Outside, a heavy fog cloaked Ottawa’s autumn colours. But inside the Infinity Convention Centre in the city’s Hunt Club community, there was no dearth of colours as members of the local Bengali Hindu community celebrated the annual Durga Puja festival.

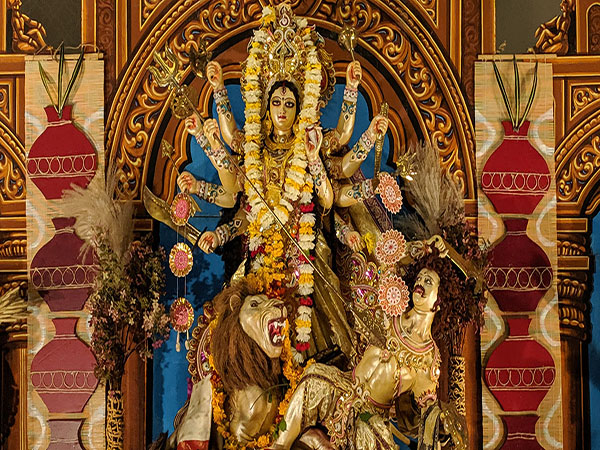

Against the south wall of the centre’s main hall stood a life-size idol of the Hindu Goddess Durga, adorned with yellow, white and red garlands, a golden saree and sparkling ornaments. Astride a lion, each of the goddess’s ten hands held the replica of a divine weapon.

At her feet lay the demon king Mahishasura, slain by the goddess in keeping with the ancient story at the heart of Hinduism. On each side of Durga were smaller idols of her four children — the elephant-headed Ganesha, symbol of luck and intelligence; the goddess of wealth, Laxmi; the goddess of knowledge and music, Saraswati; and the warrior god, Kartikeya.

Steps away from the elaborate altar, Devalina Nanda Talapatra and her friends — mostly dressed in ornate sarees and matching jewelry — were chatting away.

“I am missing home, missing India, missing family,” said Talapatra. It was her first Durga Puja in Ottawa, away from her home in India.

Yet Talapatra said she was thankful that her Ottawa friends were with her to hang out and share fond childhood memories.

“What I thought I would not get during the puja, that’s being fulfilled at least,” she said in Bengali.

Like Talapatra, people in the Bengali diaspora often come to the puja mandap — a hall or pavilion where the idols are placed temporarily during the festival — to connect to their homeland, whether in Bangladesh or the neighbouring Indian province of West Bengal.

Anindya Choudhury, president of Deshantari, a non-profit organization that has been organizing the festival in Ottawa for 40 years, explained what the puja means for the Bengali diaspora.

“We get a piece of our homeland during these four days or three days of celebration,” Choudhury said.

This year, the Durga Puja festival was celebrated in Ottawa from Oct. 15-17. But in India and Bangladesh, the nine-day festival started right after Mahalaya, which fell on Oct. 6 this year. According to Hindu mythology, several chief Hindu deities created Durga on the day of Mahalaya to vanquish the demon king Mahishasura, who was terrorizing earthlings. The battle between the two lasted for nine days ending with the goddess’ victory on the 10th day, called the Vijayadashami.

The killing of Mahishasura by Durga signies the victory of good over evil. [Photo @ Tamanna Khan]

But this year’s celebration of Durga’s legendary victory was marred by real-world violence. On Oct. 13, a mob in Bangladesh razed several Hindu temples in Chandpur, about 100 kilometres from Dhaka, the country’s capital. Officials said the attack was triggered by a Facebook post that claimed that the Muslim holy book Quran had been defamed at a puja pavilion.

In response, Islamist extremists carried out attacks in different parts of the country for days, not only destroying Hindu temples and puja pavilions, but also torching and looting houses and businesses of the Hindu community. Seven people, including three Hindu men, died in the violence, while many others lost their homes or livelihoods.

Ottawa resident Apurba Das said the disturbing incidents happening 10,000 kilometres away in his homeland overshadowed the local Durga Puja festival.

Das, who emigrated to Canada in 1997, said he’s concerned about the safety of his parents, siblings and extended family in Bangladesh.

“When I close my eyes, I see Bangladesh. But I am scared to go there. Then where should I go?”

Apurba Das, an ottawa member of the bengali Hindu community

Reminiscing about celebrating the festival harmoniously with Muslim friends in his childhood, he said he is now worried about the changes taking place in that country.

“Today you are cleansing minorities, but tomorrow the progressive people — like those in acting or media — they will be the target, and then one day this will be like Afghanistan,” he said, expressing his fear that extremism will engulf the country of his birth.

Because of personal circumstances, Das did not attend Ottawa’s puja celebration this year. But when he has gone, Das said he does not fully experience memories home at Deshantari’s puja programming, which is organized mostly around traditions from West Bengal rather than Bangladesh.

He said he does not feel part of West Bengal’s Bengali-speaking community.

The question of belonging frustrates him, Das said.

“When I close my eyes, I see Bangladesh. But I am scared to go there. Then where should I go?” he asked.

Still, Das said he feels hopeful when he sees everyone, irrespective of their religion, came out in the streets to protest violence and express solidarity with Bangladesh’s minority communities.

Various social and cultural groups from the Bangladeshi diaspora in different Canadian cities from Calgary to Montreal have been protesting the recent attacks virtually and in-person.

The Bangladeshi Canadian Hindus held a protest rally at Queen’s Park in Toronto on Oct. 25.

“The joy of worship has faded with the news of violent attacks on Hindus in Bangladesh,” organizers stated in a press release announcing the protest.