The University of Ottawa has launched Canada’s first academic research centre dedicated to health in Black communities.

The Interdisciplinary Centre for Black Health will examine the biological, social, cultural and economic determinants of Black health. With researchers from several disciplines, such as medicine, law, sociology and nursing, the aim is to promote health equity for members of Black communities across Canada.

Led by Dr. Jude Mary Cénat, associate professor in the Faculty of Social Sciences, one of the centre’s goals is to promote community engagement through discussion forums. “The centre must build real trust with Black communities. We have to do things with them, not for them,” said Cénat.

In a 2019 study conducted by Cénat and colleagues, it was found that more than 53 per cent of BIPOC Canadians say they have experienced racism when interacting with health care services.

“Racial discrimination plays an extremely important role in depression among members of the Black community,” said Cénat. “Those who experience a high level of racial discrimination are 36 times more likely to experience symptoms of severe depression compared to those who experience less racial discrimination.”

The ICBH was originally going to focus on mental health, but was broadened to cover general health overall with the support of Vicky Barham, uOttawa’s dean of the Faculty of Social Sciences.

The centre “is a pioneer of its kind, and its interdisciplinary vision will ensure its success. It will not be long before we see the benefits for the wider community,” she said.

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the disproportionate impact of health risks on racialized populations in Canada, the U.S. and elsewhere.

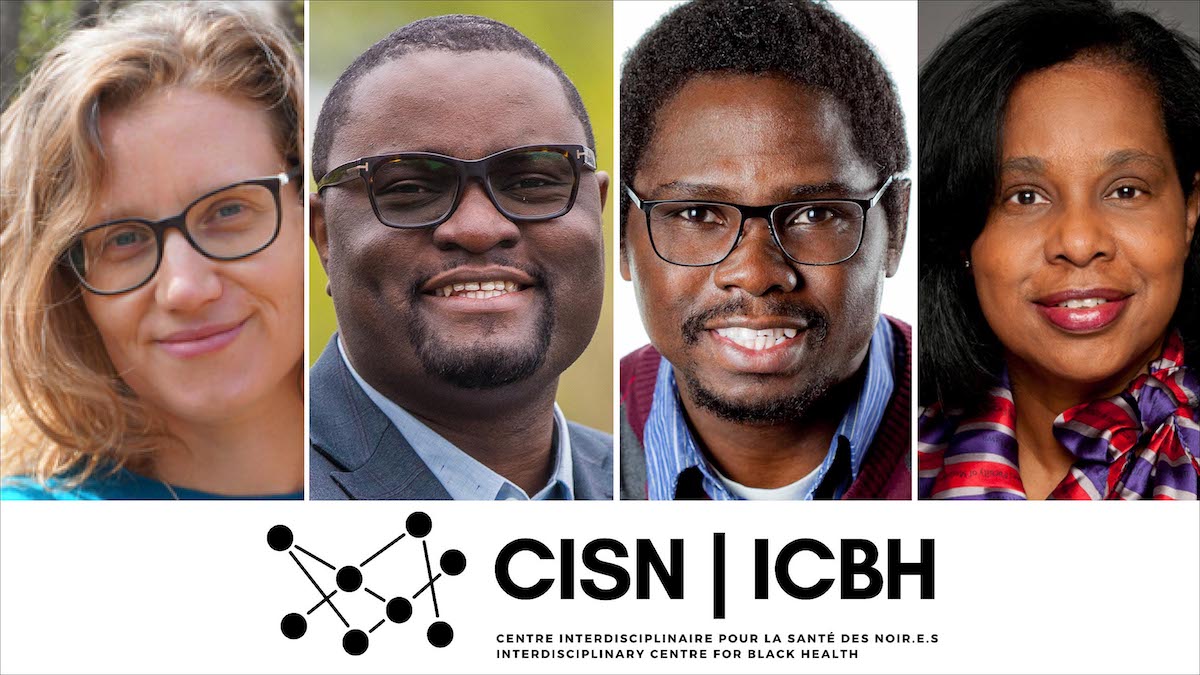

Alongside Cénat, the leadership committee of the ICBH consists of Dr. Sharon Whiting, vice-dean (faculty affairs) of the Faculty of Medicine; Chibuike Udenigwe of the Faculty of Health Sciences; and Professor Emmanuelle Bernheim of the Faculty of Law. They’ve also partnered with University of Ottawa affiliated hospitals, such as CHEO and The Ottawa Hospital.

“There are inextricable links between physical and mental health,” added Cénat. “A person who experiences racial discrimination and develops depression is also prone to experience much stress and can develop diabetes, high blood pressure and, later, kidney problems.” Bringing in the expertise of different faculties gives the centre the multidisciplinary base that allows for well-rounded research on this complex issue.

The ICBH will also focus much of its attention on developing guidelines for hospital and health centre practices concerning Black communities. Training professionals on the centre’s findings and guidelines will allow for more effective care.

“I look forward to participating in the activities of this centre, which will create more opportunities for practitioners in this area of research, as many gaps still need to be addressed,” said Whiting. “Culturally-sensitive care best serves patients and their loved ones, and it can be improved by increasing representation of members from the Black community within the ranks of physicians, medical academic staff and learners.”

With key efforts being focused on Black Canadians, researchers are hopeful the centre’s progress and findings will benefit others, as well.

“We’re definitely benefitting from a situation that favours these research synergies,” said Cénat. “We’re part of an overall environment where the progress we make in Black communities will also be useful to all other communities, including the Indigenous community.”