Forest fire smoke from Northwest Ontario moved into the rest of the province this past week, resulting in hazy conditions and poor air quality and it’s likely to become the new normal.

Experts say we must learn to live with wildfires and adjust our existing infrastructure to mitigate the impact on communities.

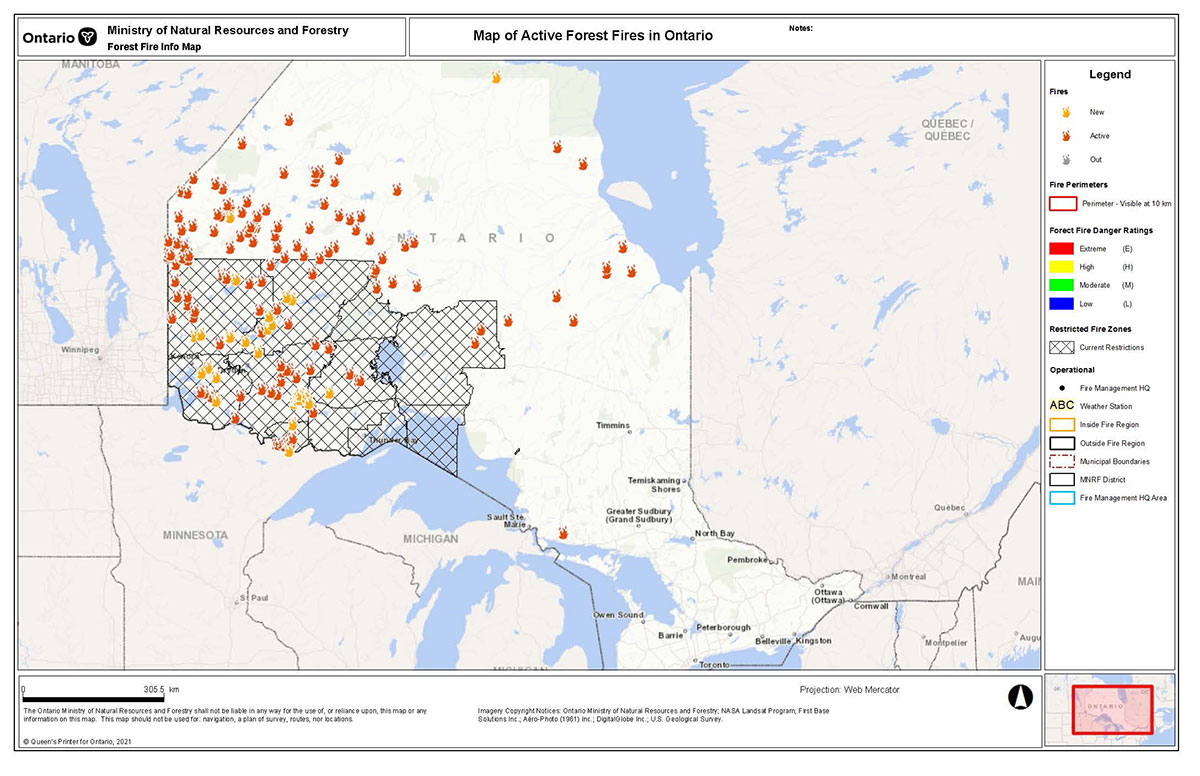

There have been 968 forest fires so far this year, nearly double the 10-year average of 520, according to the Ontario forest fire information page. There are 154 active wildfires in Ontario, most in the northwest.

The Ontario Ministry of Northern Development, Mines, Natural Resources and Forestry attributes the fires to unusually hot and dry weather conditions, not seen in close to 50 years in the region.

“Since weather conditions closely dictate fire behaviour, this dry season, as well as lightning events with minimal rainfall, is a significant factor for the high number of fires we’ve seen across northern Ontario,” says Shayne McCool, information officer for Aviation, Forest Fire and Emergency Services (AFFES), in an email statement.

Environment Canada has issued a series of air quality statements recently because of smoke moving into parts of the province from the northwest.

According to Environment Canada, “wildfire smoke is a constantly-changing mixture of particles and gases which includes many chemicals that can be harmful to your health.”

They encourage people to take extra precautions to reduce exposure to smoke, such as avoiding strenuous outdoor activities.

Not only do wildfires affect air quality, but they also have the potential to affect water quality and the amount of treatment it needs.

Historically, large wildfires in Canada have occurred mostly on more remote forested landscape, says Monica Emelko, professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of Waterloo and drinking water treatment engineer. More recently, we are experiencing fires in urban environments.

“There are all sorts of concerns now around wildfires occurring in communities and on top of communities where there’s a lot of built infrastructure,” she says.

When the built environment burns, the by-products of manufactured materials have the potential to run into our water supply, in addition to the sediments, nutrients, and organic carbon from the natural landscape.

“Most utilities are not equipped to treat those materials. It doesn’t mean that we can’t treat them. It means that we’re not typically accustomed to looking for them in drinking water supplies, and so therefore we may not have invested in the infrastructure to treat something that hasn’t historically been present in our water supply,” says Emelko.

“The more [water quality] deteriorates, the more we have to pay to clean it.”

To properly respond to the impacts of wildfires on our communities, it’s important to integrate landscape management, says Emelko.

“We as Canadians, in the global north, we need to realize that we are at the forefront of these impacts of changing climate, so we have to make adjustments. And it’s just the start in Ontario,” says Emelko.

“We need to learn to live with fire.”

Francois-Nicolas Robinne, research scientist for the Canadian Forest Service at the Great Lakes Forestry Centre

One of the strategies to prevent harmful impacts of wildfires is using “fuel management” says Francois-Nicolas Robinne, research scientist for the Canadian Forest Service at the Great Lakes Forestry Centre.

This involves cutting excessive fuel and encouraging prescribed burns. Forest management teams would use fire as a tool to naturally burn the area to prevent larger, uncontrollable burns. Reducing the amount of fuel keeps our forests from burning uncontrollably and helps the natural ecological process of the forest.

“In Canada, [fire] is definitely a huge part of our forest ecosystems. What I mean by that is that our forests need to burn on a regular basis to stay healthy,” says Robinne.

The Ministry of Northern Development, Mines, Natural Resources and Forestry has imposed a restricted fire zone for most of the northwest fire region to reduce the amount of human caused fires.

The goal, they stated, is to find fires when they’re small and easier to manage and respond to fires closest to communities and infrastructure.

Ontario is receiving firefighting support from Mexico, Australia, Alberta, Québec and the Atlantic provinces.

“We need to learn to live with fire. Fires are going to keep burning and they are going to keep impacting our communities, including our water supply … that’s something we need to accept,” says Robinne.

“In Canada, [fire] is definitely a huge part of our forest ecosystems. What I mean by that is that our forests need to burn on a regular basis to stay healthy,” says Robinne.

This is arson if these fires are deliberately lit. Planned burning does not stop catastrophic wildfire under climate change conditions

The health impacts of burning are clearly articulated in the article but then it is suggested we need to expose people more regularly to pernicious smoke and fire. In other words more susceptible people, ie those with heart disease, lung disease, the young and elderly have to suffer or die. Is this is what is being suggested? I believe it is.

There are smokeless ways to manage fuel buildup. If humans and animals were meant to endure toxic smoke we would have been born with filters on our air intakes, and this does not take into account all the other living things in our environment.

Sufficient resources need to be provided early to quickly and completely extinguish these fires rather than letting them run and then being unable to control them.

Population health should come before Forestry.

“In Canada, [fire] is definitely a huge part of our forest ecosystems. What I mean by that is that our forests need to burn on a regular basis to stay healthy,” says Robinne.

This is arson if these fires are deliberately lit. Planned burning does not stop catastrophic wildfire under climate change conditions

The health impacts of burning are clearly articulated in the article but then it is suggested we need to expose people more regularly to pernicious smoke and fire. In other words more susceptible people, ie those with heart disease, lung disease, the young and elderly have to suffer or die. Is this is what is being suggested? I believe it is.

There are smokeless ways to manage fuel buildup. If humans and animals were meant to endure toxic smoke we would have been born with filters on our air intakes, and this does not take into account all the other living things in our environment.

Sufficient resources need to be provided early to quickly and completely extinguish these fires rather than letting them run and then being unable to control them.

Population health should come before Forestry.