You’re holding your phone, watching an Instagram live and you can’t help but smile at the video on your screen. Comments saying, ‘What a good boy’ and clusters of heart emojis pop up at the bottom of your screen as viewers engage with the content.

You hear crunching noises as the black Mountain Dog enjoys a treat after successfully waving to his virtual viewers on command. The dog’s owner scratches the fluffy fur around his ears: “Say goodbye to everybody! Say have a good day! We hope you have a good time in your online classes… or however you’re studying. Murphy hopes you’re having a good day today.”

Carleton University’s therapy dog program traditionally offers students access to “pawsitive” support in person on campus, but during the COVID-19 pandemic, all canine outreach will occur online this year.

The program features a team of 10 dedicated dogs and their helpful handlers. Eight new dogs are eager to begin their training, which would bring the program’s number of pooch participants to 18 if all dogs pass the required tests, according to program director Shannon Noonan.

In its new virtual format, the therapy dogs are made available during live video sessions on Wednesday afternoons, via Instagram Live (@cutherapydog). The videos are then stored for viewers to watch at their own convenience on IGTV. The 10-minute appearances range from interactive trick sessions to outdoor adventures like “Nature walkies with Murphy.”

For many Carleton students, the therapy dog program is a valuable mental health support.

“Especially in my first year, I found that I just really missed my dog and I hadn’t realized just how much that would affect me,” said third-year Global and International Studies student Gillian Cook. “Being able to (visit with the therapy dogs) once, twice, even four times a week really helped my mental health and gave me that sense of familiarity.”

Although Cook wishes she could visit with the dogs in person, she says: “Carleton’s doing a great job at adapting to the pandemic. … The fact that they’re still continuing to offer this support and they’re frequently posting on the Instagram page and doing live videos shows they’re doing the best they can under these circumstances.”

Beyond providing comfort and stress-relief, the program’s in-person therapy dog sessions created a sense of community and connection its virtual format is not, said Cook.

“Something I loved about the in-person sessions was that we would talk with other students and I even made a few friends that way,” said Cook.

However, “even if you attend the virtual sessions live, there’s a degree of interaction that you can’t get because the comments are mostly (focused on the dog) than engaging with other students,” she added.

As a solution to this lack of student connection in the program’s new virtual format, Cook proposes monthly therapy dog video sessions over Zoom, which would provide students with the opportunity to engage with one another as well as the dog.

Although the details are not yet hashed out, Noonan says they will consider implementing these Zoom events later this year.

During the therapy dogs’ in-person “office hours” last year, each dog saw between five and 30 students per hour-long session. In this new virtual format, the videos generally rack up between 300 and 800 views, as students can view the recorded sessions at any time after it airs live.

However, the impact of these virtual therapy dog sessions is not just limited to students living in Ottawa. International students, alumni and even students’ parents have been watching these videos.

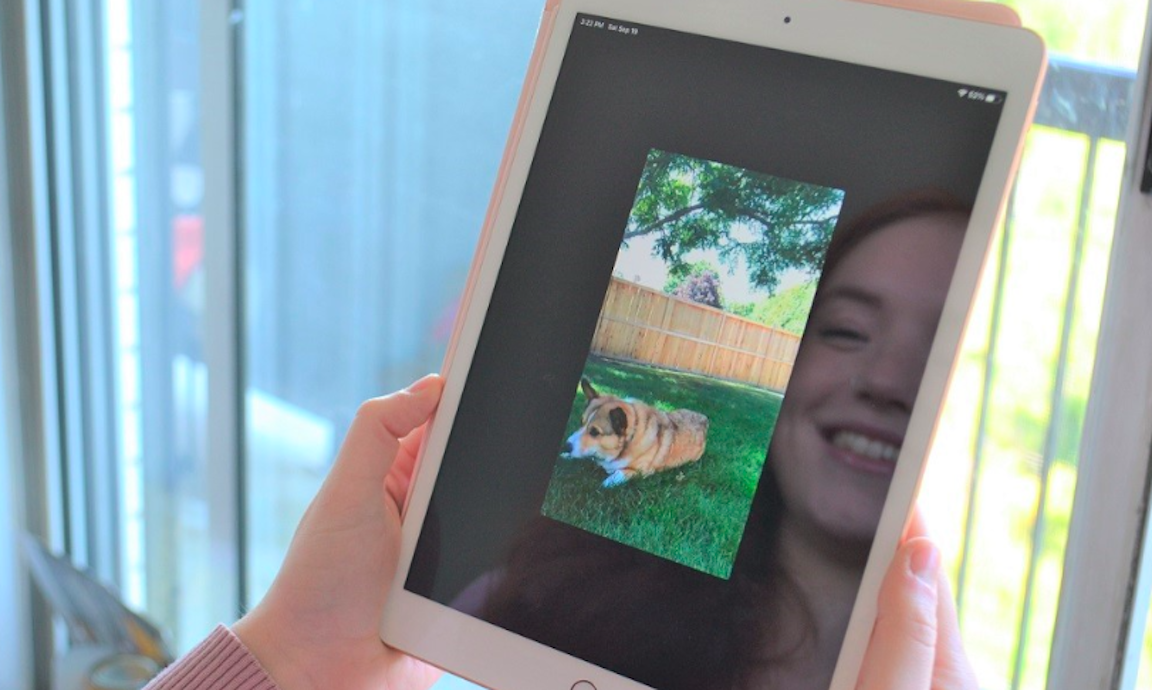

Tracy Saxton, handler of a Corgi therapy dog named Moose, has received an influx of direct messages to Moose’s Instagram account as participants share their gratitude for the program.

“It’s hard when you’re doing it virtually because in person you’re getting that immediate response and you can see that the students are benefitting from the sessions,” said Saxton. “But when you’re doing it virtually, it’s just kind of you, your dog and the phone. Getting messages from students after the fact and hearing that this is helping them … continues to motivate me to want to participate in this program.”

The online format might also help remove barriers to accessing the therapy dog program, such as conflicting classes with in-person session times, anxiety triggered by crowds or challenges with accessibility throughout campus, said Saxton.

In previous years of the therapy dog program, the opportunity for some puppy playtime was one of its biggest draws.

“It gave them an opportunity to pet and cuddle a dog, and even though it wasn’t theirs, it still gave them that warm and fuzzy feeling that they were missing from their home pet,” said Saxton.

“I will definitely miss having that contact and it’ll be an adjustment,” said Cook. “But I’m really happy that they’re still doing something virtually and now I can even watch the dogs’ office hours on my own time.”

The University of Ottawa, which runs a therapy dog program similar to Carleton’s, has also discontinued its on-campus sessions for the remainder of the school year, offering interactive Zoom calls with their team of four pups.

Similarly, Ottawa Therapy Dogs has put its in-person sessions on pause until further notice. Instead, the program has been posting short videos to its YouTube channel, OttawaTherapyDogs, more regularly since the pandemic began.

With instant access to the therapy dogs whenever she needs them, Cook said she hopes that when in-person sessions eventually resume, the program will continue offering its virtual format.

“Murphy definitely misses his visits to campus, as well,” said Allie Davidson, Mountain Dog Murphy’s handler.

“While all the online stuff is working pretty well, I don’t think it will ever compare to the same thing, which is my dog giving a student a cuddle. And I can’t wait to be able to get back to do that with students once we’re all back on campus.”