Only two acres of a 160-acre site was searched by ground penetrating radar, said the scientist who found the unmarked graves of at least 200 Indigenous children who attended the former Kamloops Indian Residential School in British Columbia.

Sarah Beaulieu, who conducted the search, said only excavation can definitively tell the exact number of children buried near the school. Her statement was part of a press conference during which the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation released its report on the search of the Kamloops residential school grounds.

The report and search confirmed the likely presence of at least 200 gravesites in an orchard at the site of the residential school, pointing to the need for an extensive search of the entire site to confirm what Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc kukpi7 (chief) Rosanne Casimir said survivors always knew.

“This is heavy truth,” Casimir said.

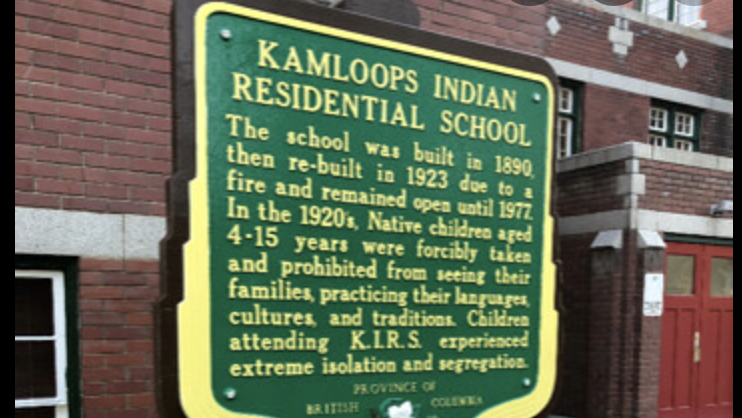

In May, the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation announced the discovery of 215 children buried in unmarked graves on the grounds of the Kamloops Indian Residential School, which operated as a residential school until 1969 and as a day school until 1978.

“This is heavy truth.”

Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc kukpi7 (chief) Rosanne Casimir

Several other communities, including the Cowessess First Nation in Saskatchewan and members of the Penelakut Tribe in B.C., have also announced the discovery of hundreds of unmarked burials on residential school grounds.

The Kamloops search was initiated after a child’s tooth and rib bone were discovered at the site, as well as information from survivors and elders who have long pointed to the fact that children died and went missing at residential schools for decades.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Missing Children Project has found that at least 4,000 children have died at the over 130 residential schools that operated in Canada, although the exact number could be much higher.

Survivor Evelyn Camille, who attended the Kamloops Indian Residential School for 10 years, said she tried to write to her parents about the abuses she was experiencing at the school, but her letters were censored.

Camille said the schools tried to erase the identity of Indigenous children and make them ashamed for who they are. “It did not work, as our culture, language, and way of life are still with us,” she said.

She said years later, her children asked her why she didn’t tell them what happened to her at the school. “I couldn’t share my sorrows with them,” she said.

Casimir urged the federal government to release the attendance records required to identify the children who died at the school to aid in the community’s investigation into identifying the children.

“Those documents will be of critical importance to identify those lost children,” she said.