Tina Ford knows first-hand the struggles to pay rent in Ottawa. The student and housing activist has lived in subsidized housing in the city for years and says the current state of affordable housing in Ottawa is seeing people pushed onto the streets or into crowded shelters because of affordability issues.

But, as bad as it is now, she fears the price problem will get much worse thanks to the next phase of the city’s LRT plans.

Phase 2 of Ottawa’s LRT is expected to create $4.5 billion in economic benefits when trains start running through stations. But activists and urban planners say re-development from the project risks cutting down on the supply of affordable housing as neighbourhoods near rapid transit become more expensive. Unless the city finds a solution they say, the city’s poorest residents will be priced out across much of the city.

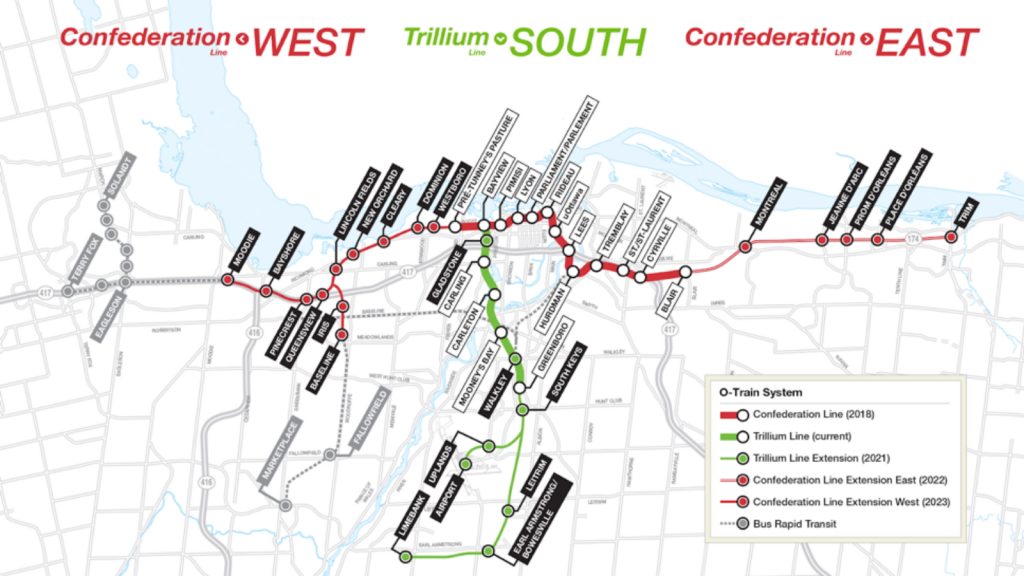

The $4.7-billion project will expand light rail east to Orleans, west to Moodie Drive and south to the airport. It is scheduled to open in sections between 2022 and 2025.

Map depicts LRT Phase 2 plans, with new stations highlighted in black. [City of Ottawa]

“We’re worried that the land around it will become more valuable,” said Ford, a member of the anti-poverty group ACORN, “and so you’ll see more poor people not being able to afford the rent there.”

“There’s a lot of people that are not housed, or waiting for housing, or living on people’s couches or in shelters,” Ford said. “Even though they’re the people who need transit the most, it’s not going to serve them,” she added.”

ACORN is demanding 25 per cent of all new development near light rail be designated for below market rent.

Experts say their concern is legitimate. Steve Pomeroy, an Ottawa urban planner and housing policy consultant, said new rental properties coming on the market this year are going for 65 per cent more than the median rent, which is already far out of reach for many lower-income households.

“It’s incumbent on the city to get ahead of these issues. I think it has probably missed the train, so to speak, on the first phase, but we still have a chance on the second or third phase,” Pomeroy said.

The issue is not just about new properties either. Existing low-rise properties near light rail risk demolition to make way for more expensive high-rise replacements.

The city recently announced a boost in funding for new affordable housing in response to such concerns, budgeting $15 million this year. Activists had initially demanded $12 million. The city has also recently identified five municipal properties near the LRT for city-run community housing.

But experts say that the underlying issue the city needs to address is a lack of affordable housing built by developers and inadequate zoning laws.

Pomeroy suggested one way that the city could meet ACORN’s 25 per cent demand is by requiring a portion of all new developments to be affordable, a technique known as inclusionary zoning. Pomeroy said the percentage of affordable housing the city can reasonably ask from developers depends on how far below market rent the city demands. The farther below market the city asks for, the greater the cost to developers.

Developers tend to bid and buy up land at a significant premium many years before stations even open, with the expectation of recouping the higher purchase price with pricier high-end developments, said Pomeroy. Such developers would see the value of that land decline significantly if the city suddenly required them to build affordable housing instead.

“Unless the city pre-zones and sends those signals to the land market ahead of time, then what tends to happen is the developers have already bought up all that land with the anticipation that the city will re-zone without any conditions,” Pomeroy said. When the city does try to put conditions on it afterwards, he said, the developers push back and say that is not fair.

Mayor Jim Watson nonetheless campaigned on introducing inclusionary zoning in the 2018 election last year and said it would be one of his “first priorities” if re-elected. He did not specify what percentage requirement he would like to see.

Rideau-Vanier Coun. Mathieu Fleury, who chairs the board of Ottawa Community Housing, said the city is currently reviewing its options under new provincial law. Regulations introduced last year appear to give the city a wide latitude in designing its inclusionary zoning policies, much more than previous regulations, which did not allow for inclusionary zoning at all.

“We can all envision more affordable housing in new developments that are private,” Fleury said, “but unless the province gives us those tools, there’s nothing we can do.”

Despite the provincial restrictions, there are some proactive measures the city can take.

Fleury said the city has identified 17 additional properties near Phase 2 for affordable development.

Pomeroy also suggested that in addition to building housing on property the city already owns, the city should consider “land-banking,” by buying up land near Phase 2 and Phase 3 LRT stations long before the stations open. This would allow the city to build without using zoning requirements.

Brian Casagrande, a partner at Fotenn, an Ottawa-based urban planning firm, said that now is a great time to work on these affordability issues.

“In my view, the timing is opportune, particularly with the Phase 2 line being planned and implemented,” he said.

“With these lines being drawn, the development community is responding because that’s where the increased demand is,” Casagrande said. “So as that development is coming forward, as that appetite is there, the city has the unique opportunity to work with those developers to create incentives to allow them to provide for affordable housing.”

Aside from inclusionary zoning, there are some proactive measures the city can take.

Kari Glynes Elliott, co-founder of Ottawa Transit Riders, said that while she’s concerned about affordability, she is more concerned about maintaining bus service away from stations, particularly in areas that are already low-income, such as Vanier.

“If they’re planning on cutting bus service and forcing everyone onto LRT, that means worse bus service for us,” Elliott said. “But if they’re planning on taking the savings from LRT and investing it into bus service, we would be much happier.”

Christopher Stoney, an associate professor of urban planning at Carleton University, said neighbourhoods should also expect more traffic near the station from buses, although overall city-wide traffic will be reduced. The city says LRT will take 14,000 cars off the road during rush hour.

Stoney also noted that there are tax benefits to allowing developments with less affordable housing to be built, as the more expensive projects ultimately pay more in property taxes and development fees.

“One of the constant arguments is whether part of the money that is made just from re-zoning should be earmarked for affordable housing,” he said.

All three planners agree that re-development carries many benefits, notably by improving connectivity and by providing an economic boost and better retail service.

“It’s not just about residential development,” Pomeroy said. “It’s mixed-use, so you’re introducing commercial uses as well. You want to create growth hubs around your transit system. You’re trying to create employment opportunities as well as residential opportunities,” he said.

But for Ford the issue is about equality for those who need it most.

“Politicians, developers, OC Transpo and everyone involved in this light rail operation need to know the targets that they need to serve so that they can serve everyone,” she said, “and not just wealthy people.”

[…] Tina Ford knows first-hand the struggles to pay rent in Ottawa. The student and housing activist has… […]