It’s been a year since the Freedom Convoy trucks rolled out of downtown Ottawa, but the main site of the occupation — a stretch of Wellington Street in front of the Parliament Buildings — has remained closed to traffic.

Opinions on what to do with the street — opening it to cars or keeping it closed — have been at the centre of discussion for months.

City Council voted Feb. 8 to re-open Wellington to vehicles, though the change won’t happen until sometime after March 1, and likely not until after April 1.

However, Ecology Ottawa and other critics are advocating for a different vision of the iconic street fronting Canada’s national legislature — one that prioritizes the interests of pedestrians, cyclists, tourists and the environment.

Ecology Ottawa’s plan, released Jan. 24 during debates at City Hall over the future of Wellington Street, sees the historic thoroughfare as an ideal space for community development and environmentally friendly activities. The street would be open for people but closed for cars, the group says — much as Wellington Street has operated for the past year, but without the off-putting cement barriers and road closure signage.

“Returning Wellington to cars is the opposite of what we should be doing in 2023, whether in light of the climate crisis — which City Council declared in 2019 — or the pressing need for recreational places, cleaner air or safe transportation networks,” states the Ecology Ottawa plan, which was presented at a city transportation committee meeting on Jan. 26.

The past year has shown just a glimpse of what could occur if Wellington Street were to remain closed to vehicle traffic, the group told city councillors. The presentation highlighted the Play On road hockey tournament along Wellington Street last August, a “Climate March” protest in September and the overall easier, safer travelling through the area for those who commute to work by bicycle.

“Visitors — and even locals — have been enjoying the Parliamentary Precinct and the surrounding architecture in calmness and safety,” the presentation noted.

“There’s all sorts of possibilities for this stretch (of Wellington Street) to make it a lively and vibrant area,” said William van Geest, a program coordinator at Ecology Ottawa, who also delivered the Jan. 26 presentation to councillors. “What place is more important than right in front of our nation’s government buildings?”

He told Capital Current no businesses or residents would be adversely affected by closing Wellington Street to traffic, as there’s already no place to stop or park along that stretch of the road. Additionally, van Geest argued the move would increase accessibility, especially for cyclists downtown, who currently have no real connection from other downtown streets to Wellington — which is a key link between communities to the east and west of Parliament Hill.

“Far from returning it to cars, Wellington’s current state should be enhanced,” van Geest told the transportation committee. “First of all, the federal government should be pressed to produce a plan to reanimate Wellington. This stretch is full of potential, both as a place to be and a place to travel through gently, and we should take advantage of that potential.”

The push for pedestrianizing Wellington Street is echoed by Bike Ottawa. Dave Robertson, a member of the group’s board of directors, said it’s important for the city to focus on sustainable modes of transportation.

“Ottawa needs to be more livable right now,” he said. “Part of that livability is bike lanes.”

Robertson said cutting off vehicle traffic on Wellington Street would “humanize” the area and make downtown more accessible. Creating a safe and connected bike lane is a priority for Robertson and Bike Ottawa.

Notably, less than two kilometres from the west-side road closure along Wellington Street, the city is refurbishing the former Prince of Wales rail bridge and will reopen it this year as a year-round, “active transportation” crossing renamed the Chief William Commanda Bridge.

The “multi-use pathway” across the Ottawa River between Ontario and Quebec will feature a new wooden platform for use by cyclists, pedestrians and other non-vehicular modes of transportation — including cross-country skiing in the winter.

The rehabilitated bridge can be reached from the downtown core by an existing cycling route running parallel to Wellington Street and its westward extension along Sir John A. Macdonald Parkway, which the National Capital Commission has also pledged to rename as part of an Indigenous reconciliation initiative.

However, no easy way to cycle from Wellington Street to the Rideau Canal bike path exists. This is the reason many cyclists avoid downtown, as it’s neither a safe nor comfortable space on a bike.

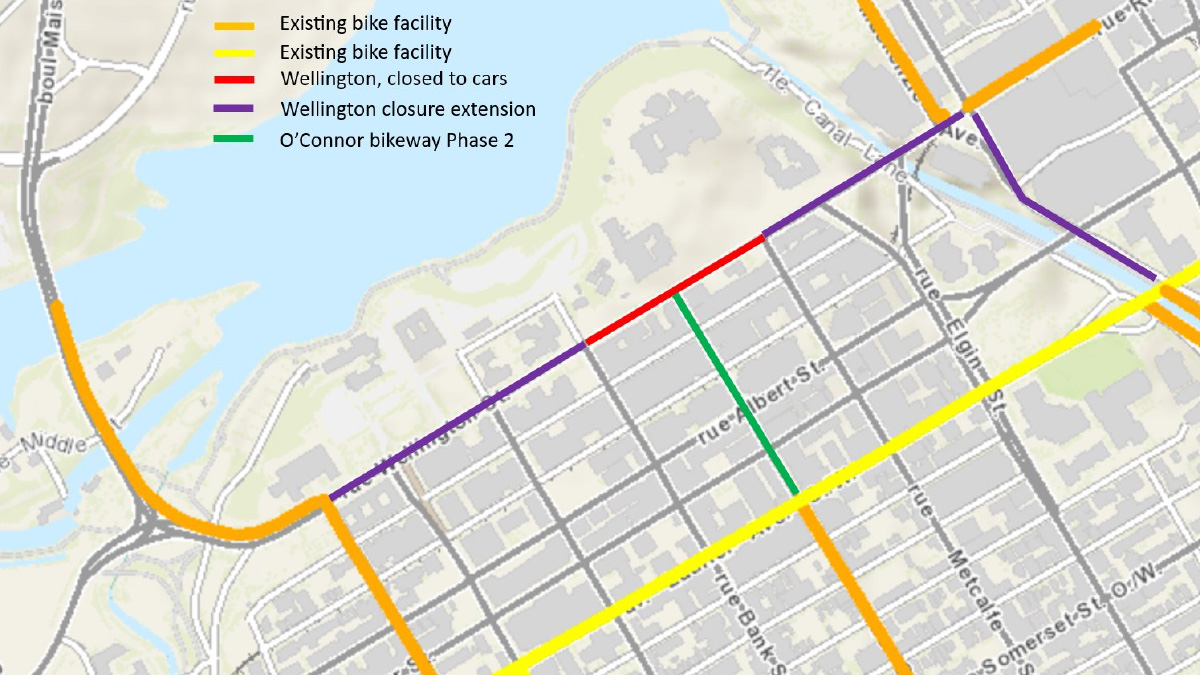

Ecology Ottawa is advocating for an increased stretch of closed road along Wellington to help connect these bike lanes and correct the missing links.

The closure, said van Geest, will help with what he calls “traffic evaporation” — a gradual reduction in vehicles as motorists take alternate routes or choose a new mode of transportation when going downtown.

During his appearance at the transportation committee meeting, van Geest argued that reopening Wellington Street to vehicle traffic runs counter to the city’s own plans for promoting active transportation and reducing vehicular emissions. Meanwhile, he added, keeping the street closed to cars and trucks is in line with Ottawa’s vision of a greener city.

In its “5 Big Moves” official plan, the city touts improved mobility as “Big Move 2.” Under the plan, Ottawa commits to reaching a point where a majority of trips by residents of the city will be carried out by 2046 using sustainable forms transportation.

Additionally, the document states that through land use policies and transportation planning, the city will “create compact, complete communities, with good walking and cycling network density and connectivity.”

A memorandum distributed to the transportation committee by Phil Landry, director of traffic services for the City of Ottawa, states that “the current closure has not had a significant negative impact to the transportation network” — meaning car traffic in the downtown core has not been adversely affected by the shutdown.

Despite these points, both the committee and full council voted to reopen Wellington Street to traffic.

The decision is a missed opportunity, says van Geest. He acknowledges that the result of council’s vote is blinding, but says Ecology Ottawa is now working towards next steps of implementing cyclist- and pedestrian-friendly traffic signals and ensuring the creation of a safe and comfortable bike lane — one concession city council has made in the name of non-polluting transportation.

Robertson said the city’s promise of a cycling lane alongside car traffic on Wellington Street is a poor consolation prize compared with Bike Ottawa and Ecology Ottawa’s preferred vision.

“People aren’t willing to risk their lives to bike up Wellington Street,” he said.

Closing a city street to traffic is hardly unheard of. Ottawa’s own Sparks Street, just one block south of Wellington, has been a pedestrian promenade for decades.

There are examples around the world of cities taking similar action.

For example, Jaime Lerner — former mayor of Curitiba, Brazil — is credited with creating one of the world’s most environmentally friendly cities in the 1970s.

Lerner led a movement to pedestrianize a main shopping street in the city in 1972 and encouraged bus transportation by making routes easily accessible and affordable.

In Canada, Montreal, Quebec City and Vancouver have also normalized pedestrian-only streets.

Eliminating traffic can encourage community building and create an enjoyable experience for tourists, say advocates of such car-free zones.

There are multiple social benefits to pedestrian-only streets, said van Geest. Having more open space in a densely populated area like downtown Ottawa is important for local residents and tourists, he said, because it allows for exercise, socialization and other activities, including improved access and openness for visitors to enjoy Parliament Hill.

Jantine Van Kregten, director of communications with Ottawa Tourism, said in an email to Capital Current, that the imminent removal of the barricades on Wellington Street and the implementation of bike lanes are welcome steps that will enhance the visitor experience of Parliament Hill.

Van Kregten said the current state of Wellington Street is not an acceptable visitor experience for a capital city. Ottawa Tourism is looking forward to working with the city to develop an appealing long-term plan for the area around Parliament Hill, she added.

Looking ahead to the addition of a bike lane on Wellington Street, Robertson said he’s hopeful the route will be wide enough to accommodate cyclists of all skill levels, going both directions.

Robertson added that he opposes the use of flex stakes — bendable markers indicating the edge of a bike lane — and instead would like to see a segregated lane with small concrete curbs, possibly painted by local artists, or even large flower planters to add visual appeal as well as a safety barrier along Wellington.

Advocates of a car-free Wellington agree that it’s disappointing a street with so much potential as a pedestrian- and cyclist-friendly zone will soon be opening to vehicles once again.

Robertson offered some thoughts on what Wellington Street could be — lined with ice sculptures in the winter months in the spirit of Winterlude, or animated by street vendors in the summer months selling things like flowers and fresh fruit.

‘Ottawa needs to be more livable right now. Part of that livability is bike lanes.’

— Dave Robertson, board member, Bike Ottawa

Another possible future scenario Robertson mentioned could see the creation of a streetcar circuit linking downtown Ottawa and downtown Gatineau via two Ottawa River bridges in the central area.

The NCC and a local group called Supporters of the Loop have been touting just such a proposed Ottawa-Gatineau “tramway” route before the Freedom Convoy occupation of downtown Ottawa last year.

In a November 2020 op-ed article in the Ottawa Citizen, NCC chief executive Tobi Nussbaum — a former Ottawa city councillor — described such initiatives as “a once-in-a-lifetime chance to be visionary in our planning and bold in our implementation.

“A Confederation Boulevard transit loop would make crossing the river easier for both Gatineau and Ottawa residents alike, providing convenient access to federal government job sites, arts and entertainment venues, restaurants and shops, and serve to deepen the ties in the region,” Nussbaum stated. “It would also offer visitors to the Capital a convenient and enjoyable way to experience the main capital attractions – from Parliament Hill to our national museums, from our stunning shorelines to our majestic monuments.”

Ottawa Centre Liberal MP Yasir Naqvi, whose riding encompasses Parliament Hill including the currently closed stretch of Wellington Street, has urged the City of Ottawa not to reopen the road to traffic pending long-term studies of the options, including measures to enhance security in the Parliamentary Precinct.

Naqvi also recently published a commentary in the Ottawa Citizen in late January, arguing that: “Wellington Street is not just a regular city road, as demonstrated by last year’s illegal occupation. The closure of the street to vehicles presents a once-in-a-generation opportunity to reimagine the area as a nationally significant, people-first space. A meeting place where Canadians can celebrate their democracy or peacefully protest their government.”

Robertson echoed the calls for more creative thinking about the future of Wellington Street: “It just takes some imagination.”