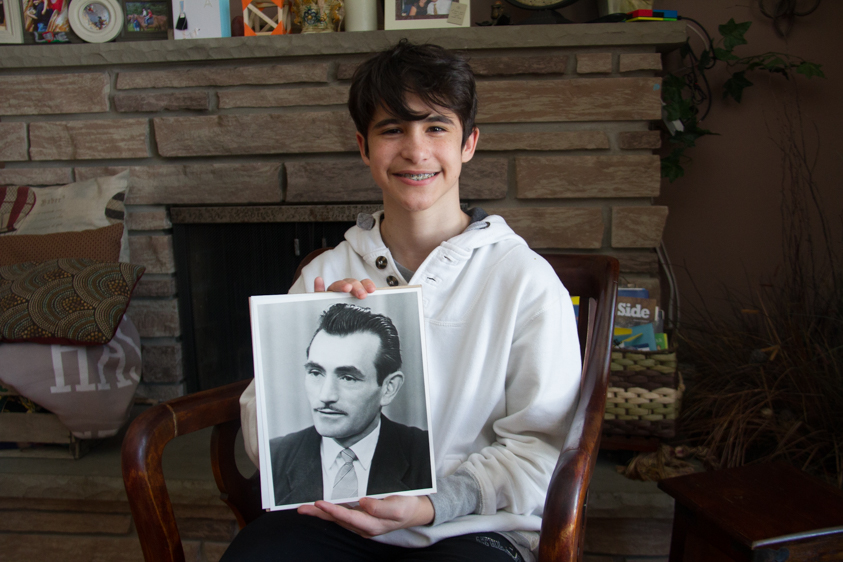

Parent’s 12-year-old son says he understands some of the standardized Italian, but none of their family’s dialect. “It’s so hard [to learn]. [My grandmother] can barely understand me because she speaks more Italian than English. I would like to, but I don’t really think I can,” Robert Parent says.

Parent often jokes that she and her sister have created their own dialect – a mix between English and Ciociaria. “We make an English word into Italian,” she said. Parent and her sister often combine English nouns and add Italian definite articles (like ‘the’ in English), to make a word sound Italian.

Findlay Creek resident Nadia Telford says she was worried when she visited Italy last year that no one would be able to understand her. She never spoke standardized Italian growing up, instead learning her family’s town language, Abruzzese – a language from the region of Abruzzo in central Italy. She says she was surprised when a local shopkeeper in Naples could pinpoint the region her family came from.

For Telford, the language is a cultural identifier. She continues to practice it daily with her grandparents, who live near her. She says she always assumed she was speaking standard Italian until she was a teenager.

“It’s just very unique to each region and I find that it’s very beautiful to be able to pinpoint where it’s from and to know that it came from them and everyone before them,” says Telford, who is a 27-year-old first-generation Canadian.