Dale Johannsen was devastated by the stroke she suffered in 1998.

“I could not speak a single word and was told I would never walk again,” said the retired city of Ottawa employee who lives in Chelsea, Quebec.

The key to her recovery was to get moving, literally. Johannsen said that during her rehabilitation period, she watched videos in her basement with her daughter and that they shared one rule. “You could not watch the videos unless you were on the bike or the treadmill,” she joked.

That was then. Today the Élisabeth Bruyère Hospital is using virtual reality (VR) games and videos paired with stationary bikes to motivate stroke survivors through rehabilitation. “These tools give you more incentive, where you can also track how much improvement you are making,” Johannsen says.

One of the main barriers in stroke therapy is motivating patients to repeat exercises so the brain can rewire. Nevertheless, new research is shaping stroke therapy practises to rely heavily on repetition and VR is one tool, says Dr. Lisa Sheehy, a researcher at the hospital. From soccer, motorcycle games and obstacle courses, patients use VR to improve balance, reach and bending impairments.

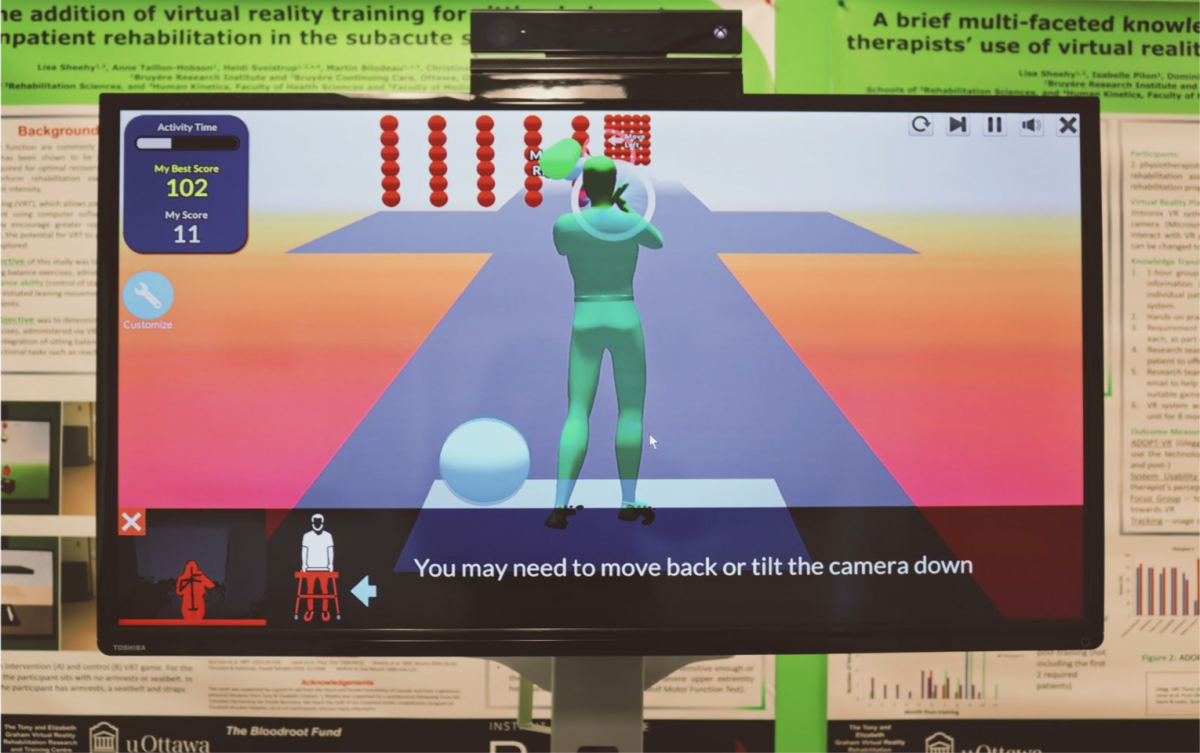

The VR games are non-immersive and patients do not use a headset as it may cause dizziness. An Xbox Kinect2 infrared camera is coupled with a software called Jintronix and tracks the user’s movement. “Most stroke patients can’t hold a controller necessarily, so an infrared camera finds your limbs and joints to follow your movements,” Sheehy said.

Out-patients in the stroke rehabilitation program have been using VR games for several years but in-patients started using the technology this fall and therapists are seeing results.

“You might get 300 steps in a session of VR whereas, without VR you might get 10 or 50,” Sheehy says. She says when patients are engaged and having fun they are motivated to work harder. For example, there was one man who could only stand for 30 seconds, and he did a game for three minutes, Sheehy says.

Virtual reality gaming technology is available for stroke survivors to use at home but must be installed by a clinical therapist. Sheehy continues to train more therapists to facilitate VR therapy beyond the hospital.

If patients don’t like VR, they can cycle across the world from Italy’s pathways, Greece’s beaches or through their hometown with a stationary bike and Motiview’s video technology. On the TV display, there are 40 countries to visit with more than 1,800 videos and a music library to enhance the experience. “Before you know it their time on the bike is over, they pedalled for 15 to 20 minutes with their paretic leg being assisted. They don’t want to stop. It’s like I want to see the beach I used to walk my dog,” says Dr. Dan McEwen, director of market development for Motitech Canada which has an office in Ottawa.

The Norwegian-designed technology is primarily targeting dementia patients but there are solutions for stroke patients.

“Some bikes have a motor that helps drive the paretic arm or leg forward while patients watch the videos,” said McEwen. Nearly one in three patients also get aphasia — a word binding difficulty- according to the Aphasia Institute. Watching videos helps patients recall memories and they have conversations about them. “As the body moves, it’s increasing blood flow to the brain allowing patients to access different areas to have conversations and practise speech,” McEwen says. Motitech is focused on clinics and hospitals for now but sees a potential avenue for home-based therapies in the near future.

Every stroke is different which means the therapy differs as well, says Johannsen. Despite being told she would never walk again, Johannsen now leads stroke survivor therapy groups in Ottawa.

She says that many patients suffer from emotional strain to be accepted back in the community and new technology is one solution. “Anything that motivates you, so much of the world is technology, I could see that being very suitable for a lot of people,” she says.