It’s 4 a.m. The sky is still speckled with stars and ice is glinting in the streetlights from the freezing rain.

You can hear the hiss and groans of large trucks shooting out bullets of road salt, a sound that, to you, means a safe drive into work. But for the species living in nearby waterways, it is the sound of an assault on their habitat by another round of poisonous pellets that kill their young and threatens the ecosystems upon which they depend.

Since the 1950s, Canada has used road salt as a cheap and effective way to break up ice and keep citizens safe during the winter. More than seven million tonnes of road salt are spread each winter, according to the World Wildlife Fund.

Some waterways in Southern Ontario have now eight times the recommended level of salt, surpassing more than 1,000 milligrams of salt per litre, the WWF found in a 2019 report.

Now the Ottawa Riverkeeper is raising the alarm about the impact of road salt on waterways in the National Capital Region.

Startling new findings from a pilot testing by the non-profit organization found waterways with more than 800 milligrams of salt per litre – seven times the healthy level. One creek showed sky-high readings of 3,500 milligrams per litre in mid-February, according to data released March 16.

Monitoring the waterways

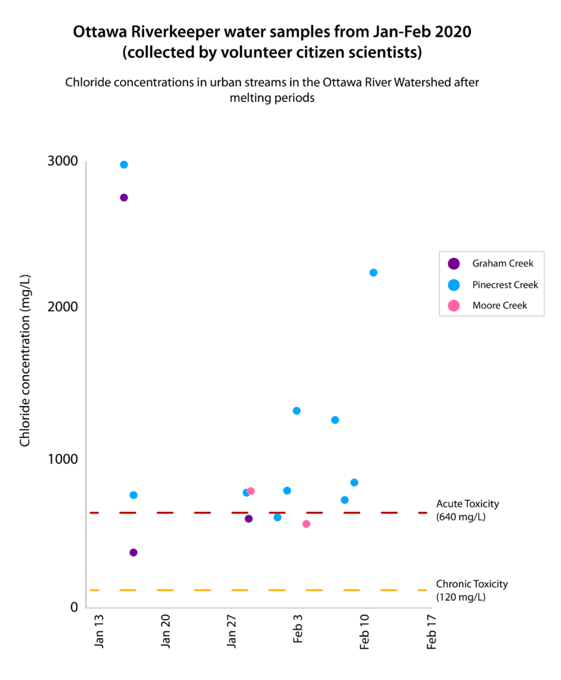

These tests are part of a monitoring program that started in mid-January. It consists of weekly tests on local waterways to determine salt concentrations during the winter months. The Ottawa Riverkeeper is monitoring Pinecrest Creek, Graham Creek and Gatineau’s Moore Creek, as they all feed into the Ottawa River.

Aquatic organisms can survive in freshwater if salt levels are kept below a constant threshold of 120 milligrams per litre, the Riverkeeper’s first report noted on March 7. However, the newest data shows that all the creeks being monitored surpassed this threshold this winter, some by an alarming amount.

Pinecrest Creek, for example, consistently contained salt levels of about 800 milligrams or higher, spiking to 3,500 milligrams per litre in mid-February, and salt levels in Graham Creek exceeded 1,500 milligrams per litre twice this winter, the data shows.

“I was just surprised. I thought, ‘What more can we do? How can we get this message through to people?’” Elizabeth Logue said. The Riverkeeper added that there are plans to expand the program to gather data from more local creeks.

Every winter, 190,000 tonnes of road salt is used by the City of Ottawa, the city’s operational research and projects manager, Kevin Monette, said in an email. These amounts do not include the road salt dispersed by private contractors or individual property owners. The city hasn’t updated its salt management plan since 2005, although it conducted a general study of surface water quality in 2017.

Though the City of Ottawa says it is committed to testing waterways on a monthly basis, the testing is only done “in non-ice conditions,” because of safety concerns, Ryan Polkinghorne, the city’s environmental monitoring manager, told CBC on Feb. 1. The Riverkeeper launched its new monitoring program partly to ensure that data is collected throughout the winter, when road salt is most heavily used.

As road salt — in the form of sodium chloride, calcium chloride or magnesium chloride — makes its way to nearby waterways, Logue said it threatens ecosystems and wildlife. Excessive amounts of chloride degrades habitat quality, along with increasing egg mortalities and decreasing the biodiversity that keeps our freshwaters healthy.

“Especially with amphibians that breathe through their skin, they are getting this chloride directly into their system,” she said, explaining that salt tends to draw moisture out of their skin and dehydrate them. “The levels are high enough to affect their health and whether they are able to survive into the summer.”

A 2016 study by researchers at Yale University and the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute also found that excess salt concentrations can increase the number of male frogs, while decreasing the number of females by 10 per cent, affecting the number of offspring and future populations. This likely happens because sodium binds to cells and mimics testosterone, the study explained. As a result, not only are there fewer females, but salt also lowers the number of eggs that females can produce.

Species suffer

And it’s not just frogs that are affected. Many other species with low salt tolerances are unable to procreate or have a higher rate of egg mortality, Logue explained. For example, high concentrations of salt affect the appetite of dragonflies, which then makes mosquitoes more plentiful in the summer, she said.

In Ottawa specifically, the hickory nut mussel, which was added to Ontario’s species-at-risk list in August 2019, may face even more challenges with increasing salt levels. Historically abundant in the Ottawa River, these mussels play an important role in filtering our waterways, Logue said.

Chloride levels hurt even the tiniest specimens, according to Robin Valleau, a PhD candidate in biology at Queen’s University. Her work is focused on the Muskoka region, where she is studying how salt levels affect zooplankton in freshwater systems—important species at the bottom of the food web.

“(Zooplankton) filter the algae out of the water, which makes our lakes clear and esthetically pleasing, and they are also a main source of food for some fish,” she explained.

Increased salt levels in the water have introduced more salt-tolerant zooplankton, which can be harmful for fish that are used to eating other kinds of zooplankton. This has led to a decline in the number of fish in lakes with higher salt concentrations, she said.

These studies provide valuable information about the risks of road salt to larger waterway systems, such as the Great Lakes, she added.

“We have these early warning signs in our shallower systems that are more sensitive to changes, and a lot of our big, productive lakes like the Great Lakes haven’t reached chloride levels that are of concern,” she said. “We’re catching it early enough that we could do something. And really, the biggest solution is using less salt.”

Humans should also be concerned about the increase in salt concentrations in local waterways because it pollutes drinking water and damages the beloved freshwater systems so integral to Canadian identity, experts say.

“Some people don’t realize that our drinking water does come from the Ottawa River,” Logue said, noting that once salt is in the water, it is hard to extract it. “Salt doesn’t just disappear into thin air … I guess people don’t see that full-circle effect.”

Although road salt isn’t an acute threat to ecosystems on the level of climate change and habitat loss, Nick Lapointe, a senior conservation biologist for the Canadian Wildlife Federation, said the steady accumulation of salt over time is concerning. He agreed there is no easy way to take salt out of freshwater.

Not sustainable

“The way we use road salt is just not sustainable. It’s not something that future generations are going to be able to deal with,” he said. “We’re currently on pace within the next couple of decades — 50 to 100 years — to have this become a big problem in our urbanized watersheds.”

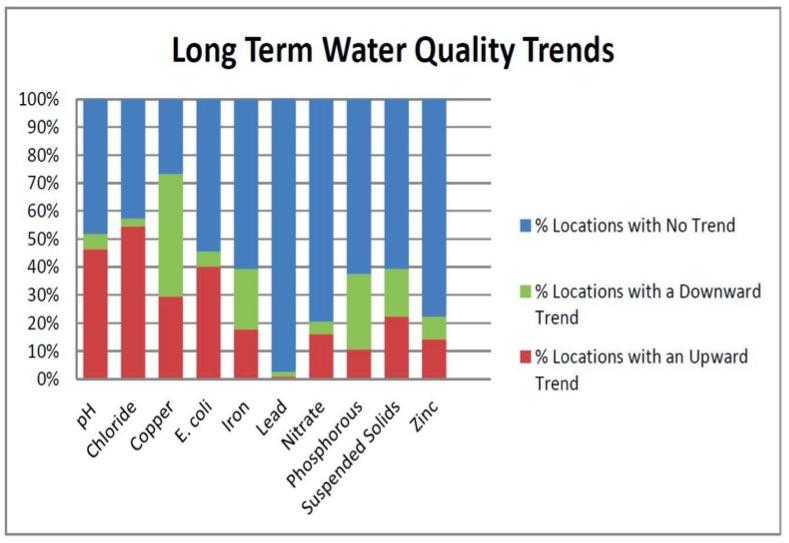

In 2017, city staff prepared a Surface Water Quality Report for council’s climate protection committee. This report found that, although overall water quality had improved between 2000 and 2014, with a decrease in levels of substances such as copper and phosphorous, chloride levels had risen in local waterways.

“Although chloride may be naturally occurring, there is evidence to suggest the source of the city-wide upward trend for chlorides is an increasing release from road-grade salt from both public roads and private commercial properties,” the report stated, although it did not explain the reason for this increase.

to highlight the increase in chloride levels between 2000 and 2014. [Courtesy the City of Ottawa]

Ottawa has been trying to manage its use of salt for years. In 2005, the city developed a detailed salt management plan outlining practices the city could take to reduce the use of road salt.

For example, lightly spreading “liquid de-icers” such as sodium chloride brine over road salt effectively accelerates the ice-melting process by “pre-wetting” the salt. In turn, this reduces the amount of salt needed, the plan stated.

Acknowledging this plan, Logue said it’s good the city trains the staff on salt management practices, but “given that we still see high levels in creeks, it makes us wonder if this is enough.”

For more than a decade, the city has continued to invest heavily in liquid de-icers, along with computer controllers in all salt spreaders to accurately control the amount of salt used, Monette said in an email. The city also often uses sand on lower-priority roads, according to Coun. Scott Moffatt, who is also the chairman of the standing committee on environmental protection, water and waste management.

However, the province requires cities to meet minimum road-maintenance standards, which can influence the amount of road salt dispersed. These standards include having bare pavement on main roads such as Carling Avenue and Baseline Road. Keeping sidewalks ice-free also increases public safety and ensures the city doesn’t face lawsuits.

“If we don’t maintain these things and we don’t manage the ice, then we’re liable in case there’s accidents or in case someone falls,” Moffatt said. “That comes back onto the city.”

Best practices

When asked whether the city has succeeded in reducing salt use since the report was published, Monette said in an email that the city has been following best practices to maintain its salt usage to the “minimum required to achieve public safety.”

Ottawa has also looked into using alternatives to road salt. In 2011, the city tried to use a beet juice solution, but it was deemed ineffective, according to Monette. No significant benefit was observed compared to the liquid de-icers the city was already using, and there were issues with foul odours and staining, he explained.

Though alternatives such as beet juice have been introduced in various cities, including Winnipeg, Chicago and, most recently, Cornwall, Valleau said she doesn’t think they are the best solution, as they may have negative consequences that haven’t yet been identified.

“Not a lot of research has been done on these alternatives because they are so new,” she said, adding that using less salt is always best. “I would caution people when using new products because we don’t know how they will affect lakes.”

Another way Ottawa has addressed concerns about rising salt levels is having participated in Smart About Salt’s training program, the 2017 Surface Water Quality Report said.

The organization aims to train contractors and municipalities across Canada to improve their road salt practices, giving them a certificate in the process. Applying best practices, such as using liquid de-icers, can “reduce the use of salt by as much as 70 per cent, while maintaining safety and saving money,” according to executive director Lee Gould.

Though the city was involved in the program in 2011, Monette said Ottawa is not currently participating, but did not explain why in his email statement.

Meanwhile, homeowners and entrepreneurs can do their bit, Logue said. An example of a best practice for homeowners, according to Logue, includes reducing the amount of road salt used on sidewalks and driveways.

“I’ve seen it where there is more salt than snow in some areas,” she explained. “For a driveway, you don’t need several shovel-fulls. You just need a coffee cup-full—that’s what we’ve been trying to educate people about.”

Limit usage

Elizabeth Hendriks, the vice-president of freshwater for World Wildlife Fund Canada, recommends using one pill bottle’s worth of salt per square metre.

Though road salt trucks disperse most of the salt that washes into our waterways, she said most people would cut back on their own use of salt on sidewalks and driveways if they knew about its impact on the environment.

“It is an actionable issue,” Hendriks said. “Sometimes we have these environmental issues that people think are too overwhelming, but saying, ‘Let’s reduce our salt and it will have a positive impact on our freshwater ecosystems,’ interests people.”

Canada has the highest number of lakes in the world – a fact that gives people an extra incentive to protect them and ensure our freshwater ecosystems can continue to thrive, she added.

“Canadians really care about our freshwater. It is part of our identity and when we become aware of the impacts we are having, people do care and want to change.”

Chlorides cannot exist alone. It is CL-, remember your high-school chemistry. They need something to attach to, to get the extra electron. What they attach to is just about anything heavy. So metals. They cause corrosion. That corrosion destroys everything. Luckily for us, lead levels are very low, otherwise Lead Chloride would be everywhere and we would be dead. As it is, even minute lead in our water is unhealthy

Salt also corrodes concrete and the re-enforcing bars in in. All this salt use has probably done a pretty good number on city sewers.

Please write your councillor. I did.

excellent article